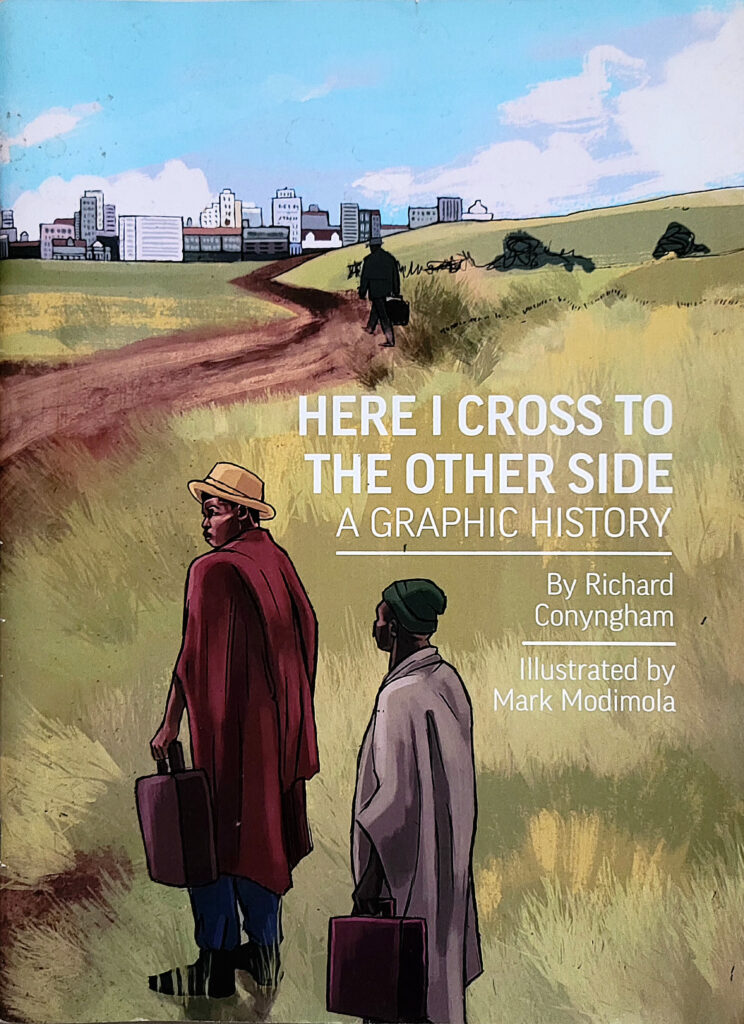

#ReadingAfrica: Three Literary Artists Celebrate African Visual Storytelling

Anthony Silverston Talks to Mark Modimola, Lisa Maria Burgess and Deena Mohamed

Every year, Catalyst Press celebrates African and African diasporic literature with #ReadingAfrica Week. This year, with the theme of Open Horizons, the conversation stretches across social media and beyond, guided by two important questions: How do we keep African literature in conversation all year, both within and beyond the continent? and How do we pursue access, inclusion, and representation across the full range of African stories and readerships?

As part of the Week, we hosted a written roundtable on what it means to visualize African stories: how illustration, art, and visual storytelling bring narratives to life and shape the way stories are shared and told. The discussion was moderated by Anthony Silverston, partner and Creative Director at Triggerfish. Joining him are three remarkable artists from across the continent: Mark Antony Modimola, a South African artist, art educator and consultant; Lisa Maria Burgess, who creates hand-stitched textile art for her bilingual children’s books; and Deena Mohamed, an Egyptian comics artist, writer and designer. Together, they bring perspectives from Southern, West, and North Africa, on how African stories are/can be reimagined.

*

This year’s theme Open Horizons invites us to think about continuity and openness in African storytelling. How can visual storytelling help “open new horizons” for how African stories are told/shared and received?

Deena Mohamed: I think it depends on how you define visual storytelling! Visual storytelling is very much an old horizon for large swathes of African storytelling, particularly if we think of the legacy of ancient Egyptian and Nubian empires, that predates a lot of what we call “comics” today. Visual storytelling encompasses a great deal of traditional and folkloric art, and has also played a role in many local art scenes across the continent.

From a more commercial perspective, Africa as a whole has been somewhat excluded from modern industries of visual storytelling, such as comics and animation, for many reasons. This doesn’t necessarily mean that visual storytelling would be a new horizon, but rather that including African artists and storytellers in these industries might expose the global market to them, allowing African artists a foothold of their own in these industries and exposing audiences around the world to African narratives.

African stories have been told visually for millennia, and visual storytelling is a fundamental part of human expression.

All mediums of art have value, whether visual or audio-visual or literary, and each have their own individual strengths and appeals. Visual storytelling in particular can reach people through the strength of image instead of relying on sound or words alone, can simplify extremely dense concepts gracefully, and above all is simply a part of human expression. This is probably a generic answer, but what I’m trying to say is: African stories have been told visually for millennia, and visual storytelling is a fundamental part of human expression. How they are shared and received today relies more on how information travels across the world, whether through specific industries, broadcasts, social media, books or print. One is a question of art, and one is a question of political and economic opportunities.

Mark Modimola: Visual storytelling can act as a universal language that allows the author and readers to identify with stories. This enables stories to form open horizons through the use of visual cues, moods set by colors and, in an African context where rhythm and sound feature as modes of language, visual storytelling has the ability to translate those dynamic, or complex ideas into easy to decipher images with a narrative behind them. Sometimes the use of onomatopoeia together with imagery gives us deeper insight into a specific narrative and infusing visual stories with the distinct African flavor.

Lisa Maria Burgess: Some African storytelling has been doing the important work of reflecting the lived experiences of Africans on the continent and abroad. I have not walked door to door and taken a census, but I’m quite sure that Africans are living in every country. Visual storytelling can reveal this reality, so we do not have to tell the stories that explain or justify this reality. In this sense, visual storytelling can open a horizon for every African story to be told. In my children’s picture books, the illustrations provide a landscape that is a stable background for the unknown narrative arc of the story. In telling a story of west African diaspora, the visuals of SnowPal Soccer/ Les copains de neige jouent au foot make the presence of an African child in a snowy North American landscape a given. The story does not need to answer the question of how this child dressed in West African fabric arrived in the snow. Because I use such textiles not only for the child’s clothes, but also for the squirrel and the tree and the rake and the shovel, because the visuals depict this reality, the story can, instead, answer the question of what happens when this child is creative and imagines a new world.

Detail from SnowPal Soccer.

Detail from SnowPal Soccer.

*

How does “visualizing stories” allow you as a storyteller/artist to circulate ideas differently from text-based literature? What freedoms or challenges come with that?

Lisa Maria Burgess: The advantage of visualizing stories is that we have more techniques than text-based literature with which to communicate.

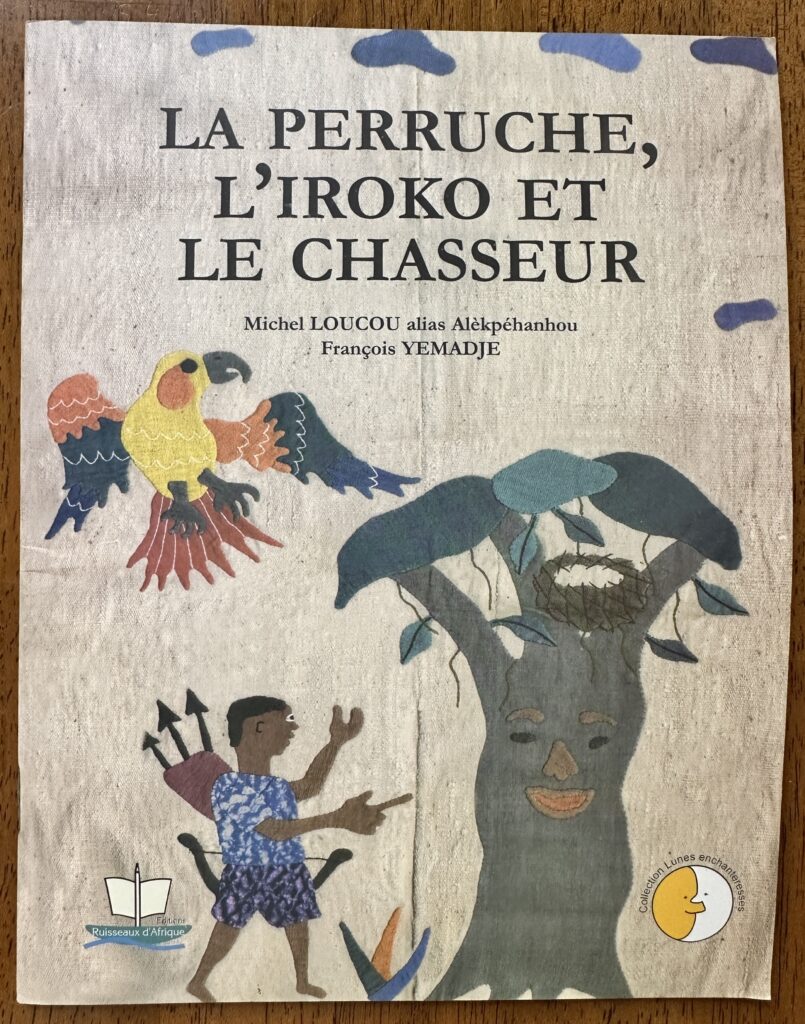

But these techniques come with their own histories. In illustrating through hand stitched appliqué, I draw on both American and Dahomean traditions. The choice of materials and techniques thus resonate in two zones. I appreciate Deena’s point that “African stories have been told visually for millennia, and visual storytelling is a fundamental part of human expression.” In West Africa, specifically in the Kingdom of Dahomey, visual storytelling was expressed for centuries through fabric (since at least back to the reign of King Agadja, 1711-1740). It was used, for example, in the form of banners to honor the gods, to commemorate success in battle, to threaten an enemy, and to sing the praises of a king. [See detail from contemporary appliqué by Yémandjè in which both umbrella and king’s hat reference a praise name story of King Houegbadja (1645-1685) regarding the fish that recognizes the net].

In North America, in the form of quilts, it has been used to commemorate family and community occasions. [See my quilt, which uses a traditional American symbol with West African textiles to celebrate Africa.].

Viewers of my illustrations may approach my art through one of these traditions, and thus be comfortable with textile visuals being connected with the stories we want to tell.

The challenge in resonating with these long traditions is that my artwork could be static, using traditional symbols that are not legible in both communities. To avoid confusion, while I use the materials and techniques, I opt for a more universal naive realism to communicate in my children’s picture books. I am interested in Mark’s idea that mood and rhythm can be expressed visually as a universal language. In choosing the winter palette for SnowPal Soccer, for example, I hoped that the colors would express peacefulness. As my visual story is read, I will be interested to learn to what extent we can achieve a universal language of mood through color or texture.

Mark Modimola: First I think of our role. We as artists are not aiming to feed people images to a story, but encourage the viewer to engage mentally with the visual cues and, in that process, form a mental image that lives with the text. The text itself urges the reader to imagine, and so we might aim to color that imagined image with visual stimuli. The purpose of the image then becomes a visual marker to imagine a particular part of the narrative. That may present the challenge of not allowing people to imagine the scene for themselves which, in our over stimulated era, might be seen as spoon-feeding our imagination.

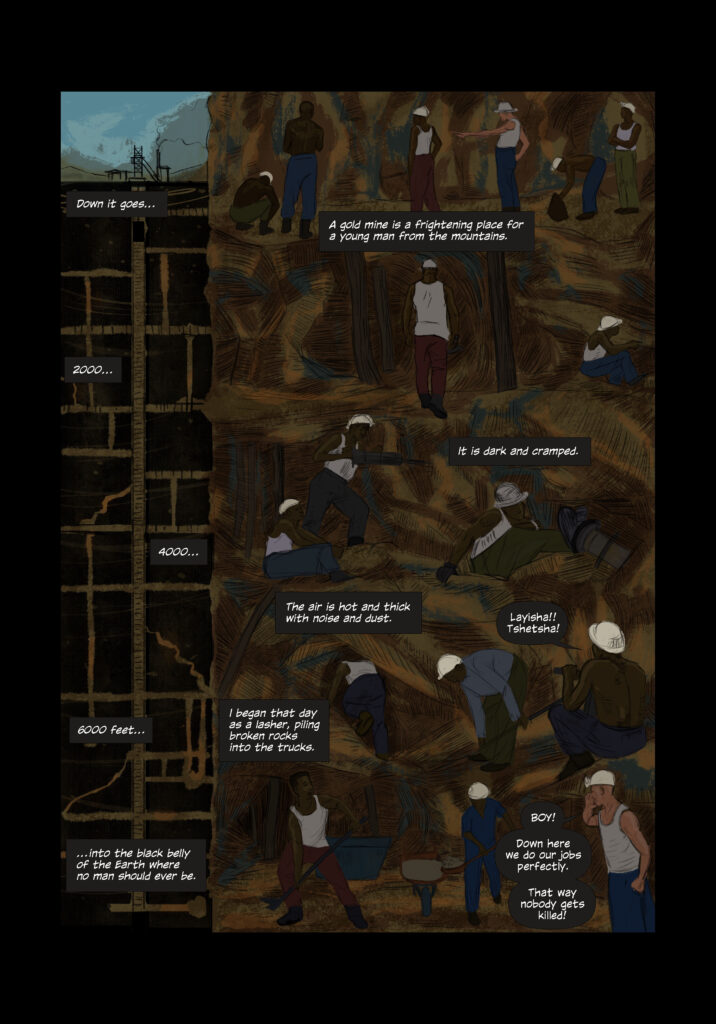

In the graphic novel, Here I Cross to the Other Side, part of the All Rises series I worked on with Richard Conyngham, we tell the story of miners during South African apartheid. There’s a scene where the miners are all working underground. Here the text on its own is compelling, with descriptions of a gold mine. The panels here are set up in a similar way to hieroglyphics, where the panels merge into the tunnels in a pace that echoes drum beats or machine knocking. What inspired the layout for me was the language used in the mines, the machines of industry in the recollection of miners and rhythm of industry. With the image, we were able to better illustrate the “nature of the mine” and the description of it being the “black belly of the earth,” a phrase that, together with the phrase “Layisha!! Tshetsha” (load-up, hurry-up), illustrate the experience of mining across all cultures.

The process of visualizing stories can be described as a form of curation, where the artist cares to encode literal text with figurative language. I like when Deena refers to the legacy of the Egyptians and Nubians’ art, which combines image and text in ancient times. These empires managed to encode their folkloric art into everyday realities through the curation of their imagery, a comic-strip like style, refined and easy to replicate, while heavily coded with elements partial to those empires’ realities, such as papyrus, chariots, and images of the afterlife.

I think the idea of visual curation as a tool for visual storytelling can be applied to Lisa Maria’s description of techniques which come with their own history. I enjoy when Lisa Maria describes her drawing on American and Dahomean traditions. In doing so, she merges two cultures and consciously curates the interplay between the cultural symbols and applications of image in order to facilitate new horizons for storytelling in the diaspora. In modern times where Africans wish to connect to each other across continents and countries, these interplays between culture become opportunities to build bridges, which relates to Deena’s point on political and economic opportunities.

These examples for me show how visual storytelling expands the scope of “languages” the story arrives in. The narratives are often coded with symbols that express more complex notions or traditions across spaces.

Deena Mohamed: This is an interesting question, because it requires you to go back and think about the basic elements that make up the medium of comics. When you’ve been working in this field for a long time, I think you seldom think about these building blocks. I really liked how Lisa Maria and Mark interpreted these, the idea of “visually curating” the storytelling built by the text in particular is interesting to me. It also reminds me of how some people consider visual storytelling to be a lesser form of literature or reading because, as Mark said, it “spoon-feeds” the imagination that text-based literature doesn’t.

But of course, the medium of comics actually serves to expand the ways that we interpret reading altogether. For example, the page Mark supplied would work with even less text. The figurative interpretation of such an image requires a literacy different to the literacy needed to read a text-based work; it works different muscles in the mind (so to speak). I have worked on many comics where there is no text at all. The circulation of ideas here means that “visual” ideas are included; ideas of color and composition and line. This is one of the freedoms of making comics. We often think of comics as the combination of text and image, but recently I’ve come to think it is closer to how artist Seth once described it: “In fact, instead of comics being a combination of drawings and literature, or film and literature, I think that comics are closer to a combination of poetry and design.”

African stories can be identified by content, but African authors can tell stories about anyone, anywhere. And in today’s world, African artists develop personal styles using a wealth of approaches.

These elements mean it is also an entirely new arsenal with which to present information and narrative. It is entirely true that while they can expand the interpretive skills of the reader, comics can indeed “spoon-feed the imagination” (I really loved this turn of phrase!) and supplement the text. This is why infographics, a form of comics, have become so invaluable in the case of dense, difficult to parse information. This is called “data visualization” and in some cases, it has also expanded into illustrated or graphic journalism. For many artists from the third world, a lot of the comics we’ve been commissioned to draw have fallen under these categories precisely for these reasons. Because people aren’t much inclined to read dense, difficult prose about our countries…but they can be drawn to reading it in an attractive visual format. Yet it would be a mistake to assume simplification is a function of comics as a medium. It is a possibility of visual storytelling, perhaps even an asset, but it is entirely dependent on the skill and intention of the artist and storyteller in question. Making easy to read, easy to understand data visualization is in fact a far more difficult skill than most people realize.

*

Illustration styles in different geographic regions can be very distinct from one another, for example European illustrations in children’s books and graphic novels can often be identified from simply looking at the illustration style. Do you think there are styles that dominate illustration and visual arts across the continent of Africa? If so, what tends to influence African visual art and what dominates it? If not, what do you notice?

Mark Modimola: Certainly, there are. Originally, we have many diverse styles across the continent which are mostly distinguished by the cultural cues and the symbology of a particular region. Sometimes styles are inspired by other forms of art such as pottery, weaving, and even farming. For example, in Ethiopia there is the distinct religious art style where figures are stylized with large eyes, bold distinct lines, and bright colored scenes. Modern Ethiopian visual styles still carry some attributes of this style while being inspired by other visual mediums.

In South Africa, we have strong mark-making styles, characterized by bold black linework that ranges from strong lines with abstract shapes to expressive organic linework, dynamic images and lively color palettes and pattern work, inspired by beadwork, weaving, and homestead painting. In Zimbabwe, I noticed artists’ linework draws inspiration from that nation’s strong heritage of sculpture.

Today, artists on the continent have found interesting ways of fusing their cultural identity to technological advancements which further grow their individual styles. I think of artists who come from printmaking and how that inspires how they process images vs. street artists vs. digital artists, each bringing a unique take to the visual arts environment in Africa.

One style that we see across the continent is broadly inspired by the culture of anime, which has permeated and blended into our visual narratives due to access to the internet. Deena Mohamed unpacks this very well in her answer, noting the three distinct comic styles. Before that, we could see hints of the American comic culture as well as music movements such as hop hop culture inspiring some of the art styles we would see. Prior to that, it may have been art moments such as cubism or surrealism.

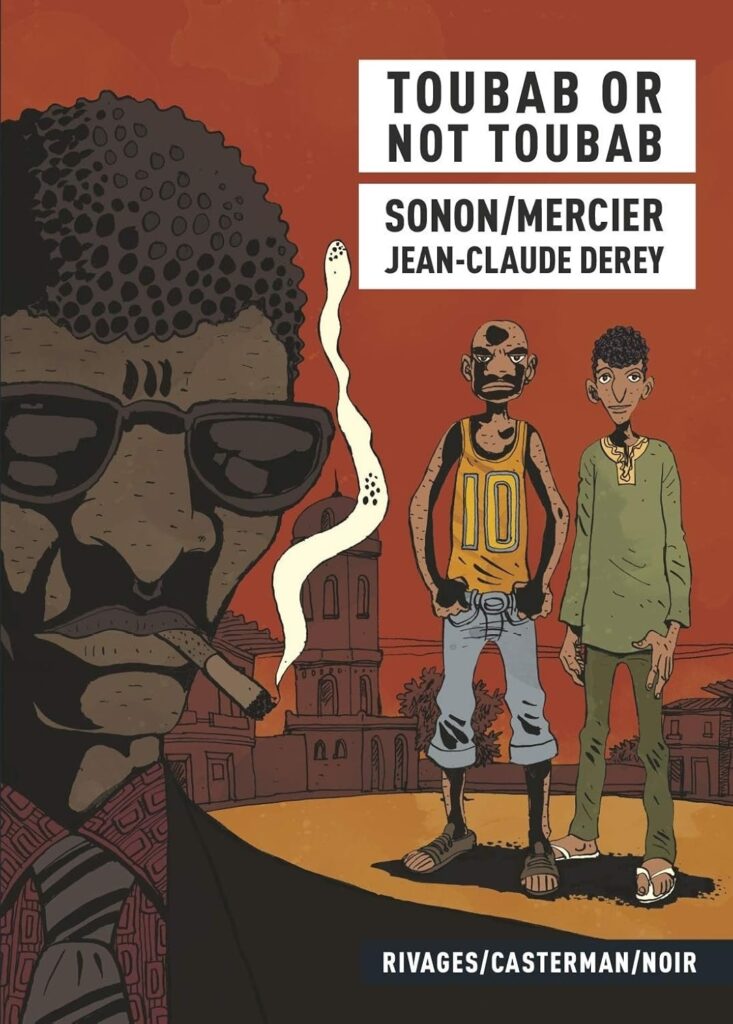

Lisa Maria Burgess: Surely every artist is looking for their own style and ways to express different stories. For example, François Yemadje uses Dahoméen applique to tell a traditional tale, while Hector Sonon uses comics (bande dessinée) to tell a contemporary story. They use techniques and develop a style for specific stories. Sonon, for example, started out as a cartoonist and uses physical disproportion to express the personalities of characters. (See interview with Sonon by Christian MISSIA Dio). For SnowPal Soccer (Feb. 2026), I use a folktale style to communicate a magical story, while in Ice Cream Time (forthcoming), I use a naive realism style to communicate a real-life story.

(See La perruche, l’iroko et le chasseur – Ruisseaux d’Afrique)

(See Hector Sonon — Wikipédia)

Furthermore, since we live in a connected world, artists can travel to conferences or workshops and meet artists from other countries, but also artists can make connections in the digital world every day. I follow Deena and Mark and Anthony online and look forward to seeing each new project even though we have never met. This connectivity gives artists a wealth of tools, but will make it increasingly difficult to categorize styles by nation or continent. Manga style, for example, is global, no longer restricted to Japan. African stories can be identified by content, but African authors can tell stories about anyone, anywhere. And in today’s world, African artists develop personal styles using a wealth of approaches.

Deena Mohamed: So I actually wrote a thesis on visual identity in Egyptian comics history! I’m a bit of a pedant on this topic in particular. To clarify this question, there are known to be three main “schools” of comics that adopt similar visual language: the American school (which includes superhero comics and underground comics), the Franco-Belgian school (which includes the “clean line” style of art) and the Japanese school of comics (which includes manga). Most other countries fall somewhere in the middle. It’s important to note that this is for modern comics in particular, it doesn’t encompass the majority of Egyptian illustrative or fine art or graphic representation in general (in which case we would have to include folkloric elements and design.)

With Egyptian comics art, it is primarily influenced by our own history of having comics created by political cartoonists, who tended towards humor and exaggerated features in the characters. It is visually closest to the Franco-Belgian style, but is a little less “beautiful” and a lot more satirical. What I really wanted was to answer the question of why you could intuit that a comic was drawn by an Egyptian artist simply by looking at it. It’s a little bit like this meme, which sums it up:

There’s actually a very long history that explains this, but I don’t know that it could be applied to other African countries. In fact, neither other North African nor Arab comics look much like Egyptian comics do. Our closest neighbor, Sudan, has a thriving comics community but they have a surprising number of artists (such as Alaa Musa and Youssef el-Amin) who work in their own unique fusion of Sudanese comics with Japanese influence, showing the impact of manga in their artistic environment. Some African comics artists have also worked close to a Franco-Belgian style, like Egypt, which may be due to both French colonialism as well as French cultural influence in promoting the 9th art in both Africa and the Middle East. And some comics artists work in more unique styles, like Lisa Maria’s, which are impacted more by traditional folklore and the visual culture of the country in question.

*

Lisa, your work uses fabric and thread (textile) to tell layered and tactile stories. How do material forms of storytelling include/invite a different kind of reader/reading experience?

Lisa Maria Burgess: Because we wear clothing made of textiles and sleep in beds covered in textiles, we are used to touching fabrics. When people read my art in a book, they immediately reach out and feel the texture even though they are actually feeling a paper page. When they see the artwork in person, one of the first reactions is to touch the fabrics. I hope that by using textiles in children’s picture books, I provide a dense performance in which the reader experiences, not only text and visuals, but also textures.

*

Deena, your graphic novel Shubeik Lubeik bridges Arabic and English worlds visually (started as an Arabic graphic novel and was later translated into English). What have you learned about translation as a visual act? (not only linguistic but also aesthetic).

Deena Mohamed: I created a whole comic about translation specifically because this felt like such an impossible task to me. I think all translation is inherently adaptation, and even translating prose text can impact how readers visualize the characters and the text. For me, the most visual element of this was the reading direction. Arabic comics are read right-to-left, while English comics are read left-to-right. Originally, I would horizontally flip the pages I was translating. This would often disrupt the flow of the story, because the reading direction is in fact an integral part of the storytelling. In Shubeik Lubeik (a story about wishes), the genies are created out of Arabic calligraphy:

This meant that I necessarily couldn’t flip any pages with genies, which would then disrupt the whole flow of the story. When it finally occurred to me to ask if I could just keep the translation right-to-left (as the manga was), it felt like I had figured out the solution to my problem. I think the very act of readers orienting their eyes to read differently helps them feel more open-minded about what they are reading. It’s the difference between reading a translation with the impatience of an owner, or with the curiosity of a visitor. I think I learned a lot through this process because I am not a professional translator but I enjoy non-professional translations. I have read fansubs and scanlations and pirated work all my life. And I think I have a lot of appreciation for a translation that allows itself to feel like a conversation.

*

Mark, how do digital tools, AI and online spaces open new horizons (AND new risks) for African art and storytelling today?

Mark Modimola: I believe digital tools such as AI present a double edged sword, where on the one hand the AI industry has been slow to invest in African models to train the AI to factor in African perspectives, which from an investment point could be a missed opportunity when accounting for Africa having the world’s youngest population, with 70% of Africans being under 30. That means there is a gap in representation and a risk of widening the gap between how Africa is seen and what Africa is. So, we need more African voices in AI and more investment in Africa so that AI works with African cultures instead of working to dilute them through stereotypes or outdated models of what Africans are.

On the other hand, AI and online spaces have created an incredible platform for the sharing, cataloging, and consumption of African art in a way which has created several revolutions in African art, changing how the rest of the world views Africa. Investment in art has been rising as a result of online spaces such as Instagram, Latitudes Online, African digital art.com and other publishing and curated online spaces. These investments have created more incentives for young Africans to see worth in investing in African art. I think these are new horizons for Africa. Storytelling is mainly accessibility, counter storytelling, and investment that reaches Africans on the ground, which can create real impact, when used responsibly.

_____________________________________

Mark Modimola

Mark Antony Modimola is a South African artist, art educator and consultant. His conceptual works across painting, digital art, printmaking and drawing aim to explore the cadence of African identity today. Reflecting on society and being through topics such as history, culture and other social contexts, he examines how we can grow as people through incorporating nature into our sense of Self. His belief that nature is an integral part of who we are as people is reflected through his works.

Some of his notable collaborations include: All Rise, the award winning 2021 South African graphic novel; The Crown Collective NGO & Jaguar for the 2021 #GiveHerACrown campaign; public art for the American Fred Hutch Cancer Research Centre and his Keyes Art Mile mural for AMEX after winning the Graphic Arts challenge in 2023. The Design Indaba 2020 Emerging Creative is a showing artist with USURPA Africa Gallery in Johannesburg. Internationally, Modimola’s work has been exhibited in the USA, Zimbabwe and Italy.

Modimola painted Africa Re-Union, a landmark artwork and artistic initiative which debuted at the FNB Art Joburg fair in 2025. His work now featuring in public and private collections globally, the young artist remains a growing and vibrant presence in the international art community.

LM Noudehou (Lisa Maria Burgess)

Lisa Maria Burgess hand-stitches textile art to illustrate her bilingual books for children. While her first language is English, she speaks Spanish and French with fluency. Lisa currently divides her time between the United States and Bénin, grew up in México, and has lived across the African continent as spouse of a United Nations staff member. She holds a doctorate in English from the University of Pennsylvania, and is married with children. One of Lisa’s books, Playing with Osito, won the New Mexico-Arizona Book Coop award for best Children’s Bilingual in 2018 (illustrated by Susan L. Roth, Barranca Press). Lisa’s SnowPal Soccer / Les Copains de Neige Jouent au Foot, which references the West African diaspora, is forthcoming with Catalyst Press (Feb. 2026). See www.lisamariaburgess.com, follow @lmbnoudehou.

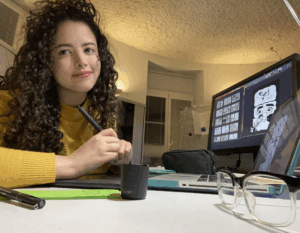

Deena Mohamed

I am an Egyptian comics artist, writer and designer. I first started making comics at eighteen, with my semi-satirical semi-sincere webcomic Qahera about a visibly Muslim Egyptian superhero that addresses social issues such as Islamophobia and misogyny. After that, I researched the history of Egyptian comics for my undergraduate thesis in graphic design, which inspired me to create Shubeik Lubeik, my graphic novel trilogy.

Shubeik Lubeik is an urban fantasy about a world where wishes are for sale. I originally self-published the first part at the Cairo Comix Festival, where it was awarded Best Graphic Novel and the Grand Prize of the Cairo Comix Festival (2017). After that, the English translation for all three parts of Shubeik Lubeik was acquired by Pantheon Books for North America and Granta for the UK, for publication as a single collected volume in Jan 2023. The Arabic trilogy was published as three separate graphic novels in Egypt by Dar El Mahrousa and all three parts are available for purchase.

When I’m not working on my own comics, I also do freelance illustrations for local and international clients such as Insider, Viacom, Google, UN Women, Harrassmap and Mada Masr. I love working on projects that involve community development, awareness and outreach (particularly editorial illustrations) as well as children’s books.

Other than that, I am largely asleep. I work and reside in Cairo. You can check the FAQ below for more information, as well as the press page for interviews I’ve done, and the events page for past talks and conferences, and the media kit for self-portrait and images of my work.

Anthony Silverston

Anthony Silverston is partner and Creative Director at Triggerfish, where he oversees a slate of projects in development and production. He directed and co-wrote Khumba, produced and wrote on Adventures in Zambezia and Seal Team and was Executive Producer on Kizazi Moto: Generation Fire (Disney+), Supa Team 4 (Netflix), and Kiya & the Kimoja Heroes (Disney, eOne and Frogbox). His graphic novel, Pearl of the Sea, co-written with Raffaella Delle Donne and Willem Samuel was recently released to critical acclaim.