Reading the Unpublished Novel My Mother Took

30 Years to Write

Caroline Scott on Realizing an Unlikely Family Dream

My grandmother read one novel in her life. She told me that fact on more than one occasion and I rather suspect that she enjoyed shocking me with it. Imagine: one single book in 88 years! The much-honored volume was Colleen McCullough’s The Thorn Birds, consumed in the wake of Richard Chamberlain doing his conflicted-man-of-the-cloth bit in the 1980s mini-series.

Dorothy enjoyed it, she said it was a good book, but didn’t feel any inclination to try another one. Her tone of voice dictated the matter closed—and none of us ever dared mention having glimpsed that copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover behind the jam jars in her pantry. When pushed, Dorothy would quote her own grandmother, who was seemingly regularly given to pronouncing that, “People who read books have dirty houses.”

How Dorothy must have despaired of the rest of us, bringing germ-harboring books into the house, and even aspiring to write our own. As a young man, her husband Kenneth had wanted to be a travel writer. In 1940 he joined the British army, and the next year set sail for the Far East, treating it very much like a journalistic assignment. I have a precious suitcase full of his letters, and the diaries that he then secretly kept for three and a half years as a prisoner of war. Grandad’s crammed-in, miniaturized handwriting at first sight communicates captivity, but on closer inspection this text is full of oceans and rivers and mountain ranges, fantasy food, character portraits and lists of the books that he means to read when he comes home. It sings and soars with escapism.

But Kenneth’s world also tilted off its pivot at this point. His identity discs were recovered next to another man’s body and he was mistakenly reported killed in action. Back in Lancashire, a memorial service was held for him, at which his father suffered heart failure. My great-grandmother then went home and put her head in the gas oven. I find it hard to imagine how my grandfather coped with it all—but, then, he didn’t always cope. My mother had childhood memories of being taken to see her father in various psychiatric hospitals. What must it have been like for Dorothy to hear the man who she’d just married screaming in the night, to have all the mirrors in the house repeatedly smashed, and to watch him being taken away to hospital again and again?

Perhaps it’s not surprising that she had no taste for drama. The passage of time, and love, do mend, though. She might have tutted when he reached for a book, but Kenneth adored Dorothy, and he got stronger for her. Lives shift. Priorities change. Along with his journalistic ambitions, Kenneth’s notebooks were put away in the suitcase that he brought back from Japan. My grandparents looked forward, not back, and they made a new life for themselves.

But the bug was in Kenneth’s blood and he passed it on. My mother grew up knowing that her father had wanted to be a writer—and, along with the red hair and the freckles, she inherited those aspirations. In my early childhood memories, Mum is at an old click-clack typewriter, there’s a smell of Tippex and cigarettes, and there are notebooks all over the floor. She would spend the next 30 years periodically polishing-up a single manuscript, cosseting it, refining, updating. As far as I’m aware, she had just one brief flurry of submitting it to publishers, got as far as an acquisition meeting, chalked up a near-miss, and then it became just a private project. She never stopped writing, but now it was a quiet, solitary pleasure.

Mum’s novel is essentially the story of a father and daughter being obliged to face up to events in their past. At its heart, it’s a book about the consequences of war. Its themes are really pretty much those that I’ve been exploring in my own work, and I wonder now if Mum too was thinking about her father as she wrote. While I make my characters walk the roads of 1920s Picardie, Mum takes hers to the Loire, where my godparents lived, and where we used to go for family holidays.

I suppose that with the handing over of her notebooks, Mum was effectively waving the white flag at the idea of one day being published.Five years ago, Mum gave me her notebooks, telling me to take anything from them that I might usefully employ. She kept a journal for each of her main characters, in which she sketched out a biography, and traits, and the distinct rhythms of their voices. She also had books in which she collected choice descriptive and dialogue phrases. Notebooks full of landscapes and interiors, idioms, cultures and clothes. I was starting to write my own novel when Mum gifted me her notebooks, I was wrapped up in my own characters and plots, but opening them afterwards, I saw so much there that was familiar; I’ve instinctively fallen into her habits, and I jackdaw the same sorts of images and expressions. Everybody tells me that I look like my mother, and sound like her, but I’ve recently realized that I write like her too.

Looking back, I suppose that with the handing over of her notebooks, Mum was effectively waving the white flag at the idea of one day being published. But if there was regret or resignation there, I didn’t pick it up. The moment seemed more positive than that; I saw kindness, and encouragement, and a sanction to invest time and hope in this activity. I felt strengthened, rather than saddened, and like Mum was passing her hope on to me. She was determined that I ought to try to make writing my career.

On the day my first novel was published, I spoke to my agent and cried down the phone. That’s really not something I normally do (my armor of English reserve is inches thick), but I missed her so desperately at that moment. I wanted her to be here, smiling with me. I wanted to place a copy of my book in her hand and to say thank you. I wanted her to read the dedication and to know that this was for her – and for Grandad.

I am planning to read my mother’s novel this winter. I know that it will hurt to hear her voice again, at first, but I also so terribly want to conjure it up. Perhaps we might work on getting it published together.

__________________________________

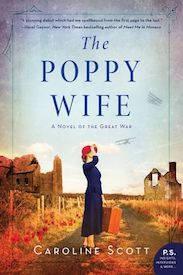

The Poppy Wife is available now via William Morrow.