On the Ambitious Beginnings of China’s Influential Soong Sisters

Jung Chang Recounts Ei-Ling Soongs' First Journey to America

When she was five years old, in 1894, Charlie Soong—wealthy Shanghai merchant and missionary—and his wife sent Ei-ling, their first child, to McTyeire School, the Methodist boarding school founded by Dr. Allen and named after Bishop McTyeire. The fact that the school’s two founders had been either hostile or arrogant to Charlie made no difference. It was the best school for girls in Shanghai—and it was American. Ei-ling herself had asked to go there. She had noticed that its pupils were given a special place to sit at Sunday services.

Even at this young age, Ei-ling showed the strong will and fascination with status that would shape her future. Her mother hesitated: the child was too young to board. Ei-ling persisted, and in the end they enrolled her for the autumn term. Grandma Ni protested tearfully. To the Chinese, one would not part with one’s young children unless one was destitute, and sending their child away from home when they had a choice was downright “cruel.” But Charlie and his wife encouraged their children to be independent, and they suppressed their feelings.

There was another indication of her later drive that would make Ei-ling one of the richest women in China: her reaction to the suitcase bought for her to take to school. For a week, as she informed her biographer Emily Hahn, she had been “at a fever heat of excitement over the preparations, the clothes and The Trunk. It was her first private, individual trunk, a beautiful black, shiny one.” But, when she saw it with her new clothes inside, “her disappointment was intense . . . The Trunk was not filled to the brim.” She “insisted upon bringing out all her winter clothes too and filling that space.”

The other thing that bothered the five-year-old was that she “had lovely teas at home; would they at the school?” She set off only after her mother packed a basket of goodies she specified, “one packet of Golland & Bowser’s butterscotch and one of bitter black chocolate.”

Finally, she was on her way by her father’s side, wearing a Scottish plaid jacket and green trousers and her hair bouncing in a pigtail. Her excitement faded when her father took leave of her; she clung to his neck sobbing and would not let go. She remembered this episode many decades later, but not how her father had broken free.

Her memories of school were chiefly of suffering. She was the only child of her age. The desks were too high and her feet could not touch the ground; her legs would go to sleep during the interminable lessons. She later confided that she “suffered horribly from that, and nobody thought of it or of remedying the situation’ “She had to find a way herself to get the blood circulating. Perhaps the worst memory was the fear at night. While the older pupils were working, she “lay in bed alone in the great dormitory upstairs, quaking with terror.” The moment of comfort came when she heard the hymn “Abide with Me,” sung by the girls after they finished their evening work and were returning to the dormitory. It signaled the end of being alone. And at the sound of the singing she would fall asleep. For the rest of her life, whenever she heard the tune, a wave of relief would engulf her.

At the McTyeire school, Ei-ling developed an even stronger character and a dependence on religion. She never told her parents about her misery. Father and Mother did not encourage moaning. This school life meant that Ei-ling’s childhood was largely a solitary one without playmates of her age. She grew introverted, even forbidding. All through her life, she made few real friends, so that when she was universally criticized, no one came to her defense.

The Soongs’ second child, Ching-ling, was three years younger, born on January 27, 1893. A delicate baby, then “a dreamy and pretty child,” “quiet and obedient,” she was her mother’s favorite. She was taught at home and not sent to McTyeire until she was 11.

Perhaps Mrs. Soong sensed Ei-ling’s distress and took pity on her fragile second daughter. Ching-ling followed her mother round, quietly thinking her own thoughts. She reacted very differently from her sister to signs of privilege. She recalled, “As a child I was taken to church on Sundays by my mother who was a devout Christian. When we arrived at church the pastor and his assistants used to drive away the poorly clad women in the front pew to give up their places to us!” This put her off missionaries, and planted the seeds for her conversion to Communism. Shy but friendly, she made a small number of friends and kept them.

Family life was disciplined and religious. Because “God wouldn’t like it,” no one was allowed to play cards—or to dance, which was deemed “devil’s doings.”The extrovert of the family was Little Sister May-ling. She went to McTyeire when she was five, because she wanted to emulate her eldest sister. Born on February 12, 1898, she was healthy, plump and spirited. In winter, her mother dressed her in a thick padded cotton jacket and trousers and she waddled about looking like a Halloween pumpkin, inviting teasing nicknames, which she did not mind a bit. Her cotton shoes, called “tiger’s heads,” had colorful long whiskers, sticking-out ears and fearsomely bulging eyes. Her hair was plaited into two pigtails tied with red strings and then rolled into round loops. The style for young girls had an unflattering name: “crab holes” which, again, did not bother her.

At McTyeire, May-ling had to walk down dark passages alone and catch up in difficult lessons. She insisted to her teachers that she found nothing difficult or intimidating. But one of them spotted her waking up in the middle of the night in fits of trembling, and saw her climbing out of bed and standing up straight beside it, reciting her lessons. The school soon sent her home. Little Sister retained her open and sunny disposition.

Family life was disciplined and religious. Because “God wouldn’t like it,” no one was allowed to play cards—or to dance, which was deemed “devil’s doings.” There were the daily family prayers and the frequent visits to church. As a child, May-ling found the family prayer sessions boring and would slip out of the room with excuses. She dreaded the long sermons in church. Ching-ling did as her mother told her to do but kept her detachment, while Ei-ling slowly but surely turned into a devout woman.

The children seem genuinely not to have resented the strictness of their parents. Rather, it inspired devotion from all six children, who looked up to their parents and felt reassured by their constancy. They were not spoilt like many other rich children, but they had their own fun. Mrs. Soong was a good pianist, and family evenings were often spent with her playing the piano and Charlie singing the songs he had picked up in America. Ei-ling would join in duets when she was home. The children were encouraged to run wild in the fields and climb trees. The siblings played among themselves. Whatever rivalry there might be between them, it was well under control. Their affectionate, close relationship extended long into their adult lives, and cemented the pillars and walls of the later famous “Soong dynasty.”

Mr. and Mrs. Soong were determined to give their children an American education. Before Ei-ling turned 13, her father had called on his old Vanderbilt friend Bill Burke and arranged for him to take her to the US. The sweet-natured Irish giant of a man had come from Macon, Georgia, a centre for the Southern Methodists, where a ladies’ college, Wesleyan, had the distinction of being the first in the world to grant degrees to women. Burke wrote to the president of the college, Colonel DuPont Guerry, who welcomed Ei-ling. When Burke took his young family back home for a short leave, he brought Ei-ling with them. At the time, America was tightening its Chinese exclusion laws to limit the number entering the country. To get round the problem, Charlie bought a Portuguese passport for Ei-ling, a practice that was not uncommon.

“It’s not right for me to dance,” the 14-year-old replied firmly. “Why?’” “Because I am a Christian and Christians do not dance,” said the unsmiling face.On a bright day in May 1904, Ei-ling, 14 years old, stood poised and reserved at the jetty on the Bund in Shanghai, with a trunk full of new Western-style clothes. She was waiting to board a tender to take her and the Burke family to the large ocean vessel, the Korea, which would carry them to the other side of the globe. She would be the first Chinese woman to be educated in America. But there was no sign of excitement, no sadness at leaving her family, nor any fear for the journey to the unknown. She parted with her father, who had accompanied her to the ship, with a restrained verbal goodbye—and without tears, unlike their parting at McTyeire years before. The teenage girl had been moulded into a paragon of self-control. Still, when the ship set sail, she burst into sobs, albeit silently in a quiet corner. Burke spotted this, and later said that this was the first and only time he saw Ei-ling betray her feelings.

Ei-ling attracted much attention. One night there was a dancing party after dinner, and the ship’s orchestra played a waltz on deck. Ei-ling passed by with the Burkes when one of the ship’s officers approached her and asked her to dance. “No, thank you, I cannot,” she shook her head sternly. The officer tried to coax her, “Well, there’s no better time to learn. Come, I’ll teach you.” “No, it’s not right for me to dance,” the 14-year-old replied firmly. “Why?’” “Because I am a Christian and Christians do not dance,” said the unsmiling face.

The Burkes traveled with her only as far as Yokohama in Japan. Mrs. Burke was dying from the typhoid that she had contracted before the journey, and her family disembarked to stay with her. Burke arranged for a couple on board to look after Ei-ling. When she went to see them, they were not in, but the cabin door was open, so she sat down to wait. When they came down the passageway, the wife said loudly, “I’m so tired of those dirty Chinamen . . . We won’t see any more for a long time, I hope.” Ei-ling rose when they came in and made a hasty excuse for having called, saying that she now wanted to go back to her cabin. She later said that the remark had seared her heart forever. It was only partially soothed by the appearance of a middle-aged American missionary, Miss Anna Lanius, who knocked on her door, introduced herself and kept Ei-ling company during the voyage. (Among other passengers on board was Jack London, going home from Korea. The 28-year-old writer of The Call of the Wild had been covering the Russo-Japanese War, and had apparently sent out more dispatches on the war than any of his fellow American correspondents.)

A heavier blow than the unpleasant remark was awaiting Ei-ling when the steamer arrived outside the Golden Gate at San Francisco on June 30, 1904. The immigration officers refused to recognize her Portuguese passport and threatened to detain her. Ei-ling lost all her poise and flared up, saying: “You cannot put me in a detention home. I am a cabin-class passenger, not from steerage.” She meant that she should not be treated the same as the coolies. In the end she was not detained, but was made to wait as a virtual prisoner on the Korea. When the ship sailed, she was moved to another vessel, and then to another.

She spent nearly three uncertain weeks on those ships. Miss Lanius stayed and moved with her, even though her own father was on his deathbed waiting for her return. Finally, through the help of the Methodist network, Ei-ling entered America. She remembered Miss Lanius warmly, but was angry about her treatment by the officials. For the remainder of the journey to Georgia, by train across the continent, she kept a gloomy silence. Burke, whose wife had died in Japan, joined Ei-ling for the trip. He was looking forward to pointing out the sights of America to her, hoping to lose some of his sorrow in her delight. He was sorely disappointed. Burke felt that he “might as well have been trying to entertain a plaster mannequin.”

That she did not bother to be polite to the man who had helped get her an American education, and who had just lost his wife, shows Ei-ling to be a willful young woman. She was still preoccupied with her bad experience more than a year later when an uncle of hers, Wen, came to Washington as a member of a Manchu government delegation. She persuaded him to let her go with them to the White House—in order to have it out with President Theodore Roosevelt. She made her complaint bluntly, and the president said he was sorry.

____________________________________

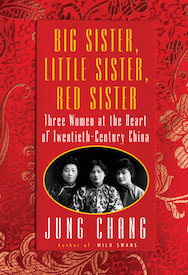

Excerpted from Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister by Jung Chang. Copyright © 2019 by Jung Chang. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.