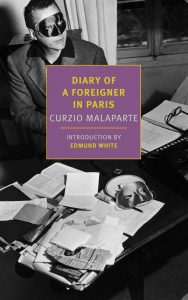

Reading the Eccentric Italian Writer Who Tried to Cover Up His Fascism

Edmund White on Curzio Malaparte's Oblong Visions of the World

On May 21st at 7:30 pm. EST Community Bookstore is hosting a virtual conversation about Curzio Malaparte’s Diary of a Foreigner in Paris between writer Gary Indiana and NYRB Classics editor Edwin Frank. You can register for free and learn more here.

*

Curzio Malaparte is a phrasemaker before anything else—sensuous phrases that stick in the imagination for a long time (“the sun’s baked-honey brilliance”). Although he fancied himself a thinker (and was quite jealous of the renown of Gide, Sartre, and Camus), his pronouncements on “the French” (“France is the last homeland of intelligence”) or on communism or existentialism or on women are often confused or repetitive or banal or wrong, whereas his recording of a sensation or a bizarre anecdote or his memory of a strange phrase is always indelible if not unerring.

In fact he is what the French call a “mythomane,” a compulsive liar who embellishes the truth, not necessarily for gain but out of an irrepressible compulsion. Anyone who has read his World War II masterpieces Kaputt orThe Skin can never forget the memorable but improbable scene when the starving Neapolitans serve to American officers a boiled young girl in mayonnaise attached to a fish tail, claiming she is a mermaid from the aquarium, or the scene when horses plunging out of a pond in northern Europe freeze in place and offer visitors a stationary merry-go-round.

Or the court of the Nazi “king” of Poland who, when he’s not sensitively playing the classical piano, leads his courtiers to the ghetto where the Germans shoot Jewish children for fun, pretending they’re rats. And where Malaparte himself offers a weeping little girl who’s starving a fat Havana cigar after she proudly refuses money. Or there’s a moment when a Fascist officer opens a pot of freshly shucked oysters and admits it’s really 40 pounds of human eyes. I’m not saying these events didn’t happen but Malaparte seems to have observed more than his share of grotesque oddities. Whether true or not, these scenes render perfectly the horrors of war.

In his Paris diary, Malaparte ends with a magnificent tableau of an aristocratic couple in Italy, the Pecci-Blunts, who are snubbed by all of their hundreds of invitees because Blunt is an ennobled American Jew and new severe racist laws have just come into effect. Unsuspected, hiding in the bushes, Malaparte and a female companion spy on the ostracized couple, who are calmly relishing the festivities—the fireworks, the live opera from La Scala, the delicate food and rare wines… Living well is certainly the best revenge. This was a beautiful scene Malaparte had first written years before but was unable to publish during the Mussolini era.

After the war, Malaparte came to Paris (which he’d last visited 15 years earlier); he was expecting a warmer reception than the one he received. He spoke and even wrote French. He was very social and dashing and had cultivated many friends during the long periods he’d lived there and kept up a French correspondence when he was in Italy. He was a famous womanizer. As is apparent from his diary, however, many Parisians shunned him and suspected him with some justification of being a Fascist “collaborator.”

When his dog Febo went missing, Malaparte searched for him desperately throughout Turin and finally found him being experimented on by a vivisectionist.In fact, he had been a working journalist for the then-Fascist newspaper the Corriere della Serra in the 1930s and had published an over-the-top article praising the Wehrmacht and had sent in many other “patriotic” reports from the front. He had also fought as a Fascist soldier in the elite Alpine forces. In Paris he emphasized that he had been exiled for five years to Lipari, an island off the northern coast of Sicily, for criticizing Hitler, and that he had been placed under house arrest in his luxurious villa in Capri and several times imprisoned for short stays in Regina Coeli in Rome, all, he claimed, for his assiduous antifascism.

In fact, in the last days of the regime he was imprisoned for having siphoned off public funds for his own use. He had been a member of the Fascist Party from the beginning and a reliable supporter of Mussolini. The real reason he was placed under house arrest was that he’d verbally attacked Italo Balbo, a transatlantic pilot who was a hero in Italy, even more popular than Mussolini himself. Malaparte had written (or at least signed) a worshipful hagiography of Balbo. When the pilot didn’t seem duly grateful for the book, Malaparte began to slander him. Malaparte was a touchy, complex man; at the end of his life he was reputedly both a staunch Catholic and a member of the Communist Party.

He certainly was eccentric. The greatest love in his life was his dog Febo. When the animal went missing, Malaparte searched for him desperately throughout Turin and finally found him being experimented on by a vivisectionist. Malaparte noticed that none of the tortured dogs was barking; the vivisectionist explained that the first step in the laboratory was to cut their vocal cords. The grief-stricken Malaparte convinced the scientist to give Febo a lethal injection and put the poor dog out of his misery.

Certainly Malaparte felt closer to animals (more innocent, less evil) than to human beings; several times in this book he sits down to bark loudly at night in the country and sets all the dogs in the neighborhood to barking antiphonally. This eccentricity is accepted in France but in Switzerland it is forbidden.

He has an infallible eye and describes “the pink, pale-green, and faded-blue varnishes of Venetian furniture,” or an evening sky that is “dark and red like the inside of a nostril.” Or he speaks of seeing the cathedral of Chartres under a “very young blue sky.” Or the sky above Chamonix as having “the cruelty the night stars have in Persian poems.” At dawn in Paris the swallows “cried softly, so as not to wake the sleepers.” Or he says that when 17th-century European diplomats described the Orient they seemed to be speaking about “tiny, fragile, transparent pieces of porcelain.”

Sometimes he comes up with a phrase right out of Ezra Pound: “She must have been beautiful, when she was beautiful.” He overhears a Frenchman speak of a German city “like the women in Italian primitivist paintings juggling the infant Jesus in one hand” while holding in the other “the model of a city or a church.”

We’re not sure what he means exactly and his descriptions don’t seem verifiable, but they can instantly be visualized. His statements, his “ideas,” are often more dubious if no less striking: we learn that “Cartesianism is the substitute for the Reformation in France.” Or that as an old man Bonnard makes “his youngest, most beautiful paintings.” Malaparte declares himself extremely Christian but notes: “If Jesus Christ hadn’t been resurrected, I wouldn’t give a damn about Catholicism.”

He has unlikely bits of knowledge, for instance that the overcivilized courtiers of Versailles called the countryside “that place where birds are raw.” He tells us that “the crueler a people is, the more intellectual it is.” He’s not the first great prose writer suspicious of culture, refinement, and deep thought. Maybe he was anti-intellectual because the French didn’t take him seriously. Or perhaps his exposure to Italian and German fascist intellectuals had convinced him there was an inverse relationship between culture and cruelty.

He’s full of opinions. He declares that the Place de la Concorde in Paris “is an idea, not a piazza; it’s a way of thinking.” He keeps worrying over Cartesianism as a dog might gnaw at a bone. One wonders if he ever studied Descartes, or if for him the name may just be shorthand for the rule of reason over instinct. Another preoccupation is the difference between two 17th-century playwrights, Racine versus Corneille. He despises women as much as he lusts after them; he tells us of a beautiful woman “full of ovaries up to her neck.”

He has a wonderful evocation of the great dressmaker, Schiaparelli: “Tall and slender, her forehead high, narrow, immense, the forehead of an Etruscan statue, the oblique eyes of an Etruscan statue, the mouth of an Etruscan statue. All the noise of the sea envelops her, and the smell of the sea follows her, and the blue and green light of the sea surrounds her, and I see again her naked foot on the sands of Forte dei Marmi, I hear again her blue and pale green voice perch atop the crest of the waves like a white gull.” The sea imagery comes from their encounter at a ritzy Tuscan sea resort, Forte dei Marmi; who knows where the Etruscan allusions originate. (She was an Italian aristocrat from Rome and the most famous couturiere of her day and did have a flat, wide face and a prominent nose.)

For such an anti-intellectual, Malaparte is extraordinarily intelligent. He was never provincial.There are lots of big names in these pages—Cocteau, the playwright Giraudoux (who’d just died), a cold, reserved Camus—but not enough friendly ones to make Malaparte feel that he’d returned to his true homeland. Although he lived another decade and began many projects, he never completed any of them, not even this diary. (This book, never revised, was published in 1966, nine years after his death.) In these pages he admits that “the least thing . . . robs me of all confidence.”

Which is hard to believe, considering how many times he’d pulled it out of the fire. In France he was out of sync with the existentialists and the Communists, the two leading cabals; in Italy he’d been eclipsed by Alberto Moravia. In America he was denounced by a knowledgeable woman who’d put together a careful dossier of all his lies; she wrote: “Truth with him is always a molecule buried in an enormous cocoon of lies ”

In an interview with the Paris Review, Moravia said, “Italians prefer beauty to truth.” That may be why Malaparte is perennially popular in his own country despite his prevarications. He certainly serves up a lot of beauty. As he himself puts it in his Paris diary, “I think about Italy, where affection flows to a name, to friendship, to beauty—never to intelligence.” For such an anti-intellectual, Malaparte is extraordinarily intelligent. He was never provincial—he knew Eastern Europe, Russia, Finland, Spain, and of course France; he could endear himself to anyone and called himself Mister Chameleon. As his brilliant biographer, Maurizio Serra, writes: “The Chameleon who knows how to play the aristocrat with aristocrats, the diplomat with diplomats, the soldier with soldiers ”

Throughout this book he seems rattled or at least he’s always taking umbrage. He makes French intellectuals responsible for Dachau. When the French keep asking him why he didn’t desert Mussolini’s forces, he chalks the question up to “coarseness.” He tells us, “I prefer real collaborators to fake resistants.” He does tell French friends a funny story. When he was 20 he was summoned to the Palazzo Venezia, Mussolini’s headquarters. After being kept waiting for hours he crosses an empty room on tiptoe and stands before Mussolini’s desk without anyone acknowledging his presence.

At last Mussolini looks at him and is astonished he’s so young. He knows every detail of Malaparte’s background. Then he says, “I’d advise you, from here on out, not to concern yourself with me. I don’t like that you’re a gossip and a malicious type.” When Malaparte asks him how he has offended him, Mussolini replies, “Two days ago, at Caffé Aragno, you told several of your friends I always wear ugly ties.” Malaparte apologizes and is dismissed. Halfway to the door he turns back and says, “You’re wearing an ugly tie today as well,” which only makes Mussolini laugh at the young man’s cheekiness.

We’re still laughing today at his outrageous remarks and discussing his singular character. What is indisputable is the beauty of his prose and the fascination of his personality.

__________________________________