Read the first reviews of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Perhaps one did not want to be loved so much as to be understood.

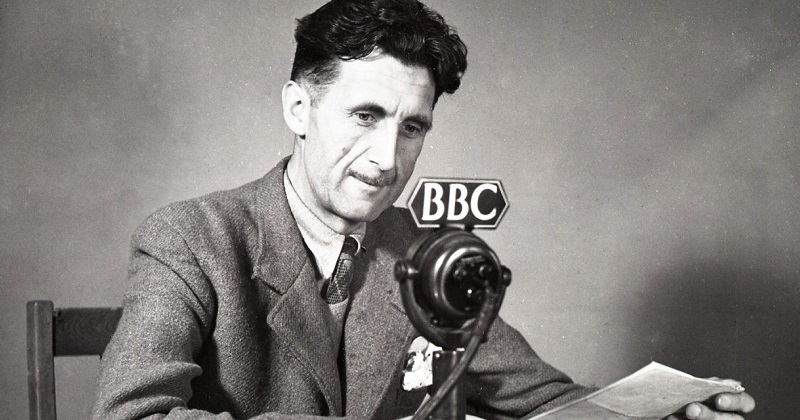

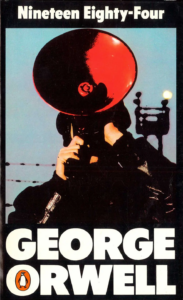

George Orwell’s dystopian masterwork, Nineteen Eighty-Four, was first published seventy-four years ago today.

Set in a totalitarian London in an imagined future where all citizens are subject to constant government surveillance and historical reeducation, Nineteen Eighty-Four tells the story of Winston Smith, a mid-level everyman at the Ministry of Truth who dreams of rebellion and who falls in love with a fellow aspiring revolutionary named Julia.

Things… do not turn out well for the pair.

Here’s a look back at some of the novel’s very first reviews.

*

“Nineteen Eighty-Four goes through the reader like an east wind, cracking the skin, opening the sores; hope has died in Mr Orwell’s wintry mind, and only pain is known. I do not think I have ever read a novel more frightening and depressing; and yet, such are the originality, the suspense, the speed of writing and withering indignation that it is impossible to put down. The faults of Orwell as a writer—monotony, nagging, the lonely schoolboy shambling down the one dispiriting track—are transformed now he rises to a large subject.

…

“These wars are mainly fought far from the great cities and their objects are to use up the excessive productiveness of the machine, and yet to get control of rare raw materials or cheap native labour. It also enables the new governing class, who are modelled on the Stalinists, to keep down the standard of living and nullify the intelligence of the masses whom they no longer pretend to have liberated. The collective oligarchy can operate securely only on a war footing. It is with this moral corruption of absolute power that Mr Orwell’s novel is concerned.

…

“In the homes of Party members a tele-screen is fitted, from which canned propaganda continually pours, and on which the pictures of Big Brother, the leader…Also by this device the Thought Police, on endless watch for Thought Crime, can observe the people night and day. What precisely Thought Crime is no one knows; but in general it is the tendency to conceive a private life secret from the State. A frown, a smile, a sigh may betray the citizen, who has forgotten, for the moment, the art of ‘reality control’ or, in Newspeak, the official language, ‘doublethink.’

…

“The duty of the satirist is to go one worse than reality; and it might be objected that Mr Orwell is too literal, that he is too oppressed by what he sees, to exceed it. In one or two incidents where he does exceed, notably in the torture scenes, he is merely melodramatic: he introduces those rather grotesque machines which used to appear in terror stories for boys. But mental terrorism is his real subject.

…

“For Mr Orwell, the most honest writer alive, hypocrisy is too dreadful for laughter: it feeds his despair.

Though the indignation of Nineteen Eighty-Four is singeing, the book does suffer from a division of purpose. Is it an account of present hysteria, is it a satire on propaganda, or a world that sees itself entirely in inhuman terms? Is Mr Orwell saying, not that there is no hope, but that there is no hope for man in the political conception of man?”

–V.S. Pritchett, The New Statesman, June 18, 1949

“Though all ‘thinking people,’ as they are still sometimes called, must by now have more than a vague idea of the dangers which mankind runs from modern techniques, George Orwell, like Aldous Huxley, feels that the more precise we are in our apprehensions the better. Huxley’s Ape and Essence was in the main a warning of the biological evils the split atom may have in store for us; Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four speaks of the psychological breaking-in process to which an up-to-date dictatorship can subject non-cooperators.

The story is brilliantly constructed and told. Winston Smith, of the Party (but not the Inner Party) kicks against the pricks, with what results we shall leave readers to find out for themselves. It has become a dreadful occasion of anguish to-day conjecturing how much torture even a saint can put up with if the end is certainly not to be a spectacular martyrdom—but ‘vaporisation.’ The less you are familiar with the idea of the agent provocateur as an instrument of oppression and rule the more you will shudder at the wiles used by the Ministry of Love in Mr. Orwell’s London of 1984, ‘chief city of Airstrip One, Oceana.’ An example of the way things are managed: Emmanuel Goldstein, the proscribed Opposition leader, is a fiction artfully sustained by the authorities to lure deviationists into giving themselves away.

It is an instructive book; there is a good deal of What Every Young Person Ought to Know—not in 1984, but 1949. Mr Orwell’s analysis of the lust for power is one of the less satisfactory contributions to our enlightenment, and he also leaves us in doubt as to how much he means by poor Smith’s ‘faith’ in the people (or ‘proles’). Smith is rather let down by the 1984 Common Man, and yet there is some insinuation that common humanity remains to be extinguished.

“In Britain 1984 A.D., no one would have suspected that Winston and Julia were capable of crimethink (dangerous thoughts) or a secret desire for ownlife (individualism). After all, Party-Member Winston Smith was one of the Ministry of Truth’s most trusted forgers; he had always flung himself heart & soul into the falsification of government statistics. And Party-Member Julia was outwardly so goodthinkful (naturally orthodox) that, after a brilliant girlhood in the Spies, she became active in the Junior Anti-Sex League and was snapped up by Pornosec, a subsection of the government Fiction Department that ground out happy-making pornography for the masses. In short, the grim, grey London Times could not have been referring to Winston and Julia when it snorted contemptuously: ‘Old-thinkers unbellyfeel Ingsoc,’ i.e., ‘Those whose ideas were formed before the Revolution cannot have a full emotional understanding of the principles of English Socialism.’

How Winston and Julia rebelled, fell in love and paid the penalty in the terroristic world of tomorrow is the thread on which Britain’s George Orwell has spun his latest and finest work of fiction. In Animal Farm, Orwell parodied the Communist system in terms of barnyard satire; but in 1984 … there is not a smile or a jest that does not add bitterness to Orwell’s utterly depressing vision of what the world may be in 35 years’ time.”

…

“Most novels about an imaginary world have as their central character, or interpreter, a man who somehow strays out of the author’s own time and finds himself in a world he never made. But Orwell, like Aldous Huxley in Brave New World, builds his nightmare of tomorrow on foundations that are firmly laid today. He needs to contemporary spokesman to explain and interpret—for the simple reason that any reader in 1949 can uneasily see his own shattered features in Winston Smith, can scent in the world of 1984 a stench that is already familiar.”

Dan Sheehan

Dan Sheehan is the author of the novel Restless Souls (Ig Publishing) and Editor-in-Chief of Book Marks.