Read on, if you dare: 20 books that are laced with sinister magic.

Dear reader: the Practical Magic soundtrack is on at full volume as I write this. I’ve got a pumpkin-scented candle going. There are decorative gourds all over the place. (Seriously, I tripped on a stray one just a minute ago.) A maple-flavored yogurt is nestling into my digestive tract right now. I’ve scheduled my weekly viewings of Hocus Pocus, and I’m planning on attending at least one (virtual) hex on the patriarchy. All that’s left is recommending a seasonally-appropriate reading list.

*

Kelly Link, Magic for Beginners

(Random House)

Kelly Link is, in my heart, the patron saint of sinister magic. The stories here suck you in. A lot of them start like normal stories: a girl thrift-shopping with her friends, for example, as in the first story. But here’s the thing. The girl is looking for a faery handbag, gifted to her by her deceased grandmother, that is said to contain a whole world. Open it the right way, and you can fall into it, if you’re not careful. The most enchanting part of this collection, though, are the moments when she turns to you, dear reader. (Is there anything scarier than being seen?) She catches you looking, catches you off guard: “I know that no one is going to believe any of this. That’s okay. If I thought you would, then I wouldn’t tell you. Promise me that you won’t believe a word.” Start here, then go on to Stranger Things Happen and meet me at Get In Trouble, which I’m savoring right now.

Carmen Maria Machado, Her Body and Other Parties

(Graywolf Press)

Do you remember that very creepy story you read as a child about the girl with the green ribbon around her neck? She always had to have it on, and you didn’t know why until the end, when she’s dying and she tells her husband he may finally know the secret. He unties the ribbon, and her head falls off. (It scarred me, too.) The first story in Carmen Maria Machado’s debut collection, “The Husband Stitch,” is a brilliant, feminist retelling of this. As though that weren’t enough to entice you, inside you will also find Law & Order SVU in an alternate universe (featuring girls with bells for eyes, an image that haunts me still) and a scary experience at a writers’ residence. (I mean, beyond the normal scariness of a writers’ residence.)

Helen Oyeyemi, Gingerbread

(Riverhead)

Honestly, all of Helen Oyeyemi’s oeuvre belongs on this list. From Mr. Fox to Boy, Snow, Bird, she puts her own spin on the idea of a fairytale. But I think perhaps the most apt embodiment of Helen Oyeyemi’s magic is Gingerbread, a witty, maddening, and wildly inventive retelling of—well, you guessed it. You’ll want to leave yourself some breadcrumbs to get out of this forest alive.

Armonía Somers, tr. Kit Maude, The Naked Woman

(Feminist Press)

Armonía Somers’ The Naked Woman is an eerie novel revived from 1950s Uruguay that tells the story of a woman who visits a sleepy village and drives its inhabitants mad. It is full of violence and dark desire. You can feel it in the prose. The sun doesn’t just set; it sinks its teeth into the earth. Fun Fact: When it was originally published, it was so salacious and violent that people didn’t believe it was written by a woman.

Yan Lianke, tr. Carlos Rojas, The Day the Sun Died

(Grove Press)

Is there anything more frightening than the image of people staggering through the streets in the dead of the night? (Think: The Walking Dead, the children under a song-spell in Hocus Pocus, a field of scarecrows in every horror movie ever?) In The Day the Sun Died, a strange thing is happening to a town’s inhabitants. They start to sleepwalk and act out their deepest desires, the things they’ve been suppressing in their waking life. More haunting than this zombie-like mass is the idea that the scariest things are the things we dream up ourselves; the horrors live inside us.

Fernanda Melchor, tr. Sophie Hughes, Hurricane Season

(New Directions)

The story starts with a dead witch. How could it not make this list? A group of children discover the body. (Ah, the ruin of innocence—a sinister magic embedded in childhood.) The village crowds together to make sense of the murder. Based on the real-life killing of a “witch,” Hurricane Season will lure you in with a smokescreen of horror and mystery and strike you with its all-too-real portrayal of corruption and human cruelty.

Lucy Corin, One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses

(McSweeney’s)

Apocalypses—you don’t say! Some of these are all-too-real right now (there’s one story in which California is burning), but there are others that really go off the rails. In one story, a soldier comes home from war, where a witch is waiting. My personal favorite is “Madman,” which begins like this: “The day I got my period, my mother and father took me to pick my madman.” And so a terrifying materialization of adolescence is born. Something Lucy Corin does that’s so haunting is give a gritty, physical form to our base fears.

N.K. Jemisin, The City We Became

(Orbit)

I have always believed New Yorkers are laced with a kind of sinister magic. In N.K. Jemisin’s latest, five New Yorkers must defend their city against an ancient evil. Here, she pulls up the concrete to expose the erasure of communities of color. The City We Became is a delightful subversion of the hatred and racism that ran rampant in Lovecraft’s work.

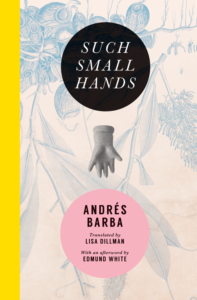

Andrés Barba, tr. Lisa Dillman, Such Small Hands

(Transit Books)

Andrés Barba’s Such Small Hands is without a doubt one of the most haunting and beautiful books I have read in a long time. It starts with a car crash that kills seven-year-old Marina’s parents and follows her to an orphanage, where she invents a sinister game that changes the lives of the other girls. The eerie plot will have you turning pages, but the delicate and particular piercing of language will give you pause. (There’s a lovely passage in which Marina first arrives at the orphanage and is looking around before she meets the others. She examines the beds with their names on them and remarks that the names are empty; they don’t have girls inside them yet.)

Laura van den Berg, The Third Hotel

(Picador)

Laura van den Berg has mastered the uncanny. In The Third Hotel, a widow goes to Havana to attend a film festival that her horror film scholar husband was supposed to be at. When she arrives, she is haunted by a man who looks exactly like her deceased husband. Reading this novel gives off the feeling of watching one of those Twilight Zone episodes. You sink into a story, and you catch the off-kilter details, and you wait for the twist.

Sue Rainsford, Follow Me to Ground

(Scribner)

Sue Rainsford’s debut novel tells the story of Ada and her father, creatures born from a mystical patch of earth called The Ground. They live peacefully at the edge of a town whose residents seek their healing powers. For particularly difficult cases, the patient is buried temporarily in the bit of The Ground in their yard that they have trained to do their bidding. The whole environment of this story is sinister. The earth comes alive but feels so unnatural at the same time. There’s one description of a healing session in which the sickness leaves the body but forms a stain on the wallpaper; there are some darkness that can’t be destroyed.

Ahmed Saadawi, Frankenstein in Baghdad

(Penguin)

Ahmed Saadwi’s novel reads like a fever dream. Sometimes funny, always horrifying, Frankenstein in Baghdad is a retelling of Frankenstein set in US-occupied Baghdad. Enter the lair of a junk dealer, who has been stitching together the body parts of bomb-blast victims to create something new: a physical manifestation of the terror we inflict on one another.

Afia Atakora, Conjure Women

(Random House)

Set in the South in the 1860s, this debut introduces us to three women: a healer, her daughter, and the daughter of her master. There is always going to be something magical about the secrets that bond women, but add to that the Civil War, the birth of an accursed child, and a superstitious town. The heart of this surreal, historical novel lives in questions of the body: the intersections of battles over women’s rights and the wars waged over controlling people of color.

Karen Russell, St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves

(Vintage)

No list like this would be compete with a Karen Russell title. Although I also highly recommend her newer collection, Orange World and her recently re-issued novella Sleep Donation, I think it’s best we start here, at St. Lucy’s. Welcome to the swamps of the Florida Everglades. Here you’ll find sleep-away camps for disordered dreamers, a boarding school for the human daughters of werewolves, and many more perfect outcasts and oddities.

Nnedi Okorafor, Who Fears Death

(Daw Books)

Before it hits HBO, you might want to read Nnedi Okorafor’s novel, about a woman surviving in post-apocalyptic Africa. There is a terrible genocide. Bloodshed fills the land. After she is raped by an enemy soldier, she gives birth to an angry baby who she names Onyesonwu, or “Who Fears Death.” As she grows, it is clear that Onye has tapped into an ancient magic—something that marks her and propels her to question the circumstances around her life. It is a dizzying, surreal tale of creation and destruction.

K-Ming Chang, Bestiary

(One World)

Family legends and stories from our homelands have a certain power over us. They haunt us more than the stories that aren’t in our blood. In Bestiary, Mother tells Daughter a story about a girl whose body was inhabited by a tiger spirit who craved children. The next morning, Daughter has a tiger tail. And that’s just the beginning of this book that spans three generations, toys with Taiwanese myth, and prods at buried desires.

Anne Serre, tr. Mark Hutchinson, The Governesses

(New Directions)

I would say you could devour this novella on a rainy afternoon, but the truth is: it will devour you. Told at an icily removed distance that gives the impression of an old fable, this is the story of three governesses that tempt the neighborhood men and eat them. (Love the black widow energy!)

Emily Temple, The Lightness

(William Morrow)

At the start of this novel, our heroine arrives at the Buddhist meditation center where her father disappeared a year ago. She enrolls herself in their “Buddhist boot camp for bad girls,” where she meets a trio of mysterious young women who are determined to unlock the secrets of levitation. The dark underbelly of this story comes in the form of female adolescence: the alluring older man who abuses his power, the obsession with the lightness of our bodies, and those twisted female friendships that make you feel loved one minute and utterly alone the next.

Marie NDiaye, tr. Jordan Stump, That Time of Year

(Two Lines Press)

In That Time of Year, a man is on vacation with his family. Then his wife and son disappear. And the weather starts to turn. And the residents of the town are acting strange. It’s like a conspiracy theory come to life. The walls of this story will close in on you. It’s a novel full of dread, in the best way.

Megan Hunter, The Harpy

(Grove Press)

You’re going to have to wait until next month for this one, but consider it an extension of this eerie October feeling. It’ll be worth the anticipation. In The Harpy, Lucy discovers her husband has been sleeping with a colleague, and they come to an agreement: she may hurt him three times. What we find here is a fascinating descent into a woman scorned. What happens when two people in a relationship no longer come to the table with the best intentions? Megan Hunter is a beautiful observer of the minutiae in a soured marriage; she has this way of picking up these little details, these tiny scraps, and wielding them in a way that pierces. Toggling between their dark present and the narrator’s lifelong fascination with the mythical figure of the harpy, the novel has a sinister, fairy-tale like quality. In this space, Megan Hunter has carved out a place for a woman between Virgin and Whore, a third kind of woman that claws at your insides long after you’ve shut the book.

Katie Yee

Katie Yee is a Brooklyn-based writer.