Ramona Quimby and the Art of Writing From a Kid's Mind

Annie Barrows on How Children Discover the World

When I made the extremely practical decision to abandon my career in publishing to become a writer, I didn’t know I wanted to write children’s books. I thought I wanted to write for adults. Accordingly, my first published work was an illustrated book about fortune-telling; my second was about opera; my third, about urban legends; my fourth, I’m not exactly sure, because right about that time, I stopped being interested in adults.

I had had some babies, you see, during this period, and suddenly, I was spending all my time with children; I read only children’s books; I talked only to children; I thought only about children. I had nothing to say to grown-ups, and most of the time, I didn’t understand what they were saying to me. Why did they want to talk about real estate when they could talk about pterodactyls? Why were they obsessed with traffic when they could be obsessed with buried treasure? Adult conversation had become incredibly dull, and adult books, duller.

It was in this spirit that I decided I would become a children’s book writer.

And in this spirit, I was totally, completely WRONG.

WRONG, WRONG, WRONG.

The problem, the wrongness, was rooted, as it usually is, in arrogance. I decided that I should become a children’s book writer because I was bored by adult books and I loved children’s books. I was going to write children’s books because it would gratify me. This is not an attitude that leads to great children’s books.

However, I didn’t know that, and I set about my new goal industriously. My first attempt was a picture book manuscript entitled Audrey and the Fire Engine, a story about Audrey, who is scared of the sound of sirens. She’s so scared of sirens that she starts dreading the noise even when she’s not hearing it. But—whew!—Audrey has a wise mother who helps her surmount her fear through several ingenious stratagems. Oh, lucky, lucky Audrey, to have such a wise mother! The end.

I thought it was pretty good. I sent it around to some writer friends and one of them connected me to a genuine children’s book author who kindly agreed to give me her opinion on the manuscript. What this kind and brilliant children’s book author said was: No. This is a book about how great Audrey’s mom is, not about Audrey. This is not a kids’ book because it’s not really about kids. This is a book that will make grown-ups feel good about themselves.

To me, the best children’s books, like the Ramona books, are the result of serious unselfishness, even humility.

I didn’t get it. It was a story about a kid, so of course it was a kids’ book! I kept reading my manuscript, trying to figure out which sentences I could change to make it better. Should I add more about Audrey? Should I put the mom in fewer scenes? I didn’t know how to fix the problem because I didn’t understand what the problem was.

Luckily for me, my oldest daughter was at this juncture beginning to move beyond picture book into books with chapters. Also luckily for me, she considered my central duty as a mother to be reading to her. So together, we embarked upon chapter books. Like every red-blooded American family, we began in the Magic Tree House and then ascended the slopes of literature until we reached Beverly Cleary and Ramona the Pest and, above all, Chapter Six, “The Baddest Witch in the World.”

I very well remember my daughter’s response to this segment of the book: complete identification with the emotional roller coaster of Ramona’s Halloween, which starts with Ramona’s passionate desire to be the “baddest” witch in the world; proceeds to her fear of her scary witch mask, happily overcome by her pride in her costume when Halloween finally arrives; moves on to a scene of liminal mayhem in the schoolyard as all the children, released from responsibility and consequences by their disguises, indulge in forbidden behavior; and then culminates in one of the most extraordinary moments of kid-understanding in children’s literature. In this scene, after tearing around the playground in her witch costume, Ramona realizes with a shock that she is, actually, unidentifiable behind her mask; her teacher, Miss Binney, truly does not know that she is speaking to Ramona. And at this, Ramona experiences a profound and profoundly human terror—is she anyone if no one knows who she is? This is followed by an even more shocking thought: What if her own mother can’t identify her? Here, we are privy to, even participating in, one of childhood’s primary fears—the mother denying her child (this is what separation anxiety is all about). Ramona wonders, “What if her mother forgot her? What if everyone in the whole world forgot her?” She removes her hard-won mask.

Illustration by Louis Darling

Illustration by Louis Darling

Right there, as I read “The Baddest Witch in the World,” I understood what the kind children’s author had been telling me. I understood what a children’s book is supposed to be. It’s writing from inside the kid’s world, inside the kid’s perspective, almost from inside the kid’s eyeballs. Beverly Cleary doesn’t tell us what Ramona’s experiencing; she doesn’t separate herself far enough from Ramona to tell us. She doesn’t say “Ramona’s mother would never forget her, but Ramona was worried that she might.” She doesn’t even insert herself into proceedings to say “Ramona thought for a moment that her mother would forget her.” Nope, Beverly Cleary gives the story to Ramona herself to experience, and she does it by withdrawing herself from the equation.

There are certainly other ways to write a good children’s book; it is possible for a narrator to be part of the tale in a non-oppressive, non-colonizing, non-grown-uppy way. But to me, the best children’s books, like the Ramona books, are the result of serious unselfishness, even humility. The author sets up the furniture, props the door open, and then covers herself with an author-cozy and disappears, leaving the entertainment to be directed, acted, and understood by the kid-characters. The wise and kindly adult who interprets the meaning of the action or, worse, teaches the befuddled youngster an improving lesson—that person is banished in great kids’ literature. The main characters, the kids, learn things on their own.

But how do you do it? How do you enter the kid-world so thoroughly? I think there are three major routes. The first is a willingness on the part of the author to be erased (which most grown-ups don’t have; they want more attention, not less); the second is a deep and serious sympathy with kids; and the third is a pretty good memory. I’m guessing Beverly Cleary has all three.

“[Beverly Cleary] knows Ramona from the inside out, and she loves and respects her.”

I’m certain she also has the fourth thing, the special extra that’s not required but is lovely: generosity of spirit. Because “The Baddest Witch in the World” doesn’t end with Ramona so fearful of loss of identity that she can’t partake of the Halloween parade she’s been anticipating for years. It ends with Ramona’s brilliant solution to the problem: She runs into her classroom, grabs a piece of paper, and writes “RAMONA Q.” Then, with nametag affixed and selfhood firmly reestablished, she pulls her mask back over her face and races out to enjoy being the baddest witch in the world in all her disruptive glory. What a great ending! How satisfactory! Are children helpless? NO! Are children resourceful? YES! Are children going to be forgotten as a punishment for donning the guises of wickedness? NO WAY! Children are going to have a great time on Halloween and overcome any problems that might arise! Plus, they are going to eat candy! What could be better?

The lesson in “The Baddest Witch in the World” for Ramona is that there is no lesson—or maybe it’s that she has the power to make herself known. But the lesson for me was profound. The lesson was this: It’s not about you. Of course, Beverly Cleary’s understanding of her own position and her mastery of what’s called “kidbrain” in industry circles didn’t stop with the baddest witch; it’s apparent in all of the books about Ramona. It’s in her glorious red galoshes and her impatience with Howie’s dullness and her dawnzer-lee-light humiliation and her response to Miss Binney’s substitute. She knows Ramona from the inside out, and she loves and respects her.

Illustration by Tracy Dockray

Illustration by Tracy Dockray

Hmm, I thought, holding Ramona the Pest on my lap while my daughter went off to the kitchen to make a potion, maybe I should forget about Audrey and her wise mom. Maybe I should try writing about something I know inside out. Like what? I thought, watching my daughter get out the food coloring (a good potion requires a lot of food coloring). All I know are seven-year-olds. Seven-year-old girls. Seven-year-old girls who want to be witches. Or paleontologists. I know a few of those. Let’s say there are two. Yeah, let’s say there are two seven-year-old girls who are very different. Let’s say their moms want them to be friends. Let’s say they don’t like each other. . . .

__________________________________

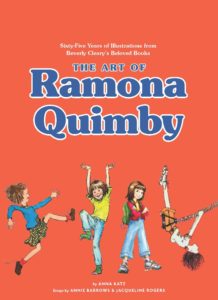

Excerpted from The Art of Ramona Quimby: Sixty-Five Years of Illustrations from Beverly Cleary’s Beloved Books, by Anna Katz, published by Chronicle Books in 2020. Lead illustration by Jacqueline Rogers.

Annie Barrows

Annie Barrows has written scads of books for children, including the New York Times bestselling chapter book series Ivy + Bean (now a series of Netflix films), as well as the Iggy series, the YA novel Nothing and the bestselling novel The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Society which was also made into a Netflix movie. She lives in Northern California.