Dayin

Nothing of their everyday was recognisable to Charu in the aftermath. Her mother had died and flied to heaven, this much she understood. But what about everybody else? When she went to hospital to become all right, they acted as if she had died to heaven and would not come back home. Now she had died and they behaved like she would come back. Her little brother had been told by so many people that Ma had gone to Thakur that he believed they too would visit heaven in an ambulance and return with her. But Charu knew her mother had been set on fire. She knew very well that when a thing is burned it is burned: it became a black powder and not even the magician who performed at the Institute gala could make it proper again.

Some days Dhrubo banged his head against the wall, as though their mother would come and give him her attention. That certainly was the case the day when the boys who walked together to school enquired whether she had become a witch.

‘She has, hasn’t she?’

‘Lives in the empty quarters next door, we know.’

Those quarters were indeed empty, for it was a period in township development when housing was in excess of posts filled.

‘Is it true, motu?’

‘Ha ha. Isn’t it, fatty?’

Dhrubo chubbied along vulnerably. They pushed his head up and he reacted with a violent swipe of the hand accompanied by a breathless sniffle.

‘Dayin! Dayin!’ the boys chanted in triumph.

‘Dayin! Dayin! Ahh ha ha, dayin!’

Tushtu, the meekest, frailest of the chanters, trailing at the back, stopped to turn towards Charu with a sly grin. She pushed him. Dhrubo whirled around to look at her as if to say, ‘What did you do that for?’ The chants tapered off.

But Dhrubo knew they would come back with twice the energy and their reputation as children of a witch would only multiply.

Charu cried quietly, less for being taunted than the force of what she had done.

‘Your mother is not a witch,’ her friend Ranu consoled her. ‘She has only died.’

‘She has not,’ replied Charu, not sure why.

She resumed walking with Ranu. Afterwards, she feared she would have dreams.

Anando had dreams. He was said to occasionally wake up screaming. But it was hard to tell with Anando nowadays. He was under the control of Thakuma and her perpetually cocked ear, and ‘Why are you asking him that?’ and ‘Why are you telling him that?’

Instead she asked Dhrubo the next day.

‘Do you have dreams?’

He still seemed annoyed with her.

‘Everyone has dreams,’ he told her, as if she was some kind of idiot.

‘Does Ma come in them?’

Dhrubo did not answer the question. He pawed the mud near the chicken-wire gate to the house, as he often did for reasons best known to himself.

‘When we give food to the crows,’ he said, ‘they take it to Ma in heaven.’

He leaned on the gate, continuing to paw the mud, concentrating on his footwork.

There were still seasons, birds and bees, and days and weeks in all their wretched assuredness. Roses took in the flower beds of the administrative gardens, their petals fell, gave up colour, dissolved into the eternity of cycles. Chitol brittled down, he cracked up, joined himself together again and again. In generations gone, he reminded himself, when every other child or mother died at birth, when the bloodline of every other family was shaped by tuberculosis, pox and plague, flood or drought, they carried on with strength and dignity.

Yet when he awoke before the first siren went off at five o’clock, he wished he could crumple up. He would look at Anando next to him, put his hand on the boy’s forehead trying to divine whether he had had dreams. His own dreams he could not talk about, dreams that were hellish self-interrogations. Could you have done anything different? his voices tore away at him. Why didn’t you? The last moments were seared into him, the first sight of his children afterwards. He marvelled at their fragility, their resilience, their trustingness. He brought himself to straighten up and face his days.

In the open backyard he applied tooth powder one tooth at a time, massaging the front and the back of each anticlockwise three times with his right index finger. Then he rinsed his mouth explosively three times. He received Shyamlal the milkman at the gate, walked to the ward market to buy vegetables from Hori. In his bath he attempted to feel, really feel, the freshness of the day as he ran the water over his body. If they were not already up, he woke the children by tickling the soles of their feet. In the garden or the front veranda, depending on the season, he had his tea and ruti or panta bhat. Before he left the house he wrapped around his neck, seasonally, a muffler or a thin cotton gamchha hung always on the left corner of the highest bar on the clothes horse. The entire point of routine is that its divisions are small and its aims achievable, defined to be so by the one who sets them. In getting from one thing to the other, merely that much, the chances of success are higher than failure, and in this way we generate the momentum for living.

Before the third siren at seven o’clock Chitol parked his bicycle alongside hundreds of others like it, his identified by a faded yellow piece of his wife’s old sari around the handlebars, which doubled as a duster. She had tied it there. These objects of her memory he sought to apprehend with the same stoic acceptance he tried to apply to his predicament in general.

Mornings he spent on the floor of the Light Machine Shop. By designation, Chitol was Chargeman B, the intermediate grade among chargemen, reporting to a foreman, and himself in charge of about a dozen skilled artisans and mistries and half a dozen khalasis. In one set of shops, the Bhombalpur Railway Workshop turned around locomotives and coaches sent in for repair or periodical overhaul, while it aimed to become capable of assembling them; in another, it manufactured a variety of parts used in this railway workshop and others. In the workshop, surrounded by grinding and milling and sawing and drilling and lathe machines, amid sounds that tremored up towards the distant corrugated-iron roofs, in light that glinted off metal and grease and skin, it was almost possible to forget the hole inside him.

At the lunch siren he made for the subsidised canteen, for in his new situation he no longer carried a tiffin – his mother had quite enough to do with the children. After his meal he went into the grounds for a stroll and a cigarette, usually with his friend Pal from the Coppersmith Shop, who kept himself reliably up to date with gossip, riddles and jokes. Thereafter, to freshen up, he took mouri from his metal canister, scattering some of the fennel seeds for the birds and squirrels to experiment with.

Unless required on the floor, the afternoon he stayed in the cabin he shared with two others. Sitting there at his desk, his tumbler full of water again, covered by light lace, Chitol often mulled over the contradiction in his circumstances. In the older times of greater casual suffering there had always been a way. When the living was joint, the place of a mother could be taken by the house at large. Out in this railway township, where men were units producing units, families were units occupying units, he had nothing to fall back on.

There had been good reasons for coming here, he frequently reiterated to himself. The new works needed men; he considered it his national duty. With the move had come better prospects, and living quarters that were available as per pay-scale entitlement. He had not a permanent home. To the village left behind generations ago there were no ties any more; and now it stood in another country. Each generation and its movements, its itinerancies. His father had worked as a scribe, a schoolteacher, a clerk at a trading firm, a manager at a ferry service, in a swathe across northern-central-eastern India, living out of homes that were never self-owned. To be the first to occupy a house meant something.

Chitol retained the faith that the township was modern, progressive, with the tacit force of nation-building behind it, and likewise that he had taken modern, progressive steps with the tacit force of nation-building behind them. He had long been guided by these principles. A young man at Independence, he had partaken of its euphoria, shed the ancient conventions that had held the people back. He believed the caste system could be undermined by jettisoning caste titles; and rather than curtail his at the neutral but bland Kumar, he had adopted, first as pen name and then as surname, this delicate, delicious, absurd, oily fish, which, he reminded the baffled Chattopadhyays in his clan, was the very first avatar of Vishnu, thus terribly auspicious. He had married for love not society, and contrary to common recommendation did not wish to remarry from compulsion. Their children he had enrolled in school as soon as they became eligible in age, their girl too. No matter that the school was not the Jesuit or the Convent, beyond the means of a Chargeman B, the Bhombalpur Boys’ and the Bhombalpur Girls’ Railway School (English Medium), in whose hot queues he and his wife had waited by turns to secure first-come-first-serve seats, were superior to the state government schools, and almost on a par with the central government schools in the township, all for an annual fee of one rupee. In short, he had, he was, he would, he will, they will, we will, somehow we will…

Animesh Kumar Chitol, whose spectacles were thick, whose hair was jet black if thinning, his mouth sweet and gentle, eyes heavy-lidded, stooped over his desk in the manner of a calm babu tackling paperwork, did not readily give the impression of a mind consumed by worry, or the literary expression that was its subsequence.

He no longer wrote with any interest in publication. Unlike his children, his own schooling had begun at home, and Bangla remained his language of deepest articulation. What he wrote nowadays were not exactly stories, nor humorous sketches. They were pockets of prose influenced by his readings, high on poetic imagery that (it was his private opinion) surfaced like bubbles and left the juice of their burst on the page.

In one of them, a man is dreaming, and in that dream a man is dreaming of an enraptured conjugal relationship with every woman he has ever been attracted to, each of whom is herself dreaming rapturously of conjugal relationships with every man she is attracted to; the series of dreams erupt one by one like fireloom, and the original man is bedazzled, blinded, wishes to break out of the dream but cannot. In another, a man faces a wall in a hexagonal room. The man, named Bawrgiyo Jaw, is possessed of a tremendous mandible, and the black tips of his spectacles loop over the tops of ears that enclose a full head of black hair. He attempts to fill the wall with the Bangla alphabet, in a way that it includes every vowel and consonant, but no matter what he means to write they end up spelling the word Jigyasa, which is the name of the mother of the man’s three children. There was nothing he could have done different. Could he?

As he embarked on another afternoon’s routine, in front of Chitol manifested Charu. He studied the girl in her crumpled pinafore stitched by the railway wives of the Mahila Samiti and tried to ascertain where this piece of writing could go. A man works with machines, one day a machine spews out a fully-made version of his child, who creeps up on him when he isn’t looking, and now the man must contend with the machine as well as the machine-made daughter. He wondered if it could be interpreted as anti-modern, or too modern. Then he heard Charu say ‘Baba’, and it hit him like cold water. He noted the collection of staff at his cabin door, the shop activity beyond, and right before him, in violation of all expectation and safety norms, his daughter.

‘What has happened?’ Chitol asked, jumping to life.

‘Nothing,’ she replied, as though weary of the question. But he could tell she was on edge.

He sprang up towards her, hoping the demonstration would scatter the audience. It also gave him the chance to close the door, although the top half of the wooden cabin was glass. In a minor slice of luck, neither Sahu nor Clemence was at his desk.

Charu looked around the cabin, so cramped compared to the huge shed with the highest roof she had ever seen. She wondered how anyone worked in this much noise. It was clear to her that she would have to answer. Yet, away from the house, where he seemed complicit in her grandmother’s monitoring, she sensed her father was not so inclined to hold her to account.

She told him, therefore, without being further pressed, leaving him to visualise.

At the edge of their school ground, an old banyan tree. She and her friend Ranu, swinging from the hanging roots, which only the boys ever did, for the primary-school playground was shared, and if any girls did, it was when no boys were around. As she swung, her hands burning from gripping the roots, she saw a group of girls pointing at her and she already knew the things they might be saying about the daughter of a flying dayin, but it did not matter to her because she was flying and those girls they were not. Back on earth she decided she would not go back with the girls into the building. She stayed behind at the tree. Even Ranu left. She walked through the bushes near the periphery, which she had never done before. She saw broken bottles, torn shoes. Horrible smell. She entered a grove of trees dark as a jungle and she heard birds shrieking. Beyond the trees a fence of thorns. A section of the fence had fallen down, and she climbed over it and hurried down a path, her heart pulsing like a caught frog as she raced downslope – leaving her books, her bag, her brother, her entire school behind. Out in the full glare of the riverbank dogs were barking, clothes were drying on the ghat, little boys were playing with marbles, running about with strings, beating along old bicycle tyres with sticks. In the distance the shape of the workshop rose above the trees. She began to walk in that direction. It was much further than she thought, but the breeze that blew over the water filled her ears and she felt she could fly all over again, get knocked about in the air like a butterfly, and the fear left her heart. She kept going until she saw a path climbing up from the bank and towards the back of the workshop compound. And … is it true that Ma has become a dayin?

‘No, it is not,’ said her father, categorically.

‘I knew it.’

Chitol considered the figure before him. For endangering herself on so many fronts she deserved a slap. For the sake of form he considered administering it. But he felt tears materialising. He hoped his spectacles concealed them, for were he to indulge himself, they would spill over and spread along the frame and smudge the glass and his cheeks transparently.

A peon came in and placed papers on the desk.

He is short, thought Charu, recently competitive about height; I can overtake him.

Her father gathered his things and put them into his cloth bag. ‘Let’s go home,’ he said. At the time-office she was excited to see the time-keeper punch him out; and in the sea of bicycles she was excited to locate his by the yellow sari.

She helped herself on to the bar, as she had become proficient at doing, and he wheeled off slowly, his light-machine legs pumping away, up the long route that skirted the artificial lake and looped around the high-officers’ mansions with their over-maintained gardens, through the residential ward of clerks people called Babupara, into their own ward, Gulab, their row of C-types, to their quarters with the precious flowering yard.

__________________________________

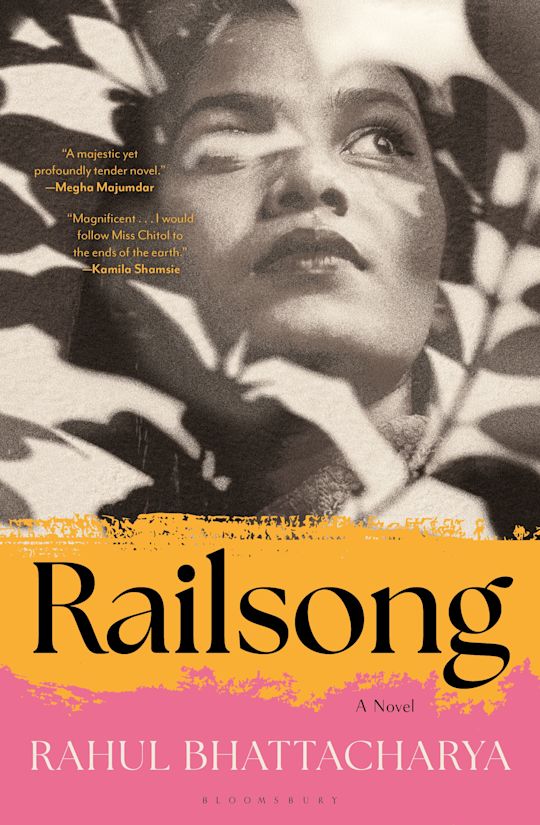

From Railsong. Used with permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2026 by Rahul Bhattacharya.