In 1972, abortion was illegal in Minnesota. One day that year—the exact day has vanished from memory—a 21-year-old man drove his terrified 16-year-old girlfriend to a women’s clinic in Minneapolis. He left her there for a pregnancy test and drove away.

I was the girlfriend. There were no home pregnancy tests back then. The boyfriend’s cowardice still rankles me, but most of all, I remember my fear, confusion, and miserable secrecy about my possible state. My imagination roamed to back-alley abortions. I had seen the results of some of those illegal procedures in grainy black-and-white photographs—the corpses of young women lying in pools of their own blood on filthy sofas and metal gurneys. I imagined myself in a grimy room with a strange man and his gleaming tray of instruments.

I had no money of my own. Had I been pregnant—it turned out I wasn’t—my boyfriend or my parents would have had to secure the funds for an abortion. I feel certain they would have, although none of them had much to spare, and the idea of my father knowing about my pregnancy sickened me. I do not think a flight to New York and the hundreds of dollars needed to pay for the procedure would have been possible, but I never would have gone through with a pregnancy. I would have broken the law.

Sixteen years later, I gave birth to my daughter, Sophie. When I pushed her out of my body, I was in a state of ecstasy I had never experienced before and have not experienced since. I am well aware that birth experiences are hugely various. That was mine. How I wanted that baby.

Legislating reproduction and curtailing reproductive rights has been and remains a hallmark of authoritarian and fascist governments.Years later, after she had finished college and was living on her own, Sophie called me. I heard in her voice that something was wrong. She made it known the problem was medical. She’s been diagnosed with a fatal illness, I thought. I braced myself. When she told me she was pregnant, I was so relieved, I laughed. She recalls my own words better than I do. “This is New York,” I said to her. “It’s your decision. If you want an abortion, you can get one.” It was very early in the pregnancy. She chose an abortion and has never regretted it.

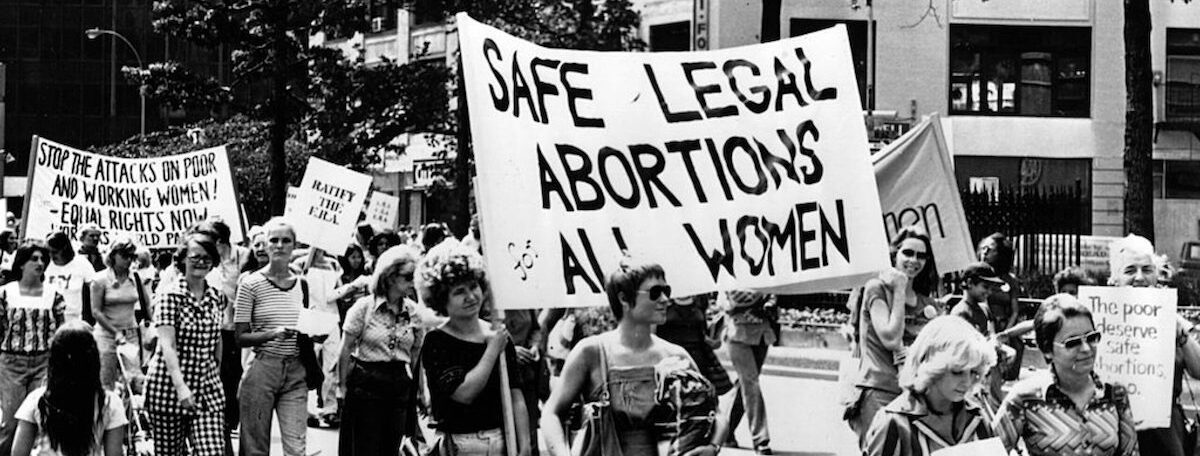

The year after my pregnancy scare, Roe v. Wade became law of the land and stood for almost 50 years. The United States Supreme Court has abolished the constitutional right to an abortion. It is time to be afraid again, and it is time to act on that fear by protesting the decision and voting out radical, anti-democratic politicians.

Legislating reproduction and curtailing reproductive rights has been and remains a hallmark of authoritarian and fascist governments. In Nazi Germany, abortion was strictly forbidden for all “Aryan” women, who had a duty to reproduce for the Reich. Special courts both in Germany and in Vichy France were authorized to issue the death penalty for illegal terminations of pregnancy. In Mussolini’s Italy providing information about contraception was a criminal offense. Abortion, already illegal in the country, was further criminalized. In Spain in 1941, Franco formally made abortion a crime against the state.

Poland’s right-wing Constitutional Court has increasingly tightened its already highly restrictive abortion laws. Late last year, anxious about breaking the law, doctors refused to remove a dead twin from a woman’s uterus. She became gravely ill, but they still refused to intervene, even though Polish law reserves the right to an abortion when the mother’s life is in danger. Not until two days after the second twin died inside her did her doctors terminate the pregnancy. On January 25th, the woman, known only as Agnieszka T., died. In Hungary, Victor Orban’s government, like many states in this country, has imposed multiple hurdles between the person seeking an abortion and the actual procedure. They know that with abortion, time is of the essence.

The United States is now beholden to a vehemently anti-democratic Supreme Court. This is not new. For much of its history, the court has been a body that narrowly defined the Constitution’s “we the people” to mean “white men who own property.” That was the original assumption of the framers, after all. Their “we” did not include women, Indigenous peoples, Blacks, Asians, Catholics, or Jews. Arguably, the United States did not begin to resemble a democracy until the enfranchisement of Black people by the Voting Rights Act in 1965. When the Court gutted that same law in 2013, it reversed the steady expansion of our “we.”

Originalism, the perverse legal theory that came into prominence in the 1970s and now dominates the Court is reactionary at its core. It asserts that the law must be interpreted according to its “objective” public meaning at the time it was written, 1787. Originalism is a legal philosophy of stasis, which reifies a historical moment or moments. Although it must also consider the Constitution’s amendments at the time they were written, and it supposedly acknowledges legal precedent as well, it largely denies the dynamic course of history and change.

Static categories and strict borders are the bread and butter of the far right. In the leaked draft opinion and in the final version, Justice Samuel Alito repeatedly refers to the “unborn” as a single category, which subsumes every stage of gestation from the zygote (the fertilized diploid cell) to embryo to the human fetus only minutes before birth. Like originalism that seeks to freeze legal meaning in a historical moment, the reduction of a dynamic, metamorphosing conceptus to a single abstract entity—“the unborn”—denies both time and change.

The United States is now beholden to a vehemently anti-democratic Supreme Court.Pregnancy is indifferent to gender. Trans men can and do give birth, and this truth has meant the word “woman” is now often dropped from progressive discussions about pregnancy. However, an intact female reproductive system is necessary to become pregnant, and the years of a person’s fertility are limited. Biology matters.

As a teenager, I, not my boyfriend, was the one mortified by the prospect of a growing pregnancy. My daughter, not her boyfriend, faced the threat of a biological process she did not want to take over her body. A pregnant person is not a passive container for the “unborn.” Their feelings of alarm, unhappiness, ease, and joy are not separable from pregnancy. The very idea of erecting a clean border between pregnant person and fetus is absurd.

The big lie of the anti-abortion cause is that from conception onward, an “unborn person” exists, a homunculus just biding his time inside a motionless mommy container until he can push his way out. The fantasy is ancient and so powerful it can lead to the denial of well known biological facts. In 1857, the American physician Jesse Boring articulated what has mostly remained underground: “The fecundated ovum is not only embryonic man, already vital, but in an important sense, an independent self-existent being, that is having in itself the materials for development, being actually separated from the mother as from the father… there is… really no actual attachment of the placenta to the uterus.” The literal physiological attachment of fetus to placenta and the placenta’s attachment to the uterus, from which it is torn only at birth, is wished away.

Progressives may be careful to include trans men in their descriptions of pregnancy, but right-wing authoritarians don’t give a damn about making that distinction. There are only two sexes by their definition, and they are acutely aware that the fetus inside a woman could be male, an embryonic man, a precious commodity that must be protected at all costs. If by some magic, all fetuses suddenly became female, I strongly suspect the right-wing horror of abortion would dissipate.

A belligerent, theatrical masculinity accompanies all far right movements, not just in the United States, but in many places around the world. The fantasy of the unborn person serves to disguise the radical dependency of the fetus on the body of another person, a person the authoritarian right perceives through its rigid gender categories as a woman. To allow her to decide the fate of the growing cells inside her is to admit that she, and she alone, is the one who controls the future of those cells, which her body is nurturing, and the decision to nurture or not nurture them belongs to her.

It is important to acknowledge that misogyny drives anti-abortion thought and that this hatred turns on denial: I was never inside, connected to, and fed by a woman’s body. I was never a fetus and then a helpless newborn who relies on her or others like her, to survive. Dependence does not end with birth. Human beings are particularly vulnerable mammals who die without many years of care.

Over 90 percent of all abortions that have been performed in the United States have occurred in the first trimester of pregnancy. If the zygote, which becomes a multiplying ball of cells, is implanted in the uterine lining—a still poorly understood phenomenon in embryology—it may develop into an embryo and a placenta. Although the placenta, which is made from both maternal and fetal tissues, grows during the first trimester, maternal blood flow is not connected to fetal circulation until the second trimester. The tiny embryo is fed directly by secretions from the uterine lining, sometimes called “uterine milk.”

The very idea of erecting a clean border between pregnant person and fetus is absurd.When the embryo survives the first trimester—there are many natural miscarriages—the placenta begins its functioning as the mediator of pregnancy. It delivers hormones and nutrients to the fetus, allows for waste disposal, keeps the maternal and fetal blood systems separate, and orchestrates cellular exchange between mother and fetus, which creates microchimerism, the presence of fetal cells in the mother’s body long after pregnancy and the presence of maternal cells in her offspring.

There is no pregnancy and birth without a placenta, but its very existence as a between-organ must be suppressed in anti-abortion discourse because the complex placental-umbilical connection blurs the bodily borders the anti-abortion forces are desperate to maintain.

According to Planned Parenthood, girls under 15 are most likely to have second trimester abortions. Ignorance about pregnancy and fear of parents are the most likely causes of the delay. There are urgent medical reasons for later abortions as well—a dying fetus, a failing placenta, a fetus that cannot survive outside its mother. Now, in many places in our country, those decisions will not be made by the pregnant person and her obstetrician. The state will decide, and, because it will decide, there will be many more Agnieszka T’s.

In his majority opinion, the Catholic Justice Samuel Alito does not use the word “soul,” but the word and its religious meaning hover behind his references to the “unborn.” For millennia, the philosophical problem of fetal life has turned on the moral status of the conceptus. Does it have a soul? When does it get one? Is it a separate person or is it part of the pregnant woman? Or is it rather a potential person and must be valued for what it could become?

Aristotle did not believe human beings had a soul at conception. The embryo had a vegetative soul as a plant does, but the rational soul that belonged only to people came later. Male fetuses were ensouled at 40 days, females at 90 days. The inferiority of women was a given for the philosopher. Aristotle credited sperm with imparting the active, animate “form” or soul to the embryo. The female contributed just “matter”—inactive bodily stuff. Thomas Aquinas adopted the Aristotelian position: the soul was not present at conception. It arrived later in gestation. The Catholic Church dithered on the question for centuries until 1869, when Pope Pius IX proclaimed the fertilized egg “a soul.”

Both the Catholic Church and Protestant Evangelical anti-abortion advocates have adopted the biology of genetic determinism to argue for a soul at conception: a soul made of DNA. If genes are understood as the “blueprint” or “code of life,” the unchanging essence of a unique self, then the zygote, which has genetic material from both parents, can be viewed as a soul. In a Vatican publication, Enrico Berti returns to Aristotle to make exactly that argument: the sequence of DNA constitutes a “formula” or “form” for a human being. Berti advances genetic science as proof of ensoulment.

Although the sequence of our DNA does not change, genetic material is not an abstract blueprint or code for our traits. It is stuff inside every one of our cells and without the actions of the cell, that stuff is inert. Epigentic research has shown that many forms of stress affect gene expression. If a pregnant woman is oppressed by poverty and its constant worries, inhales toxins from polluted air, has a cruel partner who denigrates her, suffers the daily miseries of racism, sexism, or xenophobia, if she has fled her home country to take refuge elsewhere—all this may affect her gene expression and that of her fetus. The genome is not a soul fixed from conception onward. It is part of the dynamic unfolding of the biological processes that may transform two fused cells into a newborn.

The Supreme Court has returned us to the brutal era of womb legislation.The majority opinion overturning Roe and the 1992 subsequent decision which upheld it, Planned Parenthood of Eastern Pa. v. Casey, ignores the embodied realities of actual pregnancies. Alito asserts that there is no mention of abortion in the Constitution. There is no mention of much. Medical practices are not mentioned. Pregnancy is not mentioned, probably because no person who had been, was, or could become pregnant was considered to be among those described in the document’s grand opening flourish: “We the people.” Alito’s reading of constitutional rights is so narrow, his focus is trained on English common law precedents for the document written in 1787 and on the 14th amendment in 1869, which established citizenship for all native born people, that is, former slaves, and includes an equal protection clause that was used in Roe to argue for a right to privacy.

Alito claims “an unbroken tradition prohibiting abortion on pain of criminal punishment persisted from the earliest days of common law until 1973.” This distorts the history of abortion to a degree that is preposterous. As many have pointed out, when the constitution was written, abortion was widespread and legal until “quickening”—the time when a woman first feels fetal movement. When this happens is highly variable. Alito asserts that it is between the 16th and 18th week of pregnancy, but general estimates fall later, around the 20th week of pregnancy. He fails to recognize that the quickening judgement was made by the woman herself. No one else, after all, was in a position to know. Under common law, a woman needed her husband’s consent to do many things. Abortion was not one of them. The profound irony is that because most mid- and late-term abortions have been subject to legal restriction in the United States, Roe v. Wade essentially returned abortion rights to a common law standard.

From the 17th well into the 19th century, doctors, apothecaries, and healers of all sorts sold abortifacients “to restore the menses.” Indigenous women had long used herbs to induce abortions, and even slave women whose bodies were property and were often raped by their masters had formulas to rid themselves of unwanted pregnancies. Early abortion was big business, ubiquitous, and widely accepted. Alito spends considerable time on quickening, perversely citing cases of attacks on pregnant women as evidence of anti-abortion sentiment rather than what it was—an argument for making a violent crime even more heinous. Under common law a person had to be born to qualify as a homicide. But the justice then dismisses the quickening threshold because “the rule was abandoned in the 19th century.” In other words by 1869, the other date frozen in time by his originalism.

There is a broad scholarly consensus about why quickening lost its stature, a consensus Alito ignores. Abortion services were mostly run by people outside the medical profession, many of them women. Physicians began to organize to push out these “irregulars.” While earlier in the century, it was often poor, unmarried women who sought abortions, growing numbers of white, married, middle class, Anglo-Saxon women answered the ads placed in newspapers for a solution to their female problem.

Abortion became a Nativist issue as millions of immigrants—Irish, Italians, and Eastern European Jews—came to the United States. It is helpful to remember that many Anglo-Saxons regarded the newcomers as racially different. The Irish, for example, were inferior as “Celts.” “Scotch Irish” was a term adopted to identify Protestants. The idea of “whiteness” has always been present in the United States, but its definitions have changed over time.

By 1869, the Civil War was over. Black people were briefly enfranchised until Jim Crow took back their rights. White women pushed hard for suffrage and access to the professions, including medicine. They loudly asserted the right to “voluntary motherhood.” The doctors resisted. They lobbied legislatures to ban abortion as a dangerous procedure and a moral vice. Horatio Storer, head of Physicians Against Abortion repeatedly worried about changing demographics. What if Anglo-Saxons lost their political power? He wondered aloud whether the Western territories would “be filled with our own children or those of aliens.”

The music should sound familiar. “I want to thank you,” a Republican lawmaker, Mary E. Miller, said, addressing Donald Trump at a rally last Saturday, “for the historic victory for white life in the Supreme Court yesterday.”

By 1880, the physicians had won their crusade. Citing the many anti-abortion laws passed in the 19th century, Alito writes that there is evidence that “these laws were motivated by a sincere belief that abortion kills a human being.” And then, alluding to the history he obviously knows but wants to avoid, he asks, “Are we to believe that the hundreds of lawmakers whose votes were needed to enact these laws were motivated by hostility to Catholics and women?”

My answer is yes and by hostility to others as well. Misogyny, racism, antisemitism, and xenophobia mingle to make a poisonous stew. The Supreme Court has returned us to the brutal era of womb legislation, to the terrified 16-year-old in 1972, and to countless others like her whose reproductive bodies have become property of the state.