Questions and Crimes: Golan Haji on Art and Letters in the New Syria

Translated and Introduced by Fady Joudah

“But there is another situation in which imagination enjoys a similar preeminence, not as the only mental faculty which is alert but as the only one which is free; a situation in which other forces are certainly awake, but in chains; in which the real world in all its treasures and truths is no longer unknown to us, but locked away.”

–C.G. Joachmann

*

I had been thinking about the proliferating language around images lately, especially with regards to Gaza, and how this language almost always relies on European art, from the Renaissance to Surrealism, to meditate on the horror of the first live-streamed genocide—a nomenclature as affirmative echo of the problematic of antecedence in western culture, a creator of the genocide of Gaza.

Why don’t these gifted writers study the works of Palestinian artists that span decades to learn from Palestinians what they have been saying about cruelty and art? Not infrequently, the questions of the past that is never lost and is irreplaceable in western art arise like a fascism, or a subordination to what remains of its dialectic nature, that relies on myth to legitimate fascism’s inseparable relation to beauty. Another way of thinking about this is to think of censorship.

I was also thinking of Sliman Mansour’s art. And shared these thoughts with my friend Golan Haji, the Syrian Kurdish writer in Arabic who lives in France, and whose mother had recently died in Qamishli. He was unable to see her because the French government insists on arbitrary, absurdist violence against its immigrants.

In response, Golan Haji shared with me his essay, “Questions & Crimes,” which he had just published for the anniversary of the Syrian rebirth. Instantly I decided to translate it. But encountering the layers of censorship and self-censorship that impose themselves on an Arabic text in English astonished me yet again. The pull toward explanation, footnotes, forcing a journalistic clarity in a literary piece that engages the politics that frame it.

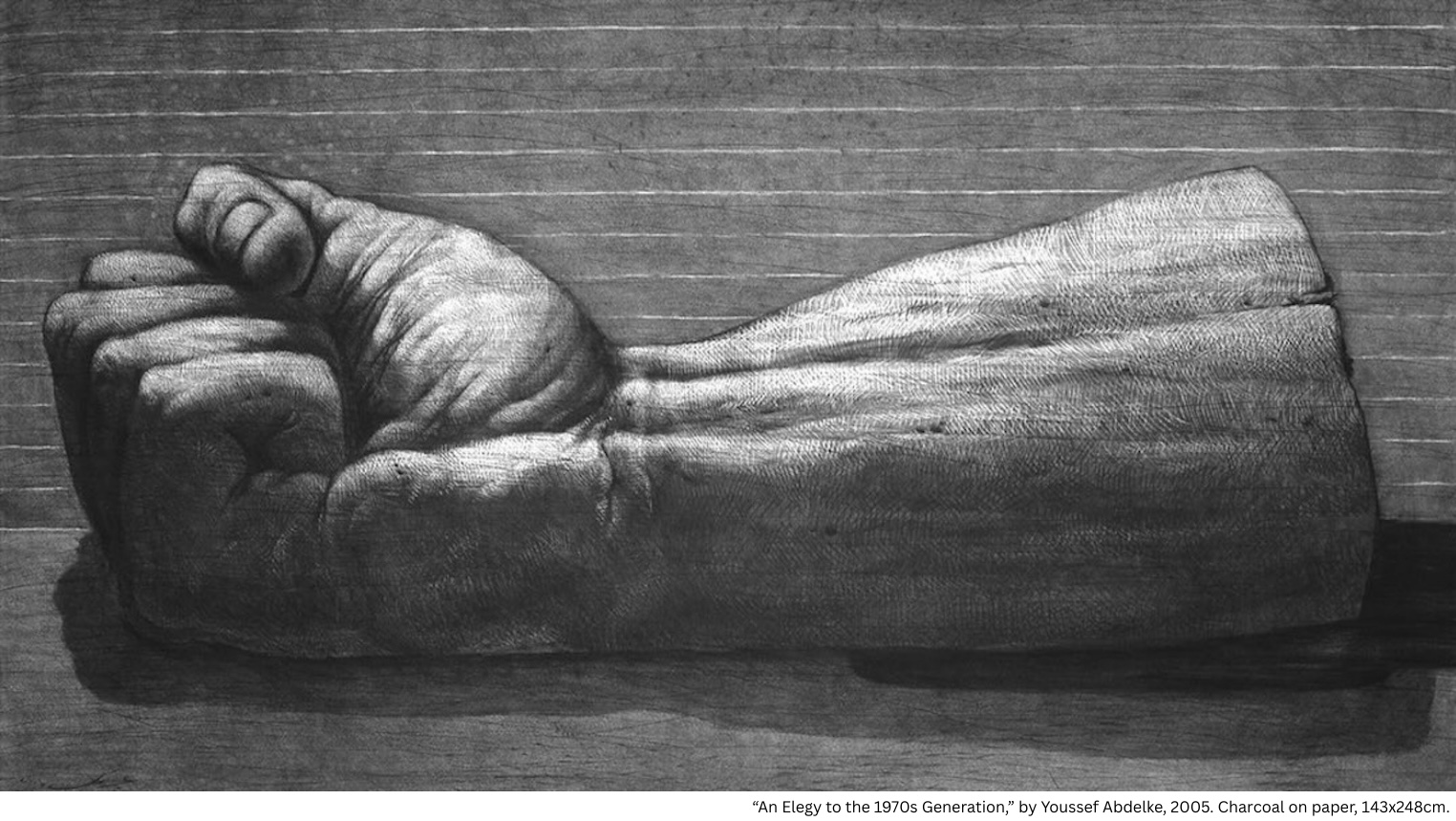

“Knife and Flowers,” 2018. Charcoal on paper, 104x104cm. (All images by Youssef Abdelke.)

“Knife and Flowers,” 2018. Charcoal on paper, 104x104cm. (All images by Youssef Abdelke.)

In reminding us that a triumphant Syrian history of overcoming censorship in Arabic exists, Golan Haji also leaves the obvious unsaid. Is there a literature in any alphabet that does not struggle against censorship in order to become worthy of being art? No is the answer that does not come with the disclaimer that not all censorships are created equal.

Perhaps another question is how English enacts its censorship modes on its literary practitioners. One mode is clear: by universalizing the insurmountable, limiting nature of censorship in other languages. Grievance (and the restitution it demands) replace the emancipatory imagination.

Gaza is progressively becoming a literary property of English. This, in no small part, is due to the genocide of Gaza itself being a property of English. And English (“Which English?” a favorite rhetorical move likes to interject itself here) loves ownership and the transformative process of what it owns as evidence of “evolutionary” progress.

–Fady Joudah

_____________________________________

Questions & Crimes

By Golan Haji

Aboard this train, an entire country. And newspaper presses, and cubicles for staff.

No matter where the passengers disperse, the train walls surround them. Mr. Q is one such passenger. A traveler who dislikes travel. His supervisor appears as a ticket conductor and reprimands him for doing nothing. Mr. Q. replies, “How can anyone work aboard a train moving like a lunatic?

The supervisor says, “You’ll get used to it,” and directs Mr. Q to his workstation on the third level of the train.

Unexpectedly the train cars agitate and the train screeches to a halt. Some passengers toss out a corpse before its stench becomes unbearable to others. The train resumes its journey. And Mr. Q is screaming: “But I don’t get it, I don’t understand.”

A passenger next to him hands him a cigarette to calm him down: “Screaming won’t help you. You will encounter so many incomprehensible things in the coming days.”

*

The above passages summarize events in George Salem’s 1965 story, “The Train.” I boarded it when the news reached me in 2025 of a new railway linking Syria to Hijaz.

Syrians have endured a lot during their first transitional year since the fall of Bashar Asad’s regime on December 8, 2024. The transition from Asad’s “Useful Syria” to Al-Sharaa’s “Pragmatic Syria.” The people disembarked the out-of-service Baathist train and are waiting for the trains the new rulers promised them. High-speed trains that will aid the bleeding country, carry it from the Umayyad age to the age of AI and back.

Those who liberated Damascus write the Syrian success story the way American success stories are written.

The overwhelming majority of Syrians remain trapped in the tunnel of need and fear. Whenever light flashes, they hesitate, recoil. The light at the end of the tunnel might be a new explosion in a church or in a bus parking lot. Or it might be one of those new bombs that “international peace” efforts drop now and again: on Raqqa, on Aleppo’s old city, or on the hills of Afrin. Syria lives on like a miracle despite repeated bullets to the head that are more fatal to dislodge than to leave in place.

*

Loaded with questions and crimes, the Syrian train transports its people to the present. They have enough past to feel proud or disgusted. They know how previous calamities taught some of their victims the wrong lessons in forgiveness and forgetting and turned them into butchers. In this present, it’s possible that most passengers didn’t notice the abducted women from Druze and Alawite mountains. Nor did their eyes shed tears over the burning library that raiders furnished with the ashes of seven thousand books, which the novelist Mamdouh Azzam had collected over fifty years inside his house in Suwayda.

Censorship is a primary muse for creativity. Through extortion and threat, political and moral policing continue to impose their will.

Coeval is the liberation of Damascus and the annihilation of Gaza in the age of civilizational genocide of “human animals.” Attention please, in these times of incremental costs of living, we would like to entice the arrival of investors with irresistible opportunities in the land of the wretched. Workers will be able to relocate from the burning universe of bribes to the fiery one of taxes.

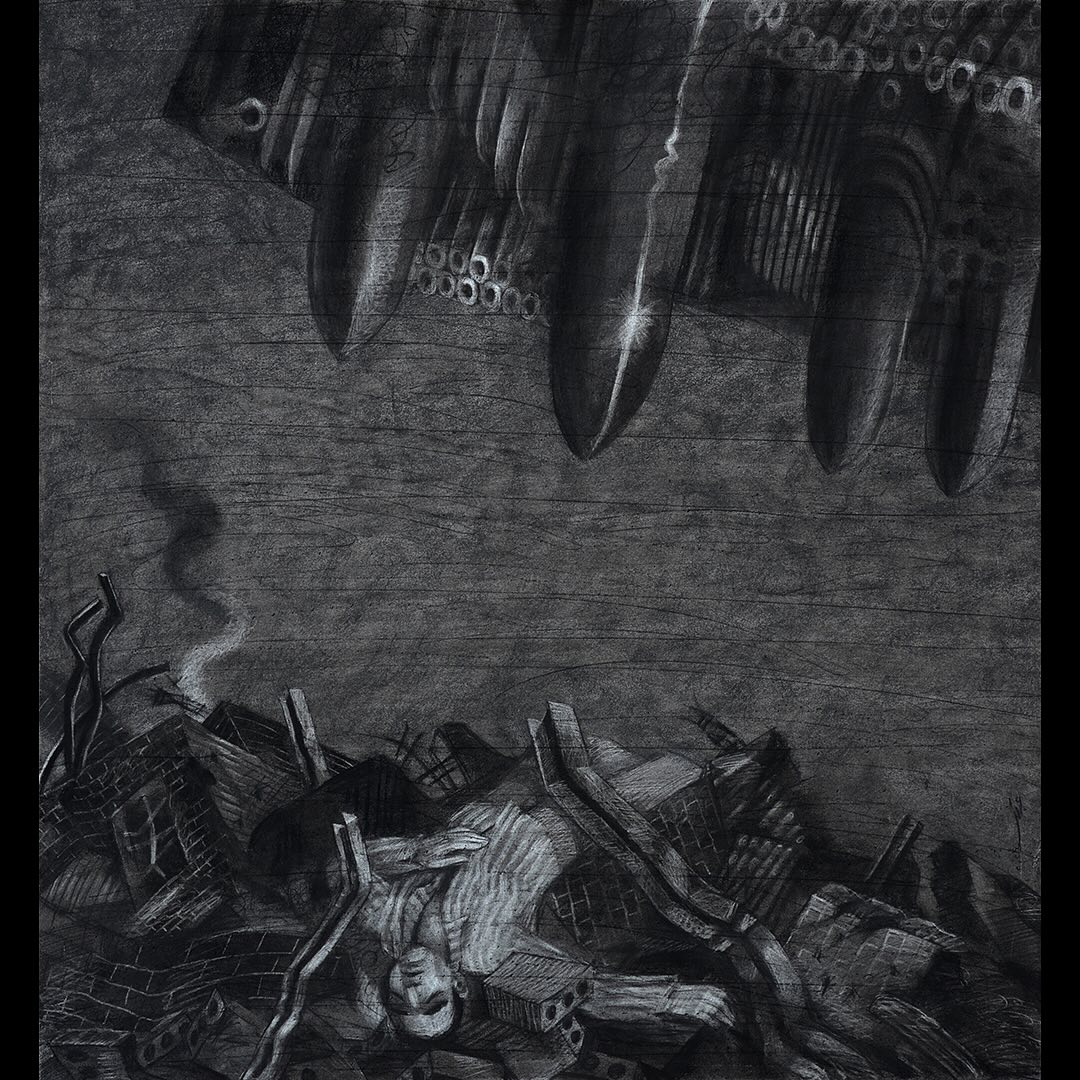

“Diaries of Gaza,” 2024. Charcoal on paper, 105x96cm.

“Diaries of Gaza,” 2024. Charcoal on paper, 105x96cm.

Those who liberated Damascus write the Syrian success story the way American success stories are written. The liberators ascribe to their future the paradigms of luminous affluence in Gulf states: malls, towers, hotels through which life’s catastrophes are transformed into exhibits one might encounter in galas for grand prizes. And what will the children do? The orphaned children of war will recite the songs of commercials instead of national anthems.

Syria’s transitional president has succeeded in lifting the siege. He also visited the White House of the grand imperial accomplishment. How scandalous the attainment. That the one who removes you from the international feast is the one who generously reserves your seat at the table. The one who hunted and punished you now celebrates your courage. He killed you, and you survived. Your historical victory is your reward for your historical abasement.

As the classicist poet Badawi Al-Jabal (1903-1981) wrote decades ago, “Suave humiliation become redemption.” But today’s traditionalist poets, who accompanied the liberation parade from Idlib to the Umayyad capital, get off on the cognates of salvage and salvation and on the prefixes of survival and revival.

*

Syrians are no longer numbers on the foreheads of the murdered in Sidnaya prison. They are now numbers in stock markets, exchanging the secrets of repentant militias and mujahadin for the secrets of big corporations that surveil the world, veiling what they like and crushing what they don’t. While Syria is maintained as a coin whose two faces are Asad and Al-Sharaa.

William James, the godfather of pragmatism, linked the value of faith to currency, spiritual virtue to utility. He advised authors to extract from each word its exchange amount. Marginalized and unknown artists and writers have become a standard of failure. A bitter truth. Most of them are unemployed and produce nothing but illusions. Killers, however, are practical and can’t stand losers. Art and literary projects become like residue that sticks to more useful and prioritized societal missions. Publishing a book in the literature of survival doesn’t cost as much as a barrel bomb the Asad regime’s helicopters dropped over Darayya. The budget of a movie about the White Helmets is less than the price of a missile that destroyed a bridge in Deir Ez-Zour.

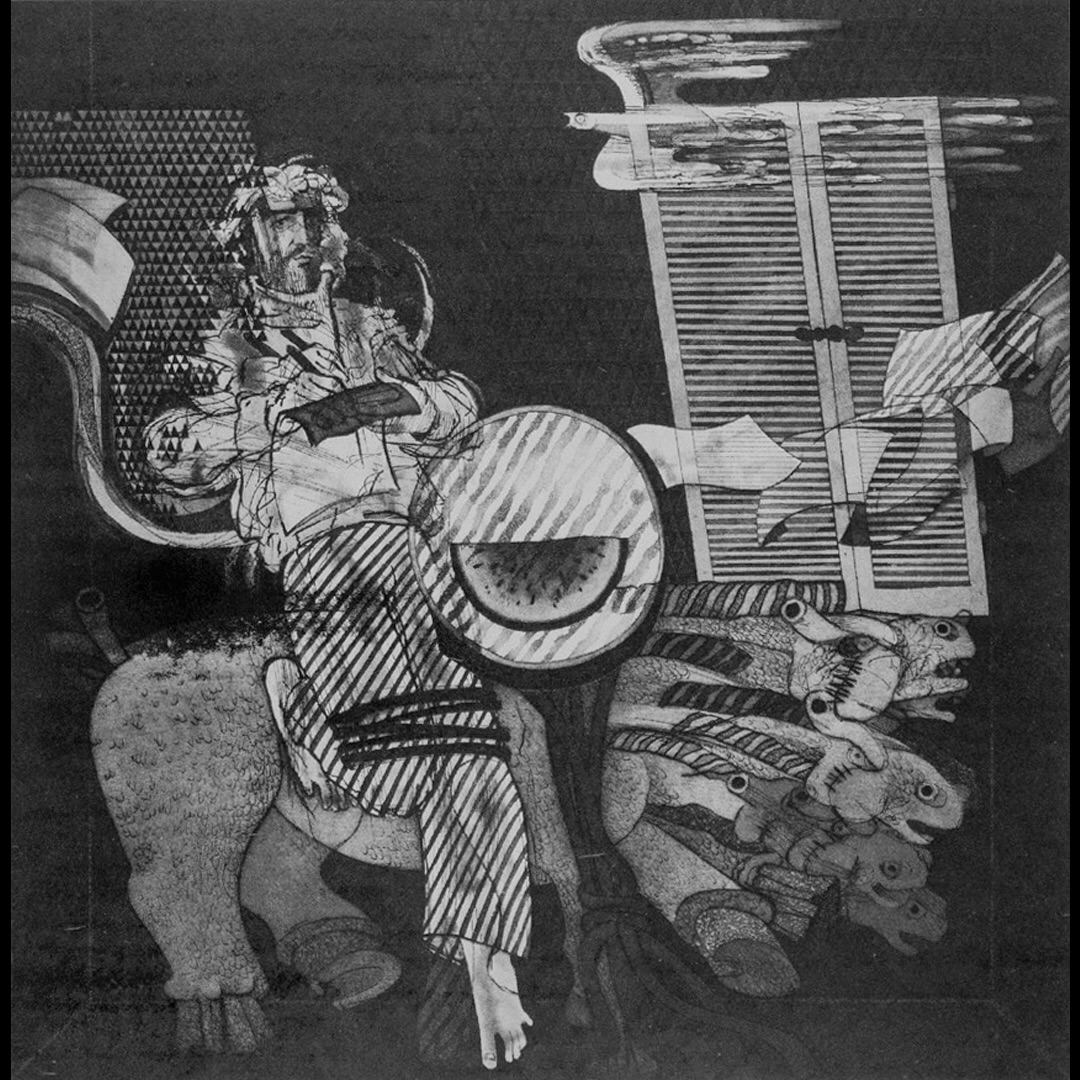

“Evening Place,” 1986. Engraving on copper, 49.4x49cm.

“Evening Place,” 1986. Engraving on copper, 49.4x49cm.

If you happen to be a productive writer or artist, you might, with luck or by the grace of God, receive good suggestions from virtuous gatekeepers to help you sidestep certain pitfalls and ensure greater safety for your aesthetic project and your general wellbeing. This is conditional freedom. And if experience taught you anything, it’s how rapidly the watchful eye stings and recoils when it disapproves of where you stand. Remember what Badawi Al-Jabal wrote: “Surrounding me are two satirists, eternity and the unknown.” So feel free to exchange God for Holy, Arabness for Islam, sect and ethnicity for nation and state, or Palestine’s flag for a watermelon.

What has censorship outside Syria, outside Arabic, imposed on Syrian writers, I wonder?

Censorship is a primary muse for creativity. Through extortion and threat, political and moral policing continue to impose their will. They might benefit your name in the cultural market if your book is banned in Kuwait, let’s say. Or if a you’re awarded a German prize that is swiftly withdrawn. Or if you took off your clothes and stood naked in a public square to demonstrate against the war. But if you go back in time a little, to the political theatre of Mohammad Al-Maghout, you’d probably see how Syrian culture succeeded in overcoming censorship and its checkpoints.

Still, self-censorship is the most devious concocter of self-deceit. Like a vulgar cowardly high priest who knows too well the maze of the permissible and the forbidden, he speaks to you inside your head, guts, and nightmares, waging a civil war between you and your shadow. What will you, free-willed writer, compromise on? What will your triumph look like if you fight against yourself and you are the winner and the loser?

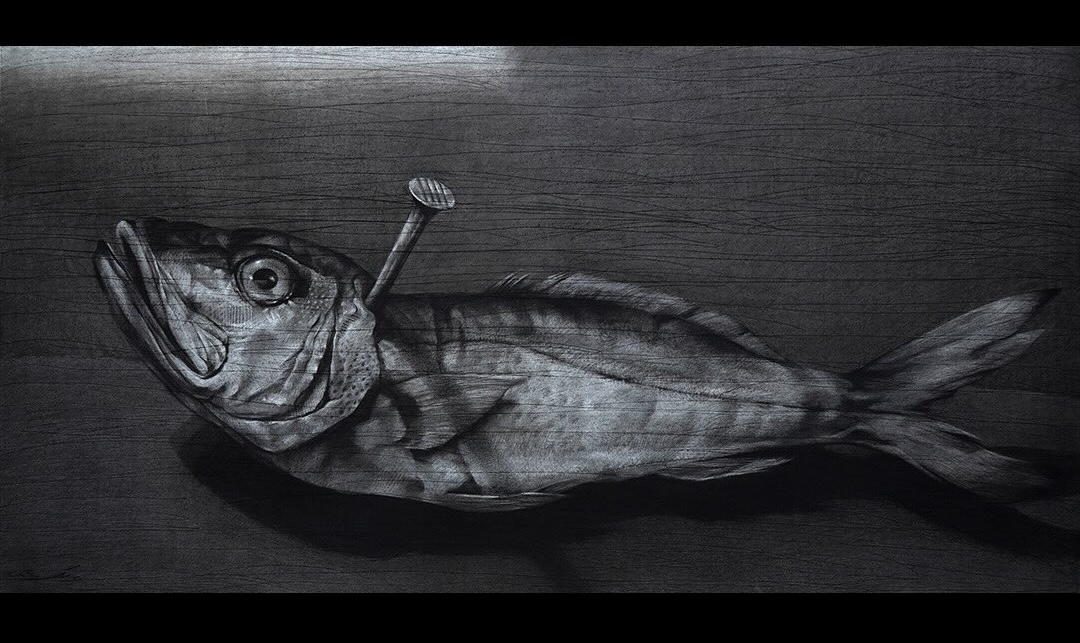

“Fish and Nail” 2024. Charcoal on paper, 99x194cm.

“Fish and Nail” 2024. Charcoal on paper, 99x194cm.

What has censorship outside Syria, outside Arabic, imposed on Syrian writers, I wonder? And how has that censorship, primarily in European languages, influenced self-censorship within the Syrian writing in Arabic or otherwise?

The marks of this secret war is as evident in Syrian writing today as are the scars on tortured bodies and ruined cities. Symbols and metaphors are the most astonishing of these scars. Censorship played the role of the reverent teacher who developed these skills in Syrian authors who said one thing and meant another.

In the summer of 2025, I spent some time with new Syrian writing. Yeser Berro gave me pause in his recent novel, “The Song of Cruel Spring”:

He saw himself sitting with his parents behind a window in their old house. His mother and father were in an embrace, unaware of his presence, as if he were a time. Through the window, they saw an army of mounted purebred Arabian horses. The entire Syrian people galloping toward some destination. An overwhelming scene. Terrifying. Mesmerizing. The ground shaking under millions of hooves. But that was the only sound. No human conversation, no shouting. The people in full silence. It was a new kind of silence he had not experienced. A silence that rides a horse and heads towards what exactly? His memories of his parents kept interrupting his imagination. Their visits to the beach. A new year party. While the horses were flicking sand like fireworks.

The violence of experience can liberate the imagination and diction of young writers. Now and again, imagination needs a liberation that seizes no reality and guards against the open-ended vengeance a wretched present pursues against a wretched past. Dreamers will be free of “leadership charisma,” the scarecrows of clan heads, and the sham auras of those who peddle in religion.

Our reality is a stranger to hope. The arts are a subdued call to a confrontation, a quarrel that contemplates cruelty, not optimism. In the carnival of winners, art and literature do not forget those who failed: those who fought hard to save their own lives only to become witnesses to the summary of their lost lives.

_____________________________________

Fady Joudah’s most recent poetry collection […] was a finalist for the National Book Award and winner of the Lenore Marshal poetry prize.

Golan Haji

Golan Haji is a Syrian-Kurdish poet, essayist and translator with a postgraduate degree in pathology. He lives in Saint Denis, France. He has published five books of poems in Arabic: He Called Out Within The Darknesses (2004), Someone Sees You as a Monster (2008), Autumn Here is Magical and Vast (2013), Scale of Injury (2016), The Word Rejected (2023). His translations include (among others) books by Robert Louis Stevenson and Alberto Manguel. He also published Until The War (2016), a book of prose based on interviews with Syrian women.