Questioning the Borders of Nonfiction to Tell the Story of an Exceptional Life

Levi Vonk on All God's Dangers and the Power of Collaborative Oral History

In 2014, book critic Dwight Garner published a lament in the New York Times for a seemingly forgotten literary masterpiece, the oral history All God’s Dangers. Published in 1974 by then-Harvard doctoral candidate Theodore Rosengarten, the autobiography was narrated by Nate Shaw, an illiterate “black tenant farmer from east-central Alabama.” It was a collaboration as inventive as it was radical.

At the time, oral history was still largely confined to academia in the US, and its aim was frequently not to capture a singularly gripping drama so much as to provide a socio-linguistic “snapshot” of a place or people. But Rosengarten and Shaw changed all that.

All God’s Dangers is a wild and sprawling odyssey in which a “black Homer” recounts his adventures in a manifestly transcendent Southern argot. It promptly won the 1975 National Book Award in general nonfiction, beating out All the President’s Men and Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. But, Garner bemoaned, while those books had rightfully left their mark on the literary landscape, All God’s Dangers had, inexplicably, “all but fallen off the map.”

Except, it hadn’t been completely forgotten. I was reading it at that very moment, in fact, probably for the third or fourth time, in what had become something of a ritual for me. I’d met Ted—I call him Ted—at the College of Charleston in South Carolina, where I attended as undergrad. I was never officially his student; another professor suggested I email Dr. Rosengarten for advice on an essay I was writing on migrant farmworkers, and without hesitation Ted invited me to discuss the draft at his home over dinner.

I hailed from a small town in rural Georgia, and he was the first writer I’d ever met. It wasn’t until I was alone in his study—Ted was busy prepping pork chops in the kitchen—that I thought to Google him and nearly had a heart attack after seeing he and Shaw had won a National Book Award. I was not a particularly gifted pupil—“What’s with all this bullshit fancy language,” Ted remarked later while striking out an entire page of my draft, “just say what you mean in your own voice”—but I had an intense desire to learn, and Ted was generous or crazy enough to indulge it.

All God’s Dangers naturally became my bible, an urtext of oral history that revolved around the sanctity of the spoken word, especially the words of those who could not read or write themselves. To me it was not so much a forgotten book as a sacred one, not a lost text but the kind kept locked away in an arc of some covenant, to be presided over by an enigmatic literary clergy to whom I hoped to one day belong.

After graduating—and inspired by Ted—I decided to become an anthropologist, to listen to the stories of people who I might otherwise never encounter. I left to conduct fieldwork in Mexico, my rationale being in part that the majority of Alabama’s farms today are no longer worked by black tenant farmers but by Mexican and Central American immigrants.

And so, armed with my dogeared copy of All God’s Dangers, I headed further south than the South, maybe vaguely hoping that I might encounter another Nate Shaw, someone who would bless me with language the same way Ted had been blessed.

He found me on a migrant caravan. His name was Axel Kirschner, and he said he’d just been deported from New York, the place he’d lived nearly all his life. When he spoke, his arms flailed wildly around his head, as if he was flinging the words out of his body.

In contrast to Shaw’s elegant diction—which is like a storm gathering on the horizon, a slow-building momentum that rolls with quiet intent until it bowls you over—Axel’s voice was a succession of mercurial lightning bolts that set whatever was within striking distance aflame. I’d never met anyone like him, but I knew immediately that he was the kind of person I needed to listen to, and to listen to carefully. That listening eventually revealed a secret: Axel was a hacker. And through his hacks, he ended up revealing a ring of massive corruption that led to some of the most hallowed halls in all of Mexico.

All God’s Dangers naturally became my bible, an urtext of oral history that revolved around the sanctity of the spoken word, especially the words of those who could not read or write themselves.

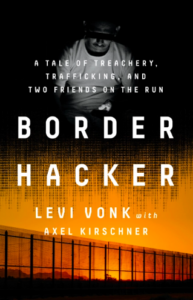

I fervently began documenting Axel’s journey—past human traffickers, crooked priests, and anti-government guerillas—as well as our unlikely friendship along the way. Now, almost exactly seven years to the day that we met, we’re publishing a book together, Border Hacker. A keen reader will spot the influence of All God’s Dangers throughout.

In a way, though, Border Hacker’s biggest homage to All God’s Dangers lies not in its similarities, but in its differences. In order to tell Axel’s exceptional story, I felt as if I needed to question the borders around what had been declared acceptable within the craft of nonfiction, and to push it into new territory, just as Ted and Shaw had done a generation before with oral history. What Shaw definitively proved was that even illiterate narrators can be prodigious literary minds. Someone who has really lived a story is sometimes also the best person to really tell it.

That’s why I’m so inspired by All God’s Dangers. Ted could have recounted Shaw’s story from his own perspective, quoting him where appropriate, but he didn’t. Instead, he listened. And, yes, Ted is still “there” in the book—he is in the editing, the innumerable hours of transcribing and arranging and returning to Shaw for more—but on the page he’s nowhere to be found. Having the political vision and discipline to do that is a gift.

However, I must admit, the things I love most about the book—Ted’s conscious absence, his willingness and wisdom to step back—are also what nagged me at times as his would-be apprentice. While reading All God’s Dangers as a college student, I desperately wanted to know what Ted felt as he sat on Shaw’s porch in the sweltering Alabama night recording interviews on finicky magnetic tape.

I yearned for his inner monologue—not to replace Shaw but to be in conversation with him, to learn how Ted was changed by the things he heard Shaw tell him, just as I was changed when I read them. The Ted I knew was an older, incredibly accomplished professor, and I saw him in some sense as a literary father. But, as with all fathers, I wanted to know who he was before I met him, and why a young Jewish man—who was also not exactly safe in that part of Alabama either—would choose to risk something of himself for a greater cause. Did he, like me, have doubts?

One might muse, for instance, that All God’s Dangers was not so passively forgotten, as Garner lamented, as actively repressed. One of the book’s pivotal moments is when Shaw—a member of the communist Alabama Sharecroppers Union—unflinchingly shoots at white police officers fraudulently confiscating a neighbor’s livestock, an action that most of America—in 1974 as in 2022—was certainly not interested in enshrining in cultural memory.

As I traveled alongside Axel, I was afraid that America wasn’t ready for our story either. Today’s immigration policies are not only similar to the segregationist ones Shaw battled in Alabama but actively inspired by them. These laws have stripped Axel of a country and put his life in peril. In order fight back, he (and I with him) has done things in the name of survival—like Shaw—which are not legal, even if they are just. We have run from border patrol agents and flouted immigration checkpoints.

At one point, Axel was kidnapped by a man with powerful connections to the Mexican state and forced to hack other prominent government officials on his behalf. With nowhere else to turn—it wasn’t like we could call the police—I said to hell with professional boundaries and busted Axel out myself. Because of these dangers, Axel must hide who he is in order to survive.

Crossing those kinds of personal borders forced us to also reconsider how to tell our story on the page. I returned to All God’s Dangers for inspiration. Just like Shaw, I knew that Axel’s persona was too vivid, and his language too lyrical, to be wasted on me simply quoting him. Our greatest strength, Axel and I decided, was in the dialogue between us, both of our voices speaking back and forth to each other about the great violence that Axel is forced to navigate. Instead of one first-person narrator, we required two, which, as far as we know, is something of a novelty within mainstream nonfiction.

This gives Axel space to speak for himself and tell his story on his own terms, even when he contradicts or criticizes my account of events. It is by no means a perfect solution to his predicament—Axel is still undocumented, and I am still the one writing this essay—but it is our humble attempt to do something different within the genre.

In the years since Garner’s article, All God’s Dangers has shot back up the best-seller list, and new translations are forthcoming in Mandarin and Dutch. Maybe younger generations are rediscovering a secret truth in the oral history that first dared to do more than its predecessors—that only by breaking with the forms of your fathers can you honor what they themselves strived toward most fervently.

__________________________________

Border Hacker by Levi Vonk with Axel Kirschner is available now via Bold Type Books.

Levi Vonk

Levi Vonk is an author, anthropologist, and the Guerrant Professor of Global Health Equity at the University of Virginia. His first book, Border Hacker, was a national finalist for the 2023 Chautauqua Prize and the 2023 Juan E. Méndez Book Award at Duke University. He grew up in rural Georgia.