Queer Correspondence: On the Radical Potential of Epistolary Poetry

Madeleine Cravens Considers the Poems That Explore the Spaces Between Public and Private

In the beginning of Swann’s Way, Proust’s narrator recalls an evening of childhood anxiety, sequestered in his bedroom as his parents host a dinner party downstairs. Overcome with loneliness, the boy writes a letter to his mother. Proust describes the immense relief of this act: as soon as the letter is created, the boy feels connected to his addressee, believing that between them, “the barriers were down… an exquisite thread joined us.”

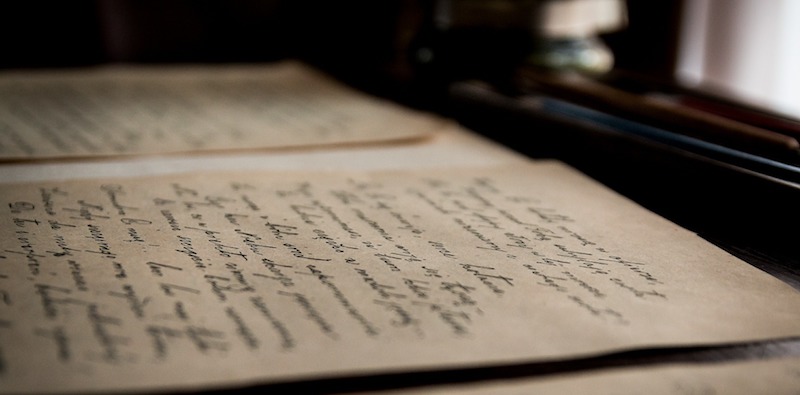

We never get to read the letter itself. Sometimes I wonder if this is what separates poetry from fiction. If most poems—or just maybe the poems I love best—are letters made public. Exquisite threads, our brief and urgent utterances to each other.

When I was twenty-four, I met an older poet I’ll call K. At the time, I wrote poems in the early morning, before my office job. I never intended for anyone specific to read them. One night in January, I went alone to a reading in the East Village. I noticed K across the room because she seemed annoyed and was wearing a pink coat. I didn’t know any poets. I had no idea who K was.

After the reading, we both stood on Second Avenue, waiting for the light to change. It was raining; neither of us had an umbrella. We looked at each other. “Hi,” she said, saying her name, extending her hand toward me. I followed her to a nearby bar.

There is, I think, an inherent human impulse to direct one’s inner monologue to a “you.” This inclination is by no means exclusive to poets: it is why people pray, debate, text, and go to therapy. But I am struck, over and over, by the ease with which poems offer a container for correspondence. How effortlessly they become epistolary.

That January, the January of 2020, K and I became instantly, terrifyingly close. In the first week of our friendship, we walked for hours. We talked about our families, other cities we had lived in, people we loved. Whenever we left each other, there were hundreds of things I still wanted to say. I stopped being able to sleep. I spoke to her in my head.

T.S. Eliot, in a 1954 essay entitled “The Three Voices of Poetry,” wrote that “a good love poem, though it may be addressed to one person, is always meant to be overheard.”

The epistolary form shares this paradox. Letter poems convey a sense of private communication between two parties, but are ultimately intended to be read by an audience. They bring our individual intimacies into the public realm.

For this reason, I’ve become particularly interested in epistolary poems by queer writers, and in the radical potential this kind of work holds.

More simply: that January, I began to write, constantly, almost compulsively, to K.

In her essay “Intimacy, Epistolarity, and Queer Mourning in the Work of James Schuyler’s Poetry,” Siobhan Phillips uses Schuyler’s work to outline the central characteristics of epistolary poetry, or rather, what exactly distinguishes letter poems from other poems that engage a “you.” These factors include a specificity of address, an acknowledgement of the poem’s materiality as an object, and an “ineradicable distance” between the speaker and the addressee.

The “you” of the letter poem is never universal. It is vivid, particular, and far-off. It follows that the epistolary poem itself has an urgent function: it must bridge a gap.

As Schuyler wrote in his 1972 poem “Letter to a Friend,”

A trove of glass

within a

cabinet

near my

knees

I wish I were on

my knees

embracing

yours.

Schuyler goes on to fill the poem with intimate recollections of his “you:” his suits, his behaviors, certain things he said. Ultimately, Phillips argues that Schuyler’s epistolary poems, at once highly familiar and intended to be read by many, were indicative of a fluid mode of sociality that transcended mid-twentieth century binary conceptions of public and private life.

Here, Phillips draws on the work of Lauren Berlant, who, in their 1998 essay “Sex in Public,” written with Michael Warner, famously argued that such a divide—between a sequestered, intimate “personal life” and a forward-facing, non-sexual external life—was a key feature of hegemonic heterosexuality.

For queer writers, for queer people in general, privacy is complicated. We want to be alone, but we want to be alone at our own choosing. We do not want our intimacies to be relegated to the world of the unseen.

The more epistolary poems by queer writers I seek out, the more networks of correspondence I find. Elizabeth Bishop, notoriously private about her homosexuality, wrote several letter poems to women in her life. In her 1954 poem “Letter to N.Y.,” dedicated to Louise Crane, Bishop begins,

In your next letter I wish you’d say

where you are going and what you are doing;

how are the plays, and after the plays

what other pleasures you’re pursuing;

Like Schuyler’s letter poems, like Proust’s boy in his bedroom, Bishop writes from a place of distance. The poem becomes a vessel for connection. In her 1955 poem, “Invitation to Marianne Moore,” Bishop enacts a similar gesture, asking Moore to cross the Brooklyn Bridge for a visit. In uncharacteristically casual language, Bishop describes a day she and Moore could spend together: “we can sit down and weep; we can go shopping.”

Bishop’s epistolary work draws on concrete physical locations in New York: bridges, theaters, cabs, the harbor. But the abundance of public life in her letter poems to other women is made complicated by the existence of the work itself. Why were these letters written? Why did Crane and Moore need to be convinced to inhabit the world alongside Bishop in the first place?

Perhaps counterintuitively, queer epistolary poetry has opened my eyes to forms of intimate relationality outside the dyad form of the long-term couple. June Jordan wrote many epistolary poems throughout her career, to various friends and lovers, though an abundance are dedicated to a specific woman named Haruko. After Jordan’s death in 2002, Marilyn Hacker wrote “Elegy for a Soldier,” a poem addressed to Jordan that also functions as an homage to Jordan’s work and life.

Hacker begins the elegy by speaking to Jordan directly, placing Jordan in a scene of queer eroticism, making her vividly alive again. Hacker writes,

The city where I knew you was swift.

A lover cabbed to Brooklyn

(broke, but so what) after the night shift

in a Second Avenue

diner. The lover was a Quaker,

a poet, an anti-war

activist. Was blonde, was twenty-four.

Here, Hacker is external to the romantic love plot, but she occupies an arguably equally or more important role: that of a witness, a record-keeper. Like the poems of Schuyler and Bishop, Hacker’s writing for Jordan originates from a place of separation. Jordan is no longer alive. Still, the poem, which is filled with moments of true intimate recollection—Hacker pictures Jordan standing “alone in a tall bay window of a Brooklyn brownstone”—places the two poets in correspondence, and brings queer friendship into the foreground, destabilizing the idea that tenderness ought to be relegated to one’s sex life.

The epistolary poems that excite me most are rarely letters from one living monogamous partner to another. I am interested in the poems that capture the speech of longing, and in the poems that attempt to make public illegible, incongruous connections.

In “Sex in Public,” Berlant and Warner write, “Nonstandard intimacies would seem less criminal and less fleeting if, as used to be the case, normal intimacies included everything from consorts to courtiers, friends, amours, associates, and co-conspirators.”

From the beginning, my dynamic with K fell outside the realm of the standard. Our friendship confused many people, who wanted to know if were sleeping together, if we were in love, if she was my mentor—who wanted to know what the parameters of our relationship were.

For queer writers, for queer people in general, privacy is complicated. We want to be alone, but we want to be alone at our own choosing.Recently, I sat down across the table from her in the same red booth of the bar we first spoke in, where we hid from the rain. I no longer live in New York, though I had come home to visit. We ordered coffee. I had become confused about what exactly constituted an epistolary poem. I wanted to write this essay. I was having a hard time with it.

I asked K about “Half Light” by Frank Bidart, a poem she had showed me early on in our friendship. In the poem, Bidart’s speaker imagines a conversation with a man who he furtively loved, a man named Jim, who has since passed away. Bidart writes,

When I tell you all those years we were

undergraduates I was madly in love with you

you say you

knew. I say I knew you

knew. You say

There was no place in nature we could meet.

I didn’t know if this poem was a letter. Or just a regular poem that that employed direct address to a distant subject. K thought for a while.

“It is,” she said. “I think it has to do with impossibility.”

I remembered, then, the first months of knowing her. I remembered the first poem I wrote that felt indicative of my actual speaking voice, rather than a fragmented interpretation of it. I remembered, also, that I had written the poem out of mild anger.

We had been sitting on the floor of her apartment, eating a Peruvian chicken dish she had made. “You know,” K said to me, putting her fork down. “I don’t even know that much about you.”

At the time, I resented her acknowledgement of the newness of our friendship, though now, of course, I see how true it was. We were strangers. I took the subway home to Brooklyn. When I couldn’t fall asleep, I opened my email. “K,” I wrote, but not K, I wrote her real name, her nickname. I wanted to write something that would make her know me, that would tell her about my life. It became a poem, which I called an “An Explanation.”

The poem doesn’t call itself a letter. It doesn’t address a specific second person—I deleted that part. But at its heart, I feel it is epistolary, because it was written with the intent of being in dialogue.

Since then, there have been other people I have written to. K writes to me, and also to others. We exist within a field of correspondences. I think, sometimes, of an often-repeated fact, that stanza comes from the Italian word for room. A cliché, probably. But when contemplating public and private life, queer identity, and our exchanges of letters, it is perhaps helpful think of the poem as a space we build. We can decide who looks in. Some readers may be able to understand the arrangement of the furniture, to hear legible language. Some might be met with opacity. One person might understand everything.

I want to make a poem. I want to make a room where we can meet. I sit down and close my eyes. I picture your face, your hands, your jewelry. When I begin to write, I speak to you directly. I create the thread between us, knowing I can be seen, allowing myself to be overheard.