Bedtime Stories From Toni Morrison: Priscilla Gilman on Her Singular Literary Upbringing

The Author of The Critic's Daughter in Conversation with Lauren LeBlanc

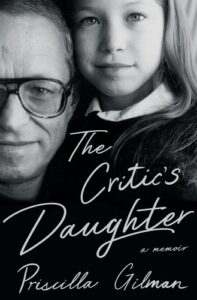

Family memoirs are never about one thing. There’s always a compelling domestic story; in her new memoir, The Critic’s Daughter, Priscilla Gilman tells a fascinating story about her dynamic parents and the literary world that they inhabited. But good memoirs always involve a secondary subplot (or several) that undergirds the memoir’s dramatic arc—otherwise, what you’re reading is personal background that could be whispered at a dinner party. One need only to look at Gilman’s title to grasp that her book is also a story about criticism.

While The Critic’s Daughter concerns itself with her parents’ marriage and its aftermath, it’s very much a book about the way one develops and nurtures a fascination with the arts through enthusiasm, criticism, and commerce. The elder daughter of the legendary literary agent Lynn Nesbit and the late theater critic and professor at Yale Drama School Richard Gilman, Priscilla herself is a critic as well as a teacher, writer, and advocate.

Coming of age in the 1970s and 80s, Gilman witnessed the collaborative but often combative dynamic wrought by the tension between her two brilliant, loving parents and the way they engaged with art. Gilman’s book explores the various ways that people can chart a life through their ideals and glean truths from the art that inspires them—be it King Lear or the New York Giants.

Criticism celebrates and strengthens art. While it is an occupation, it’s a trade that is developed over time with considerable joy and at a great cost. The Critic’s Daughter reveals the inherent challenges in devoting one’s life to art and the work of a critic. Though we bemoan the current state of our industry, things weren’t so rosy in the 1970s either. I wanted to talk with Priscilla about her singular family, the pleasure of growing up submerged in art, shifts within the publishing industry, and what she sees as promising changes in criticism.

*

Lauren LeBlanc: Growing up, not only were you graced with the presence of two remarkably literary parents, but their friends, colleagues, and clients as well. What was it like to be a child surrounded by storytellers and artistic minds? How did it shape your childhood? What did they teach you about the world and the possibility of imagination? What do you most appreciate from your upbringing?

Priscilla Gilman: It was a childhood filled with wonder and awe, merriment and magic, wild, exuberant creativity and incisive, sometimes contentious debates: a tapestry of huge personalities and striking voices. Our rambling, rent-controlled apartment in New York City and our modest Connecticut weekend home were animated by incredible characters from Hunter S. Thompson to Elizabeth Hardwick, David Alan Grier to Fred Exley, Harold Brodkey to Ann Beattie, who came for lunch or dinner, a barbecue for my father’s Yale School of Drama students or a publishing party for one of my mother’s clients, a strategy session with my mother or a poker night with my father.

I’d hear these people discuss current books, plays, and politics, I’d watch as my mother firmly but lovingly chastised a famous writer she represented for falling behind in his or her work and as students from Skip Gates to Mark Linn-Baker clustered around my father, jockeying for his approval, then played jacks with me and my sister, Claire. Claire and I got original bedtime stories from Uncle Bern (Malamud) and Aunt Toni (Morrison), who invented tales from whole cloth for us.

There was a saga that Uncle Bern unfurled over months involving a series of strange birds and their interactions with a family on the Upper West Side; I will never forget when I read “The Jewbird” as a teenager with a shock of recognition! Sesame Street composers made up jaunty jingles for us, Lore Segal dedicated her children’s book Tell Me A Trudy to us, Jill Krementz took our photographs. Well-known or soon-to-be-well-known actors and directors read to us from our children’s books and threw themselves into creating distinctive voices for the various characters. Claire and I were enthralled.

Books were a world as real as the Upper West Side we inhabited, and books gave us access to countless alternative worlds. We probably had 10,000 books in our apartment at any given time. Stacks and stacks, shelves and shelves of them.There was a lot of humor, a lot of playfulness, a lot of fun. But I think the most essential or fundamental thing I learned is that these eminent people were just people! They were brilliant and gifted and revered, but they still had to cope with their children, fend off self-doubt, deal with physical infirmities or emotional frailties. They were often riddled with insecurity.

And some who were the most austere, gruff, or forbidding in their professional capacities were the sweetest and funniest with us. Victor Navasky was a teddy bear, Nat Hentoff was a hoot, John Hollander was a mensch. For them, it must have been a relief to be around us. They relaxed in our disarming presence. They enjoyed meeting our stuffed animals, touring our rooms, and hearing our opinions of books and movies.

LL: Your mother remains a legendary and groundbreaking figure in publishing and your father was a tremendous force in theater and literature. What did you know about the industry that perhaps even the adults in your circle weren’t fully aware of?

PG: I knew that just because someone got great reviews, was highly acclaimed, won awards and received prestigious honors, that didn’t mean their books sold well or that they weren’t struggling financially. I knew that authors who made gobs of money sometimes lacked confidence in the intellectual or artistic merit of their work. I knew that one bad review could sink a writer’s mood and damage his or her well-being for months. I knew about jealousies and feuds between ostensible friends and colleagues. And I knew how fragile success was, how little it took to sink a project, how life-changing one rave review could be.

LL: What did books mean to you as a child? Could you talk about the celebration of books as a child and young adult?

PG: Books Were EVERYTHING. Books in all their stages and phases, forms and guises. Manuscripts, excerpts, proposals. Books in finished copies, books as drafts or pitches or mere ideas. We were brought up surrounded by books. Books were a world as real as the Upper West Side we inhabited, and books gave us access to countless alternative worlds. We probably had 10,000 books in our apartment at any given time. Stacks and stacks, shelves and shelves of them. I could never get enough. I learned to read at a little over three and soon was devouring up to four books a day.

LL: How much of the business side did you understand? Did you even see this as a business? Did your parents’ jobs feel like work or play given the way that their personal and professional lives overlapped?

PG: I definitely did see it as a business and my mother as someone who took care of the business side so the writers could focus on creating, devising, researching, and writing. I knew about things like advances and foreign rights and first serial and movie rights from a very young age. My mom fought so hard on behalf of her writers; she believed passionately in the worth of their work and their right to be fairly compensated for it.

Both of my parents’ jobs felt like work: hard, onerous, meaningful, and vitally important work. I think they both felt they were laboring in the service of literature, books, plays, art. Both saw themselves as being in a kind of service profession. My mother served her writers and their work. My father served the reading and theater-going publics and the playwrights and authors and actors and directors he wrote about.

It is true that many of my father’s colleagues and students became his good friends and many of my mother’s clients became her closest friends. My mother’s editor colleagues like Bob Gottlieb, Alice Mayhew (my father’s editor on several of his books), and Gordon Lish were also dear friends. So that made work more fun and playful for her, I’m sure.

But in the last analysis, she was working under an enormous amount of pressure to deliver for her writers. She still often jokes that she works in “personal service!” And my father took his work as a critic with the utmost seriousness. Criticism was a calling, a noble profession, something that he devoted himself to with an almost priestlike austerity at the same time that he often brought to it a wicked sense of humor and fiery glee in exposing the unworthy, deflating hype, and unmasking pretense.

LL: How much did you understand about the role of criticism? Is there a story of memory you have relating to your father that illuminates that understanding? One from your mother?

PG: In the 70s, a good review in the New York Times, for either a book or a play/musical, could make a writer’s career. By the same token, a pan could close a show and a scathingly negative review of a book meant a much smaller advance next time around and humiliation for the writer because everyone—and I mean everyone—read the New York Times.

I do vividly remember how ecstatic both of my parents were about John Leonard’s rave for Song of Solomon in the New York Times. My mother had represented Toni from the beginning of her career; The Bluest Eye came out the year I was born. Toni was a close friend as well as a client at this point, and my father had always thought her books were just extraordinary and that she needed to be discussed as a major, exceptional, once-in-a-generation writer.

Leonard’s rhapsodic review of Song of Solomon—a review that placed the novel alongside Lolita, 100 Years of Solitude, and The Tin Drum—vaulted her to a new level of recognition and appreciation. My father actually got teary about it and my typically stoic mother screamed! I also remember when it won the NBCC award for fiction and they were both so deeply happy.

LL: What was it like to be a critic in the 1970s and 80s? How much did your mom and dad collaborate in their work? I’m curious how much insight they shed into one another’s careers. Could you speak about that?

PG: My father reviewed some of my mother’s clients! She looked over his contracts; he didn’t have an agent until they split up. But other than that, they didn’t really collaborate in an obvious or literal way. She didn’t read his work in draft or even always in full after it came out. She didn’t ask for his advice on how to pitch projects or sell books. But it was very clear that she treasured his mind and believed wholeheartedly in his brilliance.

He, in turn, greatly respected and admired her work ethic, taste, and deal-making skill and was comfortable in a way that very few men of that era were in taking on a greater share of child-rearing responsibilities so that she could focus single-mindedly on her work. He was totally dedicated to helping her achieve the success he thought she eminently deserved in a man’s world. She in turn fought to help him achieve the recognition and esteem she felt he deserved.

LL: Why did you consider working as an agent?

PG: My mother had always wanted me to try agenting. She said it would allow me to express a wider range of my personality than I could in academia. She’d always say: “you’re a high/low person so you could represent both literary fiction and mysteries and thrillers” and she rightly noted that I am very persuasive. I learned how to be an effective, impassioned advocate from my mother, and that skill served me well as the mother of two children with special needs. But I found that while I loved editing and advocating for my books and authors, I didn’t love the hard-nosed aspect of the business and I also missed teaching dreadfully.

About a year and a half into my career as an agent, my agent and colleague and best friend from Yale grad school, Tina Bennett, sold The Anti-Romantic Child to Harper. I took a six month leave from Janklow & Nesbit to write it and when it came out, my life radically changed in that a whole world of speaking and writing opened up to me. I also began leading book groups and teaching a writing class, then started teaching for Yale Alumni College in 2017.

LL: Now you are a teacher and writer, but also an esteemed critic. What drew you to critical work?

PG: I wrote my first reviews as a graduate student at Yale, in two seminars that required a book review as one of the assignments. I will never forget Ruth Bernard Yeazell stopping me in the women’s room at Yale to tell me that my review of a work on Wilkie Collins was the best she’d ever read by a graduate student. That made an impression! My undergraduate thesis, come to think of it, was also in a way a review of several prominent books of Wordsworth criticism, an extended review that used Wordsworth’s poetry to rebut the critics’ arguments about it. And my Ph.D. dissertation at Yale was on authors’ negotiations with the rising power of critics and criticism in the long eighteenth century.

They both felt they were laboring in the service of literature, books, plays, art. Both my parents saw themselves as being in a kind of service profession.I wrote my first professional, non-academic book review for the New York Times Book Review in 2012. An editor there reached out to me after reading The Anti-Romantic Child and asked me to do a review of a middle grade novel with an autistic protagonist. That led to several more reviews of children’s books for the New York Times Book Review plus a Back Page Essay (remember those?!) for them, a few reviews for the Chicago Tribune and O: The Oprah Magazine, a review of Stanly Plumly’s marvelous The Immortal Evening: A Legendary Dinner with Keats, Wordsworth, and Lamb for the NYTBR, and then a regular reviewing gig at the Boston Globe, where I’ve happily been since 2013. I review between 10 and 20 books a year for them.

LL: How is this period of criticism different from your father’s heyday? Could you talk about the shift you’ve seen in your lifetime and what you think your father would make of criticism today?

PG: One thing that’s helpfully different now is that friends don’t review friends anymore! It was astonishing to me that Anatole Broyard and Christopher Lehmann-Haupt reviewed my father-their close friend’s—books in the pages of the New York Times! We have much higher, more stringent ethical standards now.

The saddest difference is that there is not nearly as much space or nearly as many resources for book criticism. Bookforum’s closing, the number of pages devoted to book coverage shrinking in most newspapers—this would have been very disheartening to my father as it is to me.

The best changes are the greater diversity of critical voices and the greater diversity of work being reviewed. Also, more experimental, unusual, unconventional shows are succeeding on Broadway than ever before, in part because reviewers for mainstream newspapers no longer feel the need to boost the juggernauts and in part because we have more quirky and daring critics reviewing theater. This would make my father very happy.

My father would not at all approve of lay readers’ reviews on Amazon and GoodReads being taken seriously; I on the other hand find those reviews often deeply insightful and moving!

I myself am heartened by the success of crossover critics like Merve Emre, who did her Ph.D. at Yale under the direction of my former colleague Amy Hungerford, and is now a great public intellectual. As the academic job market continues its long, slow-motion collapse, more and more English Ph.D. students are writing for a broader audience. In general, we’re seeing more criticism in major venues, that is, as Ben Brantley described my father’s style, “poised between academic erudition and popular journalism,” and I think that’s a good thing and something he would have approved of.

At the same time, my father didn’t even have a B.A. and he never believed anyone needed to be credentialed to be a great critic. A great critic, he’d say, was someone who could tell the truth about the work in a way that was compelling, courageous, and helpful.

____________________________________

The Critic’s Daughter by Priscilla Gilman is available now via W. W. Norton & Company.