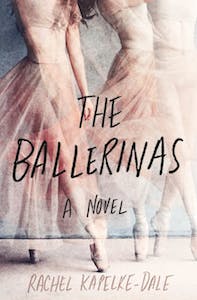

Puncturing a Dream: On the Dark-Edged Fantasy of the Ballerina and Traditional Femininity

Rachel Kapelke-Dale Revisits the End of Her Former Life in Dance

Like fairy tales, most ballet stories are for children. There’s a pleasant symmetry to this, as most classical ballets are themselves based on fairy tales—Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, Swan Lake. Both types of stories are dark-edged dreams that appeal not despite, but because of, that darkness; there is something about that juxtaposition, the chiaroscuro, of them, that rings true to even the littlest of us.

It appeals to me, too. Several years ago, when I sat down to begin work on a novel, I knew I wanted to write about the figure of the ballerina. What I didn’t know, at least at first, was why.

I was 34 when I started writing the story, nearly 20 years removed from my own ballet training, and disturbed that I hadn’t yet achieved my lifelong goal of publishing a novel. Meanwhile, I saw the friends I’d trained with all those years ago beginning to retire. My artistic career was just beginning; theirs was already over.

I was sad; I was worried; I was also, strangely, nostalgic. And I couldn’t figure it out. My own ballet training had ended in a hip injury and the realization that my body wasn’t right for a career onstage. After years of daily classes, I’d embraced my newfound freedom with absolute delight back when I was 15. And yet, somehow, all these years later, I found myself missing the dream.

It’s sold to young girls very early on, this dream of the ballerina. It’s sold to us through the Nutcracker and dolls like the “My Pretty Ballerina,” which I proudly owned. It’s sold through the ubiquity of pointe shoes (my bedroom had a pink-and-cream doorplate with my name surrounded by those shoes and their ribbons) and tutus (the twirling dancer in my music box went without hers after my grubby fingers curiously plucked it off).

It’s sold to us through stories.

As I probed my own nostalgia, I started to get angry, but my anger was wild and unfocused. I didn’t know exactly what I was mad at. All I knew was that I wanted to puncture this dream, to disrupt it. But before I could make any progress on the story itself, I knew that I had to understand who the ballerina was, both to me and in a larger context.

And so, I started looking at the ballet stories I’d grown up with.

Stories for very young children center around the dream itself. They show hard-working girls and women being noticed by authority figures; being plucked out of obscurity, becoming stars. My favorite ballet story was the 1936 Ballet Shoes, the canonical Noel Streatfield story about three orphaned sisters, all with different talents. The youngest, Posy, is the ballet dancer who helps bring money into the family through her performances. Dance teachers and ballet masters notice her, praise her, and make her into a star. Another of my favorites, the nonfiction book A Very Young Dancer, similarly focuses on the life of a ballet student at the School of American Ballet in New York City who has been cast as the starring role in The Nutcracker. She, too, becomes the center of attention: a child among adults, a baby ballerina. Worthy.

That’s how most of us first encounter the literary ballerina: as a driven, not-quite-human character whose passion excludes her from the pain of normal life. She is the chosen one; she is noticed; she is special.

She’s also, almost always, a she. In traditional classical ballets, women are the centerpiece, the stars. The men may have their moments of virtuosity, but, in the end, the beaming woman comes trotting back out onstage to take her place in the spotlight. No other artistic sphere prizes femininity to such an extent. When you’re a young girl, trying to process what your gender means to the world, this is an incredibly tempting milieu: in this world, women are the focus. They can step up into the public sphere and be celebrated.

If, that is, they are a particular kind of woman.

But by prioritizing this vision of idealized, traditional femininity so much, ballet also amplifies the harm that vision can do. Confronted by both internal and external pressures to try to fit themselves into this one particular mold, young dancers have long been particularly susceptible to eating disorders, body dysmorphia, and other forms of mental illness.

This dark side of dance doesn’t appear in most books for elementary-age children. (Neither does the caveat that ballet’s celebration of the feminine is limited to a particular)is reflected in young adult and middle grade fiction as well as on film. In fact, if you’ll excuse the pun, it takes center stage. Center Stage itself, a whirling, frothy ode to dance, emphasizes the stereotypical pitfalls of teen dancers: the cattiness, the competition, the self-loathing, the eating disorders. A few years later, Black Swan would build on these tropes in even darker ways.

By prioritizing this vision of idealized, traditional femininity so much, ballet also amplifies the harm that vision can do.

Neither of these, of course, was the first ballet story to show girls and young women dealing with mental illness. In this, they harken back to the classic 1948 film The Red Shoes, itself based on a Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale. There, her ambition finally outweighing her romantic relationship, ballerina Vicky literally dances herself to death in the eponymous shoes. Don’t want too much, the film—and the fairy tale—warn. The world will turn on you. And then you will turn on yourself.

You’d be hard-pressed, in fact, not to find a YA story about ballet that doesn’t feature either mental illness, eating disorders, or a similarly dark outcome. Why?

Teenagers are drawn to darkness, is the easy answer. But I think it’s something more. I’d argue that these books—The Best Little Girl in the World comes immediately to mind, but there are dozens, if not hundreds—serve as paeans against female ambition. Careful how much you want, careful how much you desire. Writing these books amounts to a warning; reading them involves a kind of schadenfreude. For us, the audience, reading books and watching movies at once lets you into an exclusive world while making you grateful that you don’t have to inhabit it for more than a few hours.

In other stories, the young dancer has grown up. What lies in wait for her? Until recently, not much, apart from a whole lot of regret. There’s Helen Mirren’s ballerina-turned-Soviet-bureaucrat in White Nights, distraught at the reappearance of Baryshnikov, her lost love. There’s The Turning Point, in which Shirley MacLaine is haunted by the fact that she gave up dance to have a baby.

I knew that I didn’t want to write a story that fed into the dream of ballet stardom. I knew that I didn’t want to show young women harming themselves, trapped by their own ambition. But the regret of former dancers appealed to me. It appealed to me as someone who had given up ballet herself, and it appealed to me as a construct I could break down. At its core, this regret was about two things: about aging, and about the persistence of the dream. I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender, Marlon Brando’s boxer in On the Waterfront proclaims. I coulda been somebody instead of a bum, which is what I am.

Don’t we all want to believe that of ourselves?

At 34, seeing my friends retire, I was already feeling terrible about aging, already longing for a time that seemed to have passed me by. (Too bad for me, because that was the youngest I’d ever be again.) That was the kind of ballet story I could get behind.

And so, I began to write about my dancers.

In the first scene I wrote, my three dancers, all in their early twenties, are on a remote beach when one steps on a piece of glass and cuts her foot, badly. Knowing it could mean the end of her career and that medical help is far away, she sews it up herself. Drawing on the story of Emily Brontë cauterizing her own wound after a dog bite without comment, this scene showed me who these dancers were. But more than that, it showed me the extent to which they’d bought into the dream.

As they moved through their narrative, I kept returning to the fictional ballerinas I’d known as a child and as a teenager. And the more I did, the more it became apparent to me that the figure of the ballerina, culturally, is the feminine ideal, abstracted and writ large. She is celebrated, even adored, for her heightened and visible femininity. She is thin and beautiful, elegant and—most importantly—silent and uncomplaining. But she is no more than that.

If you can make people dream in a certain way, you can make them do almost anything.

More than a decade removed from her own dancing career, my narrator, Delphine, returns to the Paris Opera Ballet as a choreographer. This distance allows her to see, for the first time, the structures surrounding the lives of the dancers, the extent to which they’ve been sold a dream which has then trapped them in the performance of a traditional femininity—and which primarily benefits others.

Beneath the greasepaint and the rhinestones, my ballerinas were very, very angry.

In the end, Ballerinas turned out to be about the violence that emerges from the rage of being trapped in someone else’s dream; the fury that emerges once you realize what produced that dream in the first place.

And as I thought about the imaginary ballerinas who filled my childhood, as I thought about the purposes they’d served, I knew that my story would have to both replicate, then pierce, that dream. Its distorted truths, its empty promises. Above all, I knew that it would have to pose two uncomfortable questions to the reader: How can we ever escape the fraudulent dreams of our youth? And what does it look like once we start dreaming for ourselves?

__________________________________

The Ballerinas is available from St. Martin’s Press. Copyright © 2021 by Rachel Kapelke-Dale.

Rachel Kapelke-Dale

Rachel Kapelke-Dale is the co-author of GRADUATES IN WONDERLAND (Penguin 2014), a memoir about the significance and nuances of female friendships. The author of Vanity Fair Hollywood's column "Advice from the Stars," Kapelke-Dale spent years in intensive ballet training before receiving a BA from Brown University, an MA from the Université de Paris VII, and a PhD from University College London.