Public vs. Private: A Bet Between Two Astronauts to See Who Gets to Space First

Nicholas Schmidle on the Jack Fischer and Mark Stucky Wagered a Night of Margaritas

Mark Stucky was about to lose another race. This one was personal.

In 2009 Stucky and an Air Force lieutenant colonel named Jack Fischer made a wager over who would get to space first. Stucky had just joined Scaled (which would be bought out by Virgin Galactic in 2012), and Fischer had just joined NASA. The victor would win an evening of margaritas and tacos at Domingo’s, a Mexican restaurant near Edwards Air Force Base. It was a good bet: the battle of publicly versus privately funded space travel, reduced to a duel between two old friends.

When they first made the bet it looked like Stucky would win. NASA was sclerotic, and Fischer knew it. It pained him to witness an agency that had once inspired the world become “plagued with dated paradigms, abysmal acquisition performance, a growing list of hazards,” and an ever-shrinking budget. The thrill was gone—the Shuttle program was on the ropes; the US government was about to outsource its launch capability to Russia, a longtime foe; and Americans couldn’t have cared less. It was a tragic tale of apathy eroding imagination.

Stucky may have won had SpaceShipTwo not crashed and set them back, but now it was up for grabs.

Two years after the crash Fischer emailed Stucky and said he was scheduled to launch in about a year on a Russian rocket to the International Space Station. It was July 2016; Stucky thought Virgin had a fair chance of being spaceborne by then, too.

“The flight/race/bet is ON,” wrote Stucky. He and Fischer each promised to carry an item into space for the other person; Stucky provided Mike Alsbury’s old name tag, which read mini. (Alsbury was the younger of two pilots at Scaled named Mike.)

But the Russians had stayed on schedule, while delays added up and ate away at SpaceShipTwo’s progress.

In March 2017, a week after Stucky got home from NASTAR, Fischer was on his way to Moscow. It burned Stucky up—how Virgin had squandered all that time, but also how America was reliant on Russia to get NASA astronauts into space—a sad sign of national decline. Part of Stucky was jealous of Fischer and wished he was the one about to squat into that old Soviet workhorse, the Soyuz. But another part of him cringed when he saw Fischer posting pictures of himself on social media from a press conference held in front of Lenin’s statue, a prop for Vladimir Putin’s PR machine.

It was a good bet: the battle of publicly versus privately funded space travel, reduced to a duel between two old friends.

Fischer abided by Russian traditions, and they had plenty; anything Yuri Gagarin had done, he did, too. During training, Fischer bunked at Star City, where he ate goulash to sustain him through long days learning Russian and the intricacies of the Soyuz. After Moscow, he flew 1500 miles to the spaceport in Kazakhstan—an American marooned on the dreary steppe. How could his countrymen know that he was about to blast into space when he did so from a place so remote the Washington Post said it “muffled their launches to the point of obscurity for much of the American public”?

On April 20th an orthodox priest blessed Fischer with holy water before Fischer boarded a bus, just as Gagarin had. The bus made the short trip to the pad, and on the way the bus stopped and Fischer got out, like Gagarin, and peed on the rear tire, like Gagarin. “It’s an entire flow of tradition,” said Fischer. He decided it was better to go with the flow than resist. “You could not do it, but do you really want to take that chance? Like, for real? I’ll pee on that tire. Why not? Just in case it helps.”

He climbed into the capsule and listened to a playlist he made. It included “Danger Zone” and “Fly Me to the Moon,” his wife’s favorite song. He hung a talisman, another Russian tradition: a felt sun with multicolored rays, the logo of the Houston hospital where his teenage daughter had been treated for a rare form of thyroid cancer. When the rocket ignited, the capsule rumbled to life, like “a sleeping dragon waking up in a bad mood,” as another astronaut put it. The Soyuz boosted Fischer into space, and six hours later it docked at the ISS.

Stucky sent me a text message that afternoon. It was all over, he said: Fischer won the bet. And while Stucky hated to lose he was happy for his friend and pleased to know that now there was a memorial to Alsbury floating in space.

“Mini’s name tag and photo are now in orbit,” he said.

*

Stucky called his old friend, Jack Fischer, to book dinner: Stucky was ready to settle his debt.

They decided on a weekday evening at the end of January. Fischer had plans to be at Edwards that week. After work they could meet at Domingo’s, just like old times. Word got out. Others asked to come. They soon had reserved half the restaurant.

Stucky and Agin arrived early. Stucky hadn’t been there in years, but Domingo’s looked the same as ever—pleather booths, test pilot memorabilia covering the wood-paneled walls. Stucky smiled at the silly photos of astronaut crews wearing sombreros, fake mustaches, and burlap ponchos.

Fischer came in with a handful of senior military officers. When he came back from space he had options. Peggy Whitson, a fellow astronaut, was about to retire and go on a lucrative speaking tour. Fischer could have done that, or he could have gotten in line to go back to space. Instead, he left NASA and returned to the Air Force, to help set up the Space Force. Fischer was a warfighter after all, and space travel, despite its comradely and humanistic overtones, had always been a quest for military dominance. “Science happens not because governments care about science. Science happens because governments care about other things that need the science,” said astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson.

A waiter took drink orders.

Stucky got a margarita. Fischer asked for the same, but he wanted the big one, the one they served in the stemmed fishbowl glass. Fischer had fond memories of this place. When he was coming up it had been the meeting spot for testers.

When the rocket ignited, the capsule rumbled to life, like “a sleeping dragon waking up in a bad mood,” as another astronaut put it.

Domingo Gutierrez, the owner and the town’s honorary mayor, made the rules. “At one point when we were testing the Raptor”—the F-22—“he wouldn’t let you in if you didn’t have a SAP clearance,” said Fischer. SAP stood for special-access program, the peak of the top secret pyramid.

Fischer recounted the time he and his wife drove their RV off base, parked at Domingo’s, drank far too many margaritas, slept them off in the RV, and then drove back onto the base the next morning. He considered himself an authority on Domingo’s. When the general with whom Fischer was traveling asked about the seafood, Fischer suggested the chicken: “We’re in the middle of the desert, sir.”

They were drinking and laughing and sharing fond memories of acquaintances who had died in the line of duty when Steve Rainey, a gravelly-voiced F-22 test pilot, tapped a knife against his glass. Rainey stood up. He was the one who had provoked the bet, and so he should share the backstory.

“Once upon a time, there was this guy named ‘2Fish’ Fischer, better known as ‘4Fish.’ And he wanted to be an astronaut and somehow he made it. We were at SETP and I guess I threw down a bet: it was based on NASA’s performance at the time, and Forger was with SpaceShipTwo, and I said, ‘Forger, buddy, you’re going to beat 2Fish to space.’”

And yet, he said, waving his hand at Fischer, “You won.”

Fischer stood—a solid man with a disarming smile. Yes, he said, he had technically won the bet. But, “Forger won by an epic margin of classy awesome.”

“The Chuck Yeager of the 21st century!” Rainey said, of Stucky.

Stucky shrank a little in his seat, proud but also a bit embarrassed to be feted in such esteemed company; Rainey had more hours in the F-22 than almost anyone, and Stucky considered Fischer one of the finest test pilots of his generation. Dissembling, Stucky remarked that he had been in space for about five minutes, whereas Fischer lived there for four months.

“It took me eight minutes just to get to orbit!” said Fischer.

But Fischer and everyone else in that room knew the truth—how not all flight-test minutes were created equal, how one minute at the controls of an analog rocket ship could say more about a pilot than thousands of hours in another vehicle, how the margin of error on SpaceShipTwo was nearly invisible, and just how extraordinary Stucky’s experience and successes had been on that ship, and others.

Stucky stood beside Fischer with his margarita glass aloft.

“Test Gods!” Rainey hollered.

__________________________________

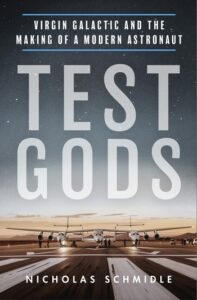

Excerpted from Test Gods: Virgin Galactic and the Making of a Modern Astronaut by Nicholas Schmidle. Published by Henry Holt and Company May 4th 2021. Copyright © 2021 by Nicholas Schmidle. All rights reserved.

Nicholas Schmidle

Nicholas Schmidle writes for the New Yorker and is the author of To Live or to Perish Forever: Two Tumultuous Years in Pakistan. His work has also appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the Atlantic, Slate, the Washington Post, and many others. Schmidle has been a National Magazine Award finalist, a two-time Livingston Award finalist, and winner of a Kurt Schork Award. He is a former fellow at the Institute of Current World Affairs, the New America Foundation, and the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and a former resident at the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Center. In 2017, Schmidle was a Ferris Professor of Journalism at Princeton University. He currently lives in London with his family.