Private Lives, Public Faces: On What’s Revealed by Hannah Arendt’s Archives

Samantha Rose Hill Considers the Importance of Marginalia in the Writing Life

Libraries, as Hannah Arendt well knew, can be dangerous places. In 1933 she was arrested by the Gestapo one afternoon leaving the Prussian State Library on her way to meet her mother for lunch. Her friend, Kurt Blumenfeld, had asked her to collect anti-Semitic statements from newspapers, journals, and speeches for the German Zionist Organization. At the time, this was an illegal activity the Nazis called “horror propaganda.”

The collection of materials was to be sent to foreign press offices and world leaders, to show how dire the situation in Germany had grown, and used at the 18th Zionist Congress that summer in Prague. For several weeks, Arendt sat in the library sifting through newspaper articles and statements from all kinds of professional clubs and organizations. And then, one afternoon, as she was leaving, she was arrested. A librarian had reported her unusual reading activity to the Gestapo: What use does an academic have with so many newspapers?

Arendt was detained for eight days before being released by pure luck, as she would later say, knowing full well what was happening to other people who had been arrested, disappeared in cellars, murdered, and transported to camps. The night of her release, she gathered her friends and drank until the early hours of the morning. As the sun began to rise, she and her mother Martha fled, taking little with them.

Among her belongings was a folder that contained her birth certificate, her diploma from the University of Heidelberg, a self-portrait titled The Shadows, a copy of Love and Saint Augustine, the manuscript for Rahel Varnhagen, which was to be her habilitation (second book for a teaching position in Germany), marriage documents, and 21 poems she wrote between 1923 and 1926. She held on to these private artifacts of her experience and inner life during nearly eight years of exile in Paris before escaping to the United States, which are now neatly tucked away in Container 79, Folder “Miscellany: Poems and Stories, 1925-1942 and Undated” in the United States Library of Congress in Washington, DC.

Etymologically, an archive “houses.” It is a kind of dwelling space. When I first entered Hannah Arendt’s archive at the Library of Congress in 2010, I felt like I was trespassing into somebody’s home. I kept waiting for somebody to come and take the folders away from me. There was a sense of transgression in touching those private things, which spend their time away from public sight. It is no wonder that our modern conception of pornography was born in archives, in those windowless backrooms where the illicit treasures of Pompeii were held.

Historically, the archive has negotiated the line between public and private life, deciding which materials should be available for public access. And for a long time, they were reserved for the few who could afford such pleasures. (Many still are.)

In The Human Condition, Arendt talks about the need to separate the private life of the home from the public realm of human affairs. One needs a space for appearance in the world, and one needs a space to retreat from the glare of public light to be alone with themselves. The archive complicates Arendt’s distinction. As a dwelling, it is a private space that can be accessed by the public, sometimes.

As institutions archives become part of a national mythology, helping to make the narratives we live by. Archives keep the records. For Foucault, archives transformed a collection of texts into a set of relations. Tracing the root of archive to the Greek arkheion, Derrida shows how archive refers to the arkhē of the commandment. Archons were the lawgivers, citizens who possessed the public authority to make laws, and they kept their official documents at home. Archives were established by the powerful to guard their social and political positions in society. One need look no further than the librarian who reported Hannah Arendt for reading too many newspapers to begin to think about the relationship between archives, libraries, and the state.

While there is much to lament about the ways in which digital technology has transformed our daily lives, one benefit has been the opening of previously privately held collections: Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium, Walter Benjamin’s Papers, The Nietzsche Project. And now, for the first time, Hannah Arendt’s archive is fully available for public use by anybody who has a computer.

One needs a space to retreat from the glare of public light where they can be alone with themselves.

Since 2001, Hannah Arendt’s papers have only been partially available digitally, and fully available in three locations worldwide: The Library of Congress in Washington, DC (where most of the physical papers and documents are held), the New School for Social Research in New York City, and the Hannah Arendt Center at the University of Oldenburg in Germany. The papers include over 25,000 items, about 75,000 digital images, and contain correspondence, articles, lectures, speeches, book manuscripts, transcripts of the Adolf Eichmann trial proceedings, notes, notecards, teaching material, syllabuses, and family papers. You can even look at an echocardiogram of Arendt’s heart.

When I first visited Arendt’s archive, I worked my way through her papers alphabetically, following the finding guide the aide at the desk handed me when I walked in. In “Correspondence Folder A-B” I read her letters with W.H. Auden about friendship and forgiveness, her fight with Theodor Adorno about the publication of Walter Benjamin’s papers, which Arendt had carried across the Atlantic when she escaped Nazi Europe, and I read Walter’s Benjamin final letters to Hannah Arendt, which included a hand drawn map of Lourdes, and Benjamin’s last work, written on a stack of colorful newspaper bands, titled, Theses on the Philosophy of History.

There are fights with publishers, letters of recommendation for graduate students, stacks of notecards for lectures, legal documents from lawsuits, day planners with shopping lists, and birthday cards. In Hannah Arendt’s papers, you will find two essays she wrote in German for Walter Benjamin. The drafts of her response to Gershom Scholem after he told her she had no love of Israel, which judging by her hand edits she struggled to write.

You can read a card from Thomas Mann, previously unpublished. There are four drafts of The Life of the Mind, course lectures on Plato, Aristotle, Nietzsche, Kant, Spinoza, Hegel, Marx. You can look at her drafts of “Truth and Politics” and “Lying in Politics.” You can see her mother Martha Cohn’s papers from Nazi Germany and a Kinderbuch (a record of Arendt’s childhood). Among these files you will also find a record of friendships, stories untold. Arendt’s correspondence with Randall Jarrell, Roger Gilbert, Uwe Johnson, Robert Lowell, Ralph Mannheim, Dwight Macdonald, Norman Mailer, and Paul Tillich. With the opening of Arendt’s archive there is no shortage of new stories than can be told. “Let us not begin at the beginning, nor even at the archive,” Derrida wrote.

Before Arendt began doing political work for the World Zionist Organization in the Prussian State Library, she was researching her book, Rahel Varnhagen: The Life of a Jewess—a work that was interrupted by the Second World War, arrest, and internment. Editing the book after the war, Arendt said that in Rahel she had found her “closest friend, though she had been dead for some hundred years.” I’ve often thought that when Hannah Arendt bequeathed her papers to the Library of Congress she imagined somebody might find a best friend in her someday.

*

The newly digitized Hannah Arendt papers can be found here.

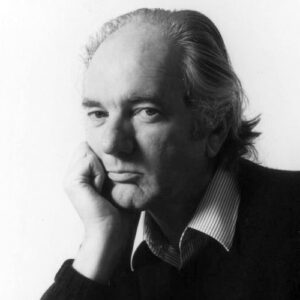

Samantha Rose Hill

Samantha Rose Hill is the assistant director of the Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities and visiting assistant professor of political studies at Bard College. She is also associate faculty at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research. She is the author of a forthcoming biography on Hannah Arendt, and Hannah Arendt’s Poems.