Jaquith House was more a compound than a house, although there was a house at the center of the grounds, a large white mansion in clapboarding. A farmhouse with a long front porch and two upper balconies. A gabled turret held sentry over the drive, with tall French windows and a small enclosed deck.

The driver let me out onto the gravel and went to seek my new keepers. He was right, at least I had my looks. My ever-mutable container, my compact symmetrical spirit vehicle, nothing wasted, nothing lacking, like a dressmaker’s dummy. I had my features, which had not aged out, teetering on the cusp, but as of yet, still featured. And I had my costumes, my rich wealth of carapaces in several large valises, my wigs and accessories, my suits, my sock garters, corsets, cummerbunds, caftans, smoking jackets, leotards, cufflinks. My wardrobe had always been my passport. I thought of it constantly but spoke of it to no one. I believed that everything could be controlled with the proper attire. For arrival at the sanatorium, an ensemble of nouvelle vagaries: a square-necked cocktail dress, cut low, matronly sling-backs, my hair dark and shaped, Cleopatra liner. I don’t know where I thought I was going; to my last year at Marienbad, I suppose. The mind conjured only the settings of old films that no one watched anymore. I could no longer control the phases of my mind, but I retained an arsenal of imagery to impose composure on my general physique.

I made for the large front porch of Jaquith House, hanging ferns and trailing geraniums, a basket of woolen lap rugs, and a line of wicker chairs, well-appointed on a glittering pond. The air was crisp for August. For a coast, it was lacking horizon. I was born on a coast, quite a different one, but one that nonetheless had taken. Me. Yes, I was a coastal tramp, but there was no coast in particular that claimed my heart above others, and the promise of coastal proximity had been the final piece in my resignation to try Jaquith on for size. I am a vagabond, and always have been—whatever I do, I do with location in mind. I had little interest in rehabilitation, I told myself, but even I could no longer tell when I was lying. I wanted to sleep again, or if not sleep, I wanted to enjoy the night hours, that much I knew. And I wanted to return to my strong silent type—this sound of a voice blithering on, alien to my ears, had also strained my vocal cords. My voice finally had the breathy basso notes I had been feigning for years, somewhere between Lauren Bacall and James Earl Jones. My voice had been made legitimate and, in this way, was all the more upsetting. Perhaps this was the true fear for my employers, I suspected, that my breakdown was not an aberration of self but a galvanization of self, an excess of self. An excess of Helena, which no one, least of all me, wanted.

Assessment was required, a specialist to assess the actual damage and then weigh the financial pros and cons of my resurrection.

Any coast in a storm, then, and onward to the sanatorium. But we were in the woods. I couldn’t even smell the sea. A soft calypso recording floated in the air, and the front door seemed not only locked but permanently secured.

Beyond the western lawn was a garden plot and a fruit orchard in neat rows. Beyond that, the surrounding woods. A sudden grinding of an engine within the pond spit up a geyser, rattling the placid surface.

This place is a fraud, like me. Wrongly placed in time. I was already working on my dialogue for the doctor. The studio will have had their say, now I would have mine. I had imagined a surgical strike: I confess wrongdoings, he absolves me of my crimes. I retire somewhere unobtrusive and go about the rest of my life in quiet daily repetitions: small tasks each morning, like carving a wooden spoon or embroidering a tea towel. No more screens or lenses. Screens and lenses would be forbidden. They were what got me into this mess. On this we could all agree. The specifics of my wrongdoings were still fuzzy. Out of focus. For me, it was a matter of subjectivity.

I set out around the house. A stone walkway through hydrangea and rhododendron and other threatening, tufted shrubs. The path itself was so overgrown and wove through the pendulous pink blossoms. In a turret room high above me, the French windows swung shut, and I heard the click of the latch. Marimbas and steel drums of a jaunty calypso soundtrack piped in at intervals.

It was a festive scene this little Jaquith House piazza. Several discreet patio tables in wrought iron scattered the court, flower-garden borders, tiny ponds, overhanging sun umbrellas in gay colors. Paper lanterns stretched between the house and an enormous barn. It was all trying a little too hard.

I saw the backdoor of Jaquith House and knew at once that it made its front its back and vice versa. The calypso music shouted now from an imitation rock in the herb garden.

Inside a lit paned-glass veranda, an older man in a dark sport coat with white piping and a knotted neck scarf tapped out his pipe on a saucer. He waved at me from behind the glass. I waved back. Hanging on the double doors was a cheerful sign in rope and plaster, which announced, in barely legible cursive, “You Are Most Welcome at Jaquith House.”

*

And so it begins, I said.

Helena, I am so delighted to finally meet you! I have been a devoted fan.

Doubtful, doubtful, I said or thought, and with more enthusiasm, Dr. Duvaux, I presume!

He was the spitting image of Claude Rains, in his venerable years, an upsweeping quiff of gray hair, a round and solemn face, a practiced theatrical voice that belayed an underlying impediment. We were crossing the floorboards of the common room. A large, open fire pit failed to burn on its elevated slate platform. Above it a copper hood stretched rigid and gleaming for several stories.

Entirely at your service. As are our expansive facilities and our extraordinary staff. And yes, truly, Helena, I have seen all your films. I so look forward to working with you.

Yes, working. In your expansive facilities, with your expansive staff.

In situations of psychic exhaustion, Dr. Duvaux said, it is always the correct and best method to surround the sufferer only with individuals who are properly trained in therapeutic recuperation.

The room was cavernous and empty. The doctor gestured to a low bench near the smoldering hearth.

Sit with me, won’t you, for a few minutes? Everyone at Jaquith house is a welcome guest, he said. But, also, everyone at Jaquith House is specifically trained. All our aides-de-camp are top in their respective psychiatric branches. Even our housekeeping staff is highly trained in the specifics of therapeutic recuperation.

I am a victim of psychic exhaustion? I asked.

You are a habitué. In the sense that you frequent that locale, but you do not yet inhabit that locale. Our job will be to stave off—

Let us get something straight, Doctor. Whatever the studio wants from me, I doubt they will get, ever again.

And what is it you think the studio wants from you, Helena?

To finish something I started, possibly. Something that may have incurred considerable expense. Or something they hope will recoup them financially. Then to let me drift. To cut me lose.

You can’t mean the film—

No, not that one. An option. Oh, what a misleading term. This option has no option for me, that is certain, it was the beginning of the end: I can see that! Listen, Doctor: I am beyond rehabilitation.

I am inclined to think your studio thinks, well, that you have been a brilliant asset, and could be again. Do you want to tell me more about this option, as it were, Helena?

A collaborator, possibly locations. I don’t know what they’ve dumped in already, maybe nothing, maybe something. I relinquished control, but they have something up their sleeves. But I had given up on it even before the… the accident… Listen, Doctor, I’m not going to talk about that.

The accident, Helena? Or the option?

Neither. I’m talking about other wrongdoings, of which there are many, I admit, but I won’t apologize to the studio—

Oh, no, of course not. I think there’s been some confusion. My understanding is that your studio just genuinely hopes to help you find some sort of balance, to pick up the pieces. And I hope that is true. I don’t like to enter into these kinds of arrangements under false pretenses.

Ha! The studio is nothing but false pretenses.

We are not here for the studio, are we? We are here for you and whatever it is you are seeking. There was an accident on one of your sets, Helena, and I know you suffered a great loss.

It was part of a larger problem, obviously.

Yes, we don’t have to go into it just yet.

I thought I would go back to work immediately after the accident. But there was no work to go back to, as it turned out, not on that film anyway. I had come almost straight on from the hospital in Rio—why they had flown me all the way to Rio, I have no idea. Perhaps they thought it was an excellent hospital. It was in fact an excellent hospital. They kept me for a few weeks after setting my bones and sewing up my hand—you see, I’m now missing the littlest finger. A minor sacrifice, I know.

Ah, trauma to the body! No, we won’t discuss it yet, not yet.

I don’t mind. Actually, not at all. It looks like a proper claw, like the talons of an eagle. Then they kept me in a deep sleep.

The studio?

The doctors in Rio. I could remember faces pacing through the room, the sounds of the pumps and the monitors. There was an endless stream of identical attendants, the language is like a blend of French and Spanish, both languages I know well, but still, to me, untranslatable. That period was glazed. After my release, they gave me prescriptions to help overcome the pain of the injuries from the accident, and these pills washed me in a pleasant calm and loosened my damaged limbs, truly, but made it possible to lose track of most of my mind. The studio had cleared the location of my film Sanguine Season, I was told, completely obliterated all traces of it. I was flown home. Home? Where was that? A sun-streaked megalopolis on the edge of a cold ocean? I hadn’t been there for more than a few weeks at a time for years. My bungalow is rented. I got a hotel room that was very far from everything. With a little money, a couple of midcentury replicas, a cocktail cart, a little dog in a sweater: it’s possible to live like you are stuck in a time flow, don’t you think, Doctor?

Selectively, I suppose. If you turn a blind eye to the difficulties, the drudgeries, the atrocities of the past. And, I would think, a blind eye to the speed of the now.

Sanguine Season. My last film. Or my almost last film. They got me a driver, and I went into the studio. They call it a studio, but it’s just a corporate building, a bunch of conference rooms full of silver-haired gents dressed like boys in T-shirts and sneakers, staring into their screens or forcing me to stare into screens, middle-aged men in crumpled-casual resortwear, in athleisure, phoning me from the golf course, from the tennis court, from inside a barometric chamber, middle-aged men, sometimes one woman, a woman but indistinguishable, phoning in to decide my fate. You see, they had to do something with me, while the insurance investigation went on.

What did they say to you?

They were ready to find a new balance, they said. They didn’t even mention Corey—but what was the point after all?

A tremendous loss, Helena, a brilliant actor cut short in his prime of life. You two were very close, I know. You did quite a few pictures together, didn’t you? I think I have seen them all.

They didn’t even mention his name. They just got right into it: Helena, they said, we’ve seen the paperwork, they said, let us reassure you at once that we don’t take much stock in documents. But you must know that it will not be possible for you to continue the film as… that film… in Guaporé. Sanguine Season is just not a candidate, do you see? On the other hand—Madrid Plays is. And it was your option, remember, your idea. And we love it! Once we sort out this insurance business, a little PR spin work, we’ll get you back in the director’s chair, and we think: really, Helena, we always thought, this next option is really the one. Or possibly the many—who knows, you might want to serialize! If you were to stick it out here in the studio, in the meantime, you would have time on your side. This town is a sandpit of disregard. Sure, there seems to be silver-screen nostalgia on every street corner, and the mansions and the aging celebrities, but the truth is this town swallows up everything for better or worse.

This town? There are no more towns. Everything is everywhere at once.

We think if you can just be agreeable about this, we can salvage you, get you back to working, it’s a simple process, we get you some help, when you’re ready you get back to filming—

The Doctor interrupted me: What did you say to that offer? he asked.

I said yes. Good. It wasn’t Guaporé, I said. It was Iténez, but what difference did that make, the borders between countries, different languages, Sanguine Season was gone, obliterated, my entire production suspended. Fine, I said. Whatever you want, I said. They hadn’t expected that! Compliance. I was dead set to be compliant. I comply, I said, and I flashed my bird claw. And they were relieved to hear it! To be perfectly honest, they said, we are incredibly relieved to hear this, Helena. Incredibly relieved. And you don’t have to let this feel like a blow.

I was trying, Doctor. I told myself, I was a new Helena, a compliant Helena. I was no longer Helena the tyrannical, Helena the hysterical. Those hard-won years of control on the set, the manipulation, the violent rages, what use would they be to me now in an era where control is passé? Hierarchies, Doctor. Obliterated. You see, the details, can you hear me?

Perfectly. I hear you perfectly. And so that is how you find yourself here, Helena?

I suppose so.

Do you see this as the studio’s way to phase you out or to bring you back to the fold?

I’m not sure. I’m not sure they are sure. I think they are buying time.

And what about you?

Me?

What about your future? Your future in film?

Future?

You gathered a very faraway look at that moment—as though you were in a distant garden, the doctor said.

And so I have been, I said, a kind of garden. But now I am here.

Oh, and I am so glad. We’ll return to this conversation when you are feeling more settled. As I mentioned, everyone here at Jaquith House is especially trained. He suddenly produced a pamphlet with the floor plan.

There aren’t any patients then, Dr. Duvaux?

Helena, I think you will find that even our sufferers are apt in their sensitivities, and that our aides-de-camp are investigating their own psychic crenellations via their practice. Yes, we are a very special collective, said the doctor.

Doctor, I’m not sure I will show the same aptitude for sensitivity that your other inmates seem to share. I am not a known sensitive.

I think it is evident that you will and that you do. It is evident in your artistic craftsmanship, Helena. Many of us are great fans of your films, he said.

I looked around me. There was only the doctor and myself. There was no one else. No one sitting anywhere in the colossal common room, with its gleaming pine floors and Persian rugs, there was no one around the open fire, no one in the table game area or the tea nook, no one seated anywhere, despite a number of plump, chintz possibilities. No one in the rattan fanback chairs or in the tartan-covered wing chairs, no one stretched out on the wooden benches, no one swaying in the highly symbolic rocking chair. It was an empty set.

Many of us, Doctor?

Helena, I thought it best for your first night to keep things very quiet. But I think you’ll find a small but lively crowd gathered in the grand dining room just beyond those wooden doors. You must be exhausted. But they are there, if you are ready for them. Shall I take you through? he asked.

But suddenly, I could not fashion a reply.

__________________________________

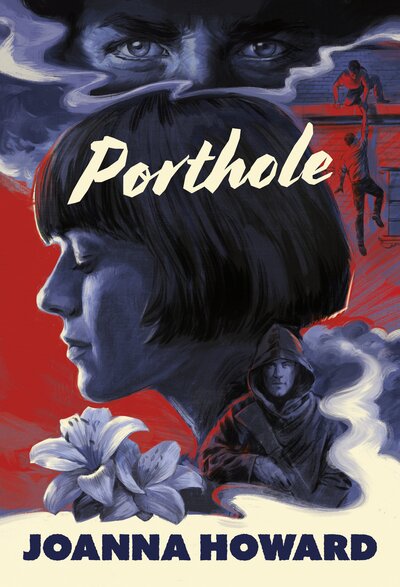

From Porthole by Joanna Howard. Used with permission of the publisher, McSweeney’s. Copyright © 2025 by Joanna Howard.