Portals, Vehicles, and Vessels: How Folklore Holds the Weight of Cultures in Flux

Thao Thai Discusses the Power and Creative Use of Mythology with Anna Kovatcheva, Alice Evelyn Yang, Ryan Collett and Sarah Hall

Recently I’ve been thinking about how writers work in a time of extremes and how our work has begun to reflect this tension. On the one hand, readers and writers are tugged toward the distant future, a world of climate catastrophe and tech transformations; on the other, we’re looking back at texts written centuries before, hoping to illuminate the path forward through the lanterns we’ve been given. We stand positioned somewhere in the middle of it all, watching the collision of past and future. This collision is especially fascinating when we consider folklore, a living and relentlessly malleable discipline.

In my debut novel, Banyan Moon, I structured the narrative around a central piece of folklore about Chú Cuội, the man in the moon. While the folk tale was important to the book, what struck me wasn’t the folk tale itself, but its ability to become a threshold into the past, a way for writer and reader to join conversations begun years before. Similarly, my upcoming novel, The Seekers of Deer Creek, finds its way through personal folklore, the unstable family mythologies we disrupt through our engagement with the past. Folklore is about alteration and collaboration; it resists clear interpretations. But, of course, as writers, we must try to make sense of the tools we’ve inherited.

This past winter, a time rife with lore, I had the privilege of speaking to four fantastic writers about the role of folklore in our work. Below, Anna Kovatcheva, Alice Evelyn Yang, Ryan Collett, Sarah Hall, and I discuss “thin places,” doppelgangers, AI art, and more sprawling thoughts on storytelling.

—Thao Thai

*

Thao Thai: Last fall, I gave a talk on folklore at a literary festival and remember that, in preparing for the talk, I circled around many ideas about what folklore means to me and my storytelling. Folklore is such a broad concept and genre that it feels impossible to limit its definition. I eventually landed on the description—less a description than a notion—of folklore as a culture’s urge to preserve itself. That sense of collaborative continuity makes me think of folklore less as a static artifact and more of a borderless space of the imagination, into which we can all pass at will as travelers and co-architects. I’m curious: how do you each conceive of folklore? And did you work with a dominant piece of folklore as a throughline in your novels or did you employ several, as a sort of storytelling pastiche?

Anna Kovatcheva: Recently I exchanged emails with a folklorist whose scholarship helped inform my first novel, which is rooted in Slavic vampire and slayer lore. I wrote to thank him for his work, which I’d referenced often while writing, but somewhat sheepishly noted that I’d also taken many liberties. He wrote back: “Please note that that is how folklore works: taking liberties.”

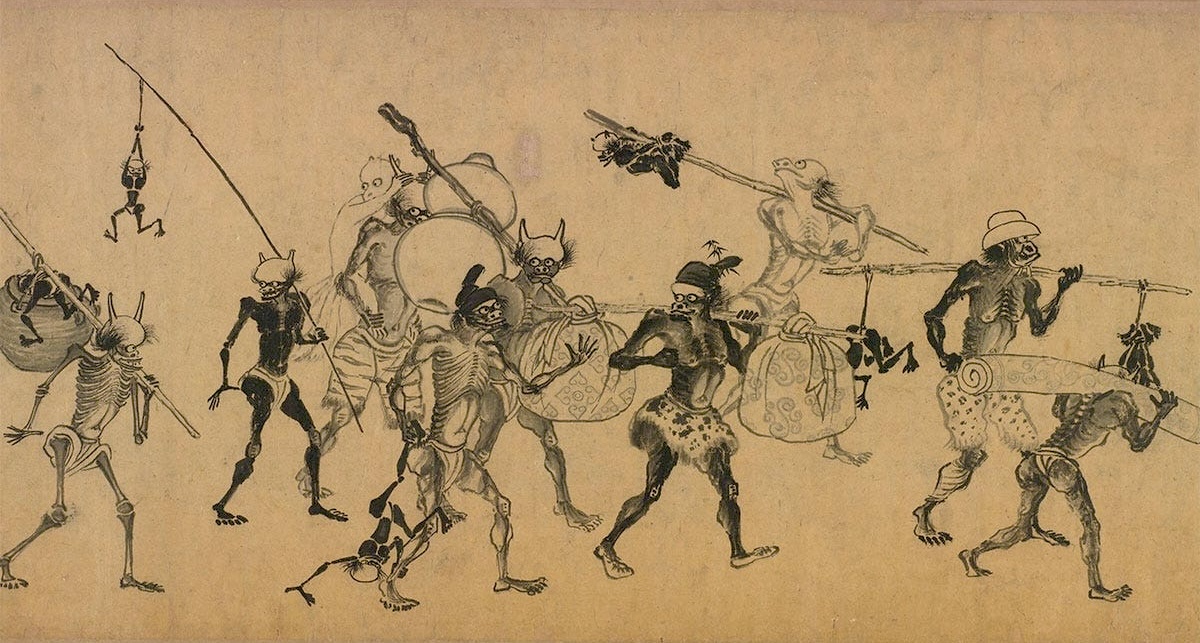

It’s unsurprising that when faced with the challenge of relaying information over thousands of years, folklore and myth emerge as possible answers.

Thao, I love your description of folklore as a place we can all pass through, rather than a parcel enclosed and owned. I think that’s what appeals to me about it, too: that it is a collective practice, and one that bends to its storyteller’s needs. Early vampire lore was instructive. It helped explain the inexplicable—crop failures, premature deaths—and gave advice on how people could fight back against the unseen, or at least how they could comfort themselves. Now I’m borrowing pieces of those same stories to entertain, and to talk about women’s agency and community, and of course they’re malleable enough to support that, too.

Sarah Hall: It’s difficult to define folklore, but I suppose I think in terms of a similar liminal and creative space, where there’s a conversation between All People in relation to stories and art, color and imagination. I’m trying not to get too hung up on art and artifacts here as I have an Art History degree and studied folk art, so objects like treen and barge-ware and quilts always come to mind! I’m interested in the class aspect of the folkloric too—there has been such a hard border between “fine art” and working class arts here in the UK over the centuries, with the latter considered naive, culturally and historically less significant, and really not being given its due. When I wrote a novel about tattooing over two decades ago, it still felt a little like that.

Happily, it’s all breaking down now as new generations of makers and practitioners demonstrate the skills of their occupations and how making reflects society. For me, folklore started right back at school, when our junior headmaster used to sit and tell us tall colorful tales, oral Cumbrian legends and ghost stories, which could be augmented and added to in the telling. For Helm, I leaned into that principle—mutable narration as its own truth, the fantastical, the vibrant and the antic as authentic. I also had in mind Shakespeare’s Puck, a kind of spritely Nature voice, something earthy if not classical. I’ve always worked with environmental themes but personifying an element was a way of reaching back towards the ancient character of the Green Man/Woman.

Alice Evelyn Yang: For me, this emphasis on evolution and preservation was most present in a book I read for university: The Kingdom of This World by Alejo Carpentier. Carpentier wrote a narrative imbued with lo real maravilloso, or the “marvelous real,” one of the craft predecessors to what is now known as magical realism. In the work, traditional folklore and marvelous, uncanny incidents are often the sites of resistance against colonialism or enslavement. This book shaped my understanding and use of folklore as a space of critical fabulation and a tool to examine and relay history through a postcolonial lens.

I like Anna’s description of folklore as a device from the past used to explain the inexplicable. In my novel, folklore is the vehicle through which generations and ancestors can commune with another: the stories and relics of those myths as an inheritance—both the Chinese folklore of the colonized and the Japanese folklore of the colonizer, whose mythical figures colonize Manchuria at the same time as its armies.

Ryan Collett: Thao, I like that term you’ve used, “collaborative continuity.” It’s a great distillation of what folklore should do. For me, the idea of folklore actively encourages us to be less precious with our myths and legends, which is antithetical to how we’re made to believe storytelling should be today. Modern considerations like “canon,” “tropes,” and “shared universe” are wildly self-censoring maladaptations as a result of art’s continuing corporatization and we should all look to folklore as a guide for how to respect our creative impulses, not hinder them. I first linked the George and the dragon myth to my novel George Falls Through Time pretty early on in the writing process, largely out of ignorance (i.e. curiosity) and clever convenience. Because it’s such a universal story told in some form or another across multiple cultures, I felt immediate ownership over it, just as strongly as any other person should feel complete ownership over it—and there’s the beauty of folklore. There’s no copyright contingency telling you the dragon needs to have wings or not, or George should be English, French, or Turkish.

TT: Let the dragons be what they will! What are the folklore themes or foundational folk tales you keep returning to? For me, it’s Perrault’s Bluebeard tale, but I’ve since encountered other iterations of this same story. Locked doors, bloody bits in trunks, deceptive lovers with ill intentions. My mother told me a Vietnamese version when I was a kid (not a light bedtime story!), so my mind snagged on it early and couldn’t seem to let go. For me, that says something about my preoccupation with monsters-in-disguise and the agency of women in both uncovering and conquering violence. This is certainly a preoccupation in my forthcoming novel and, I imagine, many of the stories I’ll tell in the future. What’s that folk tale theme for you?

AK: I’ve always been fascinated by liminal spaces and doppelgängers. My current work-in-progress explicitly concerns both, but I only recently realized that vampire lore also checks these boxes. Early slayers often originate between realms—people who have been near death and pulled back, or have the markings of potential vampires, or who are born at times of the year when the veil between worlds is thin. They are dwellers on strange thresholds. And a vampire, for their part, is a sort of doppelgänger—a revenant that assumes the form of a friend or neighbor, but who is not the person we know.

For me, these can be really interesting stories of identity, which is often deeply intertwined with where we are in the world. I suppose I like stories that destabilize and challenge both our sense of place and our sense of self along with it.

SH: Yes! Bluebeard! I love Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber and often cite the moment the mother rides in on a horse and shoots the killer husband as the first reading experience when I felt truly exhilarated by a female character in a book. (Have tried to replicate this capability and brio in my female characters, even if they don’t have guns!)

I think Anna’s point about thresholds is really important. Where I’m from in the north of England there are lots of “thin places”—areas where the veil between this fundamental world and another can be passed through more easily, another dimension touched or inhabited. In some ways, it’s the geography and topography of the places I write about that attends to folklore first, featuring that wonderful un-boundaried portal element, where anywhere can be possible, uncanny, magical, uncertain. I suppose this is what history is—an overlay, versions of somewhere or someone, changing, referencing, unfinished.

Another aspect that’s always been important to me, and I think can be traced back to old fables, fairytales and myths, is the idea of the human animal (as opposed to the human being), and transmogrification. I’m always exploring our embodied, corporeal, instinctive natures, to the point where a woman might actually become a fox. Or a contemporary version of the Manananggal might be operating with feminist intent in our cities. So, a thinking, opinionated, rude wind is just another amalgamation of human and other.

AEY: I’ve been fixated on many of these uncanny elements since I was a child: portals, transformations, doubles. Likely because they offered me an escape from my reality as an Asian girl growing up in the South.

As an adult, though, I too find myself returning to monsters and monstrosity. I often think of the essay, “Monster Culture (Seven Theses)” by Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, and how monsters are a manifestation of societal fears. How do the creatures of a local folklore reflect that community’s fears? In A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing, the colonizers are monstrous, but so, too, are the outliers of society—those who transgress the conventions of the village or city. In my new work, I am writing about environmental racism in the South and using monstrosity in a new way; here, transformations—birth defects, illnesses from the environment—are not an indictment of monstrosity for the individual, but for larger structures, like corporations and late-stage capitalism in the Anthropocene.

RC: Yes to liminal spaces and doppelgängers, Anna! I’m looking forward to seeing what you’re cooking up. I’m still trying to understand what drew me to George and the dragon, and medieval fantasy in general. I grew up in Oregon and spent most of my childhood hiking and camping, roaming these vast, dark woodlands, and I’m sure that must have imprinted on me and become a guide in my creative impulses. Arthurian legends are always told in these epic settings awash with greenery—actually the placeholder title for my novel was just Greenery while I was working on early drafts.

TT: Thank you for all these vivid and layered thoughts on folklore. In reading them, I’m picking up on the relationship between transgression and liminality and the larger positioning of these stories within a cultural or national identity. As Anna mentioned, we often create spaces through the narratives we tell as a form of resistance and endurance. Can we talk about the role of place in folklore? In my debut novel, Banyan Moon, the swamplands of Florida became that “thin place” (thank you, Sarah, for the language for this space!) through which my characters negotiate their pasts, often encountering the monsters of their memories.

My forthcoming novel has a much greater geographic sprawl, but I see the commonalities: ancient structures brimming with context, the sort of houses that invite ghosts and secret revelations. Characters come first for me when I’m building a story, but place is a close second. With place, I can finally see the shape of a book—its parameters, its mood, its voice. How and when does setting factor into the writing process for you?

RC: Setting plays a huge part in how my book plays out. As you can guess from the title, George falls through time and ends up in 1300s England and I wanted to capture as accurately as possible how that switch from modern to medieval London would feel to someone—not just physically but emotionally. I was obsessed with how “noisey” the silence of pure nature can be and how that would affect someone like George, who’s someone like all of us, constantly distracted by the hum of modernity. Stripping all that away and seeing how George reacts is the bones of the story in my book—and to link that back to the idea of folklore, I only had the basest of storytelling building blocks at my disposal. George is useless, where does he go? Well he needs someone to help him. Then what happens? Folklore deals in these elemental storytelling basics and it felt completely natural to take big dragon-sized narrative risks as I moved George around this world. I wonder how much of a commonality a specifically wild and untamed setting plays in all folk tales.

AEY: Thao, I can’t wait to read this forthcoming novel. Place has come to be central in my conception of my second novel. Not only is this because the book wrestles with themes of the necropastoral and environmental pollution, but also because I wanted to capture the unsettling nature of a “thin place” in the South. I feel like, in contemporary American folklore, the modern fixation is on cryptids, and I’ve been trying to understand how cryptids in the South are a reflection of the environment they are created in. Mostly, I’ve noticed that, though the cryptids may differ, many share similar characteristics and appearances.

On a macroscopic level, I find it so fascinating how the same creatures, storylines, and themes recur in folklore from across the world. How dragons existed in the imagination of both Europe in the Middle Ages and China in the fifth millennium BC, though the cultures were unaware of the other’s existence. And yet, the characteristics of these creatures are reflective of their respective cultures (Chinese dragons are often associated with rain and water). It is a strange doubling that can be found all across history—echoes of the same myths that appear in wildly different places and times.

AK: Before you asked this, I would have said it all starts with character. Now, I realize that I’m still getting to know the people of my second book, but the place (a sort of through-the-looking-glass late-90s Virginia) is already very clear in my mind. Setting also plays a huge part in She Made Herself a Monster—the plot is only able to unfold as it does because of the isolation of the central village. There’s even a folktale interlude about a third of the way through the novel detailing how magic shaped the physical landscape of the story.

TT: Needless to say, I could not be more excited to read your novels. Such span, such intensely thoughtful ways of looking at craft. One last thought and line of inquiry. I’m struck by the way we each make sense of storytelling—the similarities and departures, both—and I wonder if you think about the then-and-now question when it comes to folklore. Our novels share the characteristic of engaging with the past, some as far back as centuries, and to me, that makes sense, given the long-reaching arms of folklore. It almost feels as if we need to go backward to enter the conversation begun by our forebears. When you forecast in the other direction, toward the future, what do you see? What new sorts of folklore are we in the midst of creating? Given that we think of folklore as collaboration, how do you make sense of developments like social media, AI, and even more generally, the evolution of narrative forms? I, frankly, have no helpful answers here, only a blank space I hope you can help fill.

RC: No helpful answers here either, Thao. And I’d hate to be the one to bite the bullet and say memes are our modern day folklore (although maybe I just did!).

AEY: Thank you, Thao, for such thoughtful and interesting questions in our discussion! As to your last question, I am currently on a research deep dive into digital ethnographies: anthropological studies of online spaces like social media or forums. I feel that as more people flock online to find their third spaces, there is an Internet folklore being shaped and molded. (I think of the creepypastas that haunted me in middle school or those chain emails—forward this to 10 people, or you’ll be visited by this terrifying creature in the night.)

Folklore represents the people’s freedom to tell and to make together, as well as to make sense of and solve.

So much of these online spaces, social media in particular, are created for community; inside of them, the primary medium is storytelling, and often the same stories are repeated or mimicked, recreating the oral storytelling tradition of our ancestors. I don’t know which of these contemporary stories will survive and which will be deemed folklore. I do think that folklore is an inherently human creation, and that while modern folklore might be influenced by AI—either as a reflection of our fears towards it or a manifestation of our feelings about its integration into our society: positive, negative, or indifferent—AI can never create its own folklore. It would require too much original thought and humanity, as this discussion has so aptly pointed out.

AK: Alice, I think that’s exactly right. I’m not a fan of “AI art,” but I was kind of intrigued by the earliest AI image generators—the ones that produced images of very low quality, with badly distorted faces, where the seams between their millions of inputs were on display. Those bizarre early outputs felt like glimpses into the collective unconscious of the internet. As soon as they started to look more realistic and people started claiming them as individually-authored art, I lost all interest.

Maybe another working definition of folklore is a narrative with relatively wide acceptance but no clear origin. Urban legends, creepypasta, and conspiracy theories might all then be subsets of modern folklore. (Sustained narrative is a difficult hurdle for memes to clear—maybe they function as dialect?)

The test of endurance recalls nuclear semiotics. How do you warn people thousands of years in the future about the presence of nuclear waste? Some suggest ordaining “atomic priesthoods” to transmit warnings across generations. Others propose breeding cats that glow in the presence of radioactivity, and spreading stories warning against the engineered cryptids. In light of our discussion here, it’s unsurprising that when faced with the challenge of relaying information over thousands of years, folklore and myth emerge as possible answers.

SH: Thank you all for a wonderful discussion. It’s so interesting and tricky to pan forward, thinking of AI and future iterations. (I can’t comment on social media as I’m the last person on earth without it.)

I can’t help but think there is, in part, deep irrationality, joviality, illogic, idiosyncrasy and imperfection to folklore that may always remain a protected province of human creativity, thought and perspective (much as there are common themes, borrowings, and deceptive simplicity to some presentations). I’m trying to think about what folklore and folktales do differently from other narratives, tropes and cultural reflections. It feels in many ways that folklore responds to “dark ages and dark places” by converting them into heightened meaning and experience, warnings, processes, dreams, and if we are in dark ages and dark places now, politically speaking, perhaps environmentally too, how wonderful to feel there will be a wild, unpredictable retort/renaissance/rebellion of folklore as people seek to find color, agency, and fantastical solutions to impossible scenarios.

There’s a big conversation going on in the UK about the need for positivity in climate fiction, for example—paths of light to direct people away from hopelessness and pessimism. Solutions stories. A lot of folklore contains solutions stories and blue sky thinking, doesn’t it? An un-boundness. Visionary freedom. There’s a nice overlap there…I notice now in the UK the prevalence of nature-narrative stories and productions (literature and music particularly) which looks like something of a folk culture revival. For me, folklore represents the people’s freedom to tell and to make together, as well as to make sense of and solve. It is grass-rooted, grounded, jobbing, paradoxically real even when it arrives as naive or magical. It isn’t fake, even if it isn’t accurate. I suppose looking at history, where it has been central to mass discourse, then marginal and “other” to the fine arts (e.g. not prioritized as true art form), that could be interpreted as a very powerful, collective foundation from which to tackle the new dark zones, to disrupt and challenge an establishment future (politicians, machines, money, power). Cats that glow, yes, Anna! I am taking away that image and idea with enormous pleasure!

TT: Me, too, Sarah. Signing off with storytelling, magic, and hope—

*

Thao Thai is the author of Banyan Moon, the July 2023 Read with Jenna title, Barnes & Noble Discover Pick, and Book of the Month selection. Banyan Moon was awarded the Crook’s Corner Book Prize and longlisted for the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize. Thao’s forthcoming novel, The Seekers of Deer Creek, will be released August 4, 2026.

Sarah Hall was born in Cumbria. She is the prizewinning author of six novels, including Helm, and three short story collections. She is a recipient of the American Academy of Arts and Letters E. M. Forster Award, Edge Hill Short Story Prize, among others, and the only person ever to win the BBC National Short Story Award twice.

Ryan Collett is a writer, animator, and knitter. He grew up in Oregon and now lives in London where his first novel, The Disassembly of Doreen Durand, was published in 2021. He also runs a popular YouTube channel dedicated to knitting. George Falls Through Time is his latest novel.

Anna Kovatcheva was born in Bulgaria and now lives in Brooklyn. She holds an MFA in fiction from New York University. She Made Herself a Monster was completed while Anna was in residence at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Her chapbook, The White Swallow, was selected by Aimee Bender as the winner of the Gold Line Press Chapbook Competition; her short fiction has been anthologized in Best American Nonrequired Reading and has appeared in The Kenyon Review and The Iowa Review.

Alice Evelyn Yang is a Chinese American writer from Norfolk, Virginia. Her work has been published in MQR, AAWW’s The Margins, and The Rumpus, among others. She is the recipient of the 2022-23 Jesmyn Ward Prize from MQR and completed her MFA in Fiction in 2022 at Columbia University, where she was awarded the Felipe De Alba Fellowship and nominated for the Henfield Prize. A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing is her first novel.

Thao Thai

Thao is the author of Banyan Moon, the July 2023 Read with Jenna title, Barnes & Noble Discover Pick, and Book of the Month selection. Banyan Moon was also selected by booksellers as an IndieNext pick and longlisted for the Center for Fiction's First Novel Prize. A recipient of the 2024 Ohio Arts Council’s Individual Excellence Award, her work has been published in the Los Angeles Review of Books, WIRED, Elle, Lit Hub, and other publications. She lives in central Ohio with her husband and daughter.