Porn, But Also Literature: On John Cleland’s Fanny Hill

A Conversation Between Chelsea G. Summers and Jessica Stoya

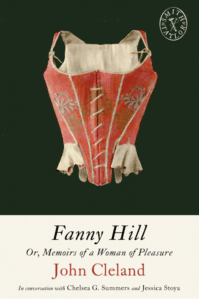

Banned from publication in the United States until 1966 for its assumed obscenity, immorality, and lack of literary merit, Fanny Hill, or Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1749), is a novel considered to be the first original English prose erotica. An important work of political, social, and sexual parody and philosophy, this is the tale of the titular Fanny Hill, told to us in her own letters with “stark naked truth,” in which she recounts her early days of prostitution in bawdy 18th-century London and her dramatic rise to respectability. This uncensored version coming January 6, 2026, from Smith & Taylor Classics is set from the 1749 edition and includes a new introduction by Chelsea G. Summers. Here, Summers and Jessica Stoya discuss everything from the language of war used in Cleland’s erotic literature to how sex in storytelling has developed over the years since.

*

Chelsea G. Summers: I’m curious, knowing what I know about you, it doesn’t seem like you’ve had a lot of experience with eighteenth-century literature. How was it coming to this novel and reading the language? How did it stack up against your expectations versus your actual experience?

Jessica Stoya: I had a bit of familiarity with American eighteenth-century political writing, and the Marquis de Sade in France wasn’t too far behind John Cleland, but my understanding of English literature in the mid-1700s is very, very slim. When Fanny Hill started to get wacky and wild, both in choice of language and scenarios, I kept telling myself, Chelsea Summers asked me to read this. Chelsea Summers wants to discuss it, so I have to keep going.

CGS: I did ask you to read this and discuss it with me. When I got this opportunity, you were the first person I thought of to talk to. I’m wondering, how do you put Fanny Hill within the framework of your background as an adult film and stage performer, porn director, and writer of sex, both fiction and nonfiction?

JS: From my experience as a woman who’s worked very publicly with sexuality, it’s wildly entertaining to me how completely relatable the story itself is and how the plot takes one of the two pathways available to female sex workers in fiction since the beginning of the industrial era. Either they end in tragedy and complete ruin (i.e., trapped forever or death), or they can move on, having accrued enough literal wealth and a respectable heterosexual marriage, however critique-able that may be.

The entry into sex work is often nice women who show up and offer you a position under somewhat murky circumstances.

CGS: It’s amazing how much the book conforms to this concept of middle-class bourgeois respectability, even as it works in tremendous tension against it. The eighteenth century had this enormous project—particularly with young women but also some men—about building the respectable middle class. The middle class as an idea, the middle class as a set of traits, and the middle class as industrious, clean, neat, everything in order. You live a very tidy existence around your family and around accruing things to give to your family after you die. This book both plays into that narrative and pulls against it. I think the first half in particular pulls against it.

JS: Absolutely. In the first half, I was struck by how much the loss of Fanny’s parents resonated with what I saw in forums and blogs when I went into performing in the mid-2000s. They were dedicated to true fans of pornography (like the people who care enough to know the names of performers or directors or production studios), and it was common to see this really superficial but strong need to understand what made a woman turn to this work. This curiosity seems to function as a way of justifying their consumption of it, right? This person somehow stepped outside of respectability, off of the path of normal life. It couldn’t be for anything else but trauma. Obviously, none of these ideas are accurate when applied to the realities of actual humans. So from the first page, I’m like, Ah, yes. Of course Fanny has lost both of her parents, and this is how she begins to embark on this journey.

CGS: I think that there is a will on the part of people who have never done sex work to assume that everybody who is doing it has suffered some kind of trauma, but what is also interesting is that in the eighteenth century, it was not uncommon to be fifteen and have both of your parents die from a sudden fever. There are so many novels in the eighteenth century where one or both parents are dead, so while it fits into this contemporary trope of like, Oh, what broke her? it also fits into a very old trope of like, Yeah, your parents died and you don’t have any money. What is our plucky heroine going to do? Of course you end up adrift in London, and Mrs. Cole comes by and is like, My poor dear, come and be my companion.

JS: You know, the entry into sex work is often nice women who show up and offer you a position under somewhat murky circumstances.

CGS: Speaking of nice women, Fanny is coerced/groomed/seduced into sex work by another woman, which also fits into a trope that we see in Jane Austen’s Emma, in Fanny Burney’s Evelina, in contemporary movies like The Handmaiden, which is also a novel, where you have young women grow into comfort with heterosexuality through their friendships with women first. Emma only realizes that she’s attracted to Mr. Knightley through the mentoring and unsuccessful matchmaking of her friend Harriet. In many ways, Harriet inadvertently leads Emma into her own heterosexual awakening. And what makes The Handmaiden so interesting is how it subverts the expectation that Sook-Hee’s friendship with Lady Hideko will lead Hideko to marriage. There’s this strange, implied understanding that friendships with women are just a bridge to the proper straight relationship with a dude.

By virtue of being the first publicly circulated work of this kind in English, I imagine that it’s been really widely read by people who created later pornographic material.

JS: So then we get into the first of the firsts, which the modern porn industry runs on. First kiss, first time, first love. Each first in porn is broken down into small details, like the first sex scene should be solo so you have all the other firsts left. Then your first scene with another woman, and then your first scene with a man. We see that in Fanny Hill, and it speaks to this enduring fixation the (largely male) paying consumers of any kind of pornographic material have with novelty. There are so few opportunities for true novelty in the world that we humans push the envelope everywhere, from sex to reusable water bottles, by being like, Okay, it’s the same thing you’ve seen five hundred times, but we’re changing one small detail so it feels slightly new, just different enough to get you excited.

CGS: Yeah, one of the things that we see in this novel is Fanny’s almost infinite loss of her virginity, right? Whether it’s Phoebe’s hand trying to sneak past her hymen, or the old, lecherous guy whom she runs away from, or the first time she sees people having sex and gets excited by it and orgasms. Or the time when she fakes having lost her virginity with a little sponge in the bedpost. I find that extremely clever, because who doesn’t need bedposts with secret spring-loaded doors that pop out bloody sponges? There’s also the language that repeats over and over again: the phrase “like a virgin” plays throughout the course of the book.

JS: I think that the persistence of the concept of “like a virgin” is often referring more to an energy of being present and engaged and responsive.

CGS: And also in this book, pain. It’s a lot about causing and experiencing and witnessing discomfort that changes into pleasure, and it doesn’t happen once. It happens basically every single new time somebody has sex in one way or another.

JS: The physical loss of virginity, whether men can admit this to themselves or not, is half punishment, coming from a culture so informed by Christianity where women gotta suffer, and half This is unconquered territory. It seems an extension of this book being published in an England so heavily supported by territories “claimed and saved” by the empire. Sex is not always painful, and often when it is, it’s like, That is an uncomfortable pinch and now we’re done with that. Yet Cleland describes that pain or discomfort as constant and horrific.

CGS: Yeah, there’s a fixation on size and on pain. Size matters for John Cleland.

I do want to touch on how despite this being the first published erotic novel in English, there was this whole currency of erotic writing that was mostly shared among friends and libertine clubs. The eighteenth century was absolutely filthy with clubs, and there’s some pretty good evidence that Cleland was part of one that predated the Hellfire Club briefly before he went off to Bombay. He may have joined up again later on his return to England, when it was just a bunch of men who believed themselves rational pleasurists and wanted to enjoy sex with willing women and also men. Erotic snuffboxes were really big. How you tied the garters on your legs that held your stockings up with your breeches was another sign of whether or not you were a libertine. There was an entire society of generally well-born guys, most of whom were born into money and were well educated, and that was their thing. It really was a secret society.

So the idea of this manuscript being the first, right? In reality, it was one of many. It was just the first that ended up in print, and mostly because Cleland didn’t use a single dirty word, so you can’t fault it for its language. You can only fault it for what you think about when you’re reading it. I do think virginity to this group of men was a very potent symbol, as well as a shared experience and a way of communicating, like, She was in pain, but I, the rational pleasurist, was able to turn that pain around with my wonderful machine and my lady’s bag of candies and turn it into balsamic joy.

JS: I will never get over the phrase “balsamic injection.”

CGS: I mean, I think you can imagine what I said to my husband in bed the other night.

Interestingly, though, when Fanny finally does lose her virginity, she does it outside of commerce. She loses her virginity to Charles, the love of her life. It is an almost idyllic, noncommercial meeting of two “mossy” lily-white natural beings who are clearly made for each other. Then he gets called away to the South Seas by his cruel father, and she’s pregnant and miscarries. She has to go back to Mrs. Cole’s because she’s broke, and the language is very bereft, where Fanny says things like, I felt nothing. I felt empty. I experienced no joy, which undercuts what are typical erotica tropes. You’re not generally reading along, thinking, Ooh, sexy, sexy, we have a miscarriage, right?

JS: By virtue of being the first publicly circulated work of this kind in English, I imagine that it’s been really widely read by people who created later pornographic material. But as depictions of sex being published for the general public began to increase, the government opposition and censorship of them is also going to increase and become more elaborate. It totally makes sense, given the timeline, that Cleland would have full discussion of a miscarriage in his reason for why Fanny does not stay with Charles forever, and then, as time goes on, the body of pornographic work coming after would say, Yeah, that was a choice, sir, but we’re not going that far.

CGS: One of the things that’s interesting about it is, yes, there were very questionable condoms, and there were very questionable practices that theoretically worked as contraceptives but didn’t. So if you were a sex worker, you got pregnant and you got sexually transmitted infections, but we get this one pregnancy. The reason why I think it sticks out is that it’s with the love of her life, right? He is the person that she most genuinely enjoys sex with. In the pantheon of all the people that Fanny has sex with, the sex with feeling is at the top. Below that, sex with somebody who is technically able and attractive, then sex because you’re curious just below. Sex that you are really not into but end up doing for one reason or another is clearly at the bottom.

And so I think that moment, in part, is Cleland driving home how special Charles is. In 1740 there was still this belief that you only got pregnant if you orgasmed, so if you claimed rape and got pregnant, the case would get thrown out. Because she gets pregnant by Charles, the implication is that he is the person that she most enjoys having sex with, and it’s probably like the bourgeois ghost raising its little hand and being like, Excuse me, we gotta restore heterosexual order for a moment. Then she has this catatonic breakdown and ends up taking up with Mr. H——.

JS: She’s so numb and so passive after the loss of Charles and after the loss of her pregnancy, but in contrast to when she first ends up in Mrs. Cole’s hands and really doesn’t know what she’s signing up for, the vibe on Fanny’s part is Well, I guess this is fine, until Mr. H—— has sex with her lady’s maid, which to Mr. H—— isn’t anything that could possibly be critique-able, but the way that Fanny reacts, it’s as though she has been spurned and cheated on. There’s this anger, which is what gets her to start making actual choices again. Are they chaotic choices? Absolutely. Do they get her thrown out of Mr. H——’s care and thus move the plot along to more and more novel sexual combinations? A hundred percent.

CGS: Absolutely. Cue Fanny’s rendezvous with Will, a country boy who comes to town to be Mr. H——’s personal assistant. Before Will knows it, Fanny is unbuttoning his trousers and letting loose his “engine of love.”

JS: God, “engine of love.” Another phrase I will never get over. But to seduce Mr. H——’s servant and then have sex with him where there is a risk of being caught is like a return to self-determination for Fanny. It’s all we can ask, at this point, of a sixteen-year-old girl.

CGS: What I find particularly funny about the end of the first part is that Mr. H—— is like, Yeah, dang it, you’re right. I shouldn’t have done that. That was wrong, so here’s a pile of money, not as much as I would have given you, but, you know, it’s a pile of money. [Note: I later did the math and discovered that Mr. H—— gives Fanny the modern equivalent of about $14,000 today.]

Of course, Mrs. Cole is now out of business, and because she is bored, Fanny gets introduced to a whole cadre of women, including one who runs the bawdy house that she ends up going to. We get this cavalcade of anecdotes, of different scenes, in the second half of this book, and they’re all very discrete and woven together in the most slender tissue of narrative fabric.

There is this strange writerly fixation on the very limits of trying to tell these kinds of stories and trying to do this narrative work without getting dirty.

JS: The first half is virtually a straight line into what, at the time, for a middle-class girl would have been conceived of as a loss of virtue, and in the second half, although the sexual acts described escalate, Fanny’s reactions begin to get complicated. The interaction she observes between the two men and her reaction of revulsion of their homosexuality, that’s the first time that she really judges, right? There’s shame in the introductions to the letters throughout, but she is passing moral judgment on sex now. It sticks out, and pretty quickly too after she has what we would now describe as her bag of cash—resources inherited from the man that she took care of in his old age.

The sex scenes in the second half are strikingly similar to how after the piracy-driven tube sites took over the adult video industry, creators began to do this sort of grab bag mishmash. Like, We’re going to take three popular tags and just mash them together to make something, as opposed to when earlier tube sites would attempt storylines to justify why the sex was happening, much like the first part of Fanny Hill.

CGS: The second part does feel like a money grab. Probably because the first part Cleland rewrote from an old manuscript, and the second half he wrote to seal the deal to get out of debtors’ prison. There is a weird tonal shift where the first half feels more like a novel of sensibility—by which I mean “feeling”—and the second half really feels like what we think of when we think of porn—by which I mean an episodic, almost chaotic cavalcade of sexual activity. What is really interesting to me in the two halves is how Cleland begins the whole second half with a massive writer’s lament. He’s just like, I am so sorry about having to repeat, you know, “engine of love” and “machinery” and “moss”-covered “clefts” and “oily balsamic” . . . I only have so many words. So there is this strange writerly fixation on the very limits of trying to tell these kinds of stories and trying to do this narrative work without getting dirty.

JS: I’m reminded of Florence King’s When Sisterhood Was in Flower, where Isabel, the writer, starts writing porn novels but starts to burn out. She sits and she tries to describe the boiling and eating of an egg, and eventually she gets to the line “the pulsating, quickening core gushed out into my egg cup,” and she’s like, My god, I’m broken. In Cleland’s attempt to avoid the direct words, he’s created these massive, slippery, goopy, fleshy paragraphs upon paragraphs that are so much more visceral and evocative and affecting than if he had said, you know, There was this assistant, and he took out his big cock, right?

CGS: There is a slipperiness of bodies because he’s so mired in metaphor throughout the entirety of the book. There is this fixation on the enormity of everybody. It seems to be telescoping phalluses, like one is ever larger than the next, but beyond that it almost feels like a phantasmagoric mishmash of flesh, and with that comes this switching of perspectives. Here’s Fanny, a female narrator telling us the story, and sometimes we get views that, as a woman, you just cannot see. I mean, maybe if you’re incredibly acrobatic, but we don’t get a sense of Fanny being particularly flexible, because I’m pretty sure she’d mention it. You get this very masculine view of bodies interlocking, and at the same time, there’s this language that feels antagonistic. It’s always this mounting of an attack. There’s this language of war and violence that feels extremely masculine coming from our titular heroine. It’s cognitive whiplash, like we’re in a gender blender.

JS: I found myself often wondering, Okay, whose youthfully plush mouth is on whose well-shaped you-know-what? which does this really interesting job of articulating how unmooring and overwhelming being engaged in good sex can be. You don’t know which end is up, or if there is more than one partner, you may legitimately not be sure who is doing what at what time or whose parts you’re touching.

CGS: At the same time, the discussions, especially in the second half where we have Fanny and her three bawdy sisters with the four courtiers, feel almost like a court dance. It’s like, I do this to you, two, three, you do this to me, three, four. You can almost hear the harpsichord in the background. There is this Enlightenment aesthetic and this gender blender happening at the same time, and I find it very disorienting on a linguistic and syntactical level, as well as on a visceral level. Those two scenes that rip us out of that, which are the ones that you mentioned before: when she stands on the chair and spies on the two guys having sex, and has this extreme, almost methinks the lady doth protest too much moment, and then falls off the chair and faints, which is legit funny; and then the scene that comes right after that, which is when Louisa coerces/seduces the mentally challenged, overly endowed flower seller. Both of those scenes are very discomfiting to read. I want to speed through them because I find Fanny Hill’s homophobia discomfiting, and the second one I find discomfiting because the lack of consent is upsetting. Those two scenes ripped me out of that episodic, anecdotal narrative.

JS: When it comes to the flower seller, no argument on the stance of coercion and lack of consent in that scene. With Fanny’s whole story, there’s a really decent amount of coercion and murky consent, and I think that speaks partially to how we are so used to women being coerced and sexually taken advantage of.

However, with the amount of cultural discussion around consent and destigmatizing sex work nowadays, we know how we feel and how we want to feel. We have some idea of what we think should change in the world to reduce harm. But when it comes to something like the scene with the flower seller, nobody knows what to do with intellectual differences and sexuality. There’s discomfort, like, Oh god, I don’t even know how to think about this. I just know I feel bad reading it. It’s harder to grasp because we haven’t had the necessary cultural discussions around consent and disability of any sort, despite best efforts from groups such as Sins Invalid.

CGS: We also don’t have a history of it. I mean, when Cleland wrote the scene where she’s watching the two men, sodomy was against the law. One of Cleland’s best frenemies called in Cleland’s debt, which is what landed him in debtors’ prison and led to him publishing Fanny Hill. This man was openly gay and wrote a defense of sodomy. I think that scene was very much colored by not just the cultural animosity toward gay people and generalized homophobia, but also Cleland’s own spite. [I should also note that biographers have discovered some fairly compelling evidence that Cleland had male lovers in his lifetime, so this moment may have also grown out of his ambivalence about his own sexuality.]

But the second scene with the mentally challenged flower seller, I’ve read a lot of narratives of sex workers from the eighteenth century, and I have never seen anything like that before and never seen anything like that since. I cannot wrap my head around it. I just find it profoundly upsetting. It almost feels like the narrative does too, because right after that, voilà, there’s Charles, ready to wife her up, and she has her money.

There’s a level in which Cleland is saying that all of this deviance, all of these sexual desires and oily balsamic injections, are part of bourgeois life.

JS: I find that ending interesting because it aligns with the consistent cultural message that we see, which emphasizes the idea: But in the end, they made a lot of money, right? From the E! Entertainment television special on Jenna Jameson several decades ago through to the coverage of Bonnie Blue today, the monetary gain is the justification for all of this behavior. When prominent porn stars such as Jenna Jameson and Tera Patrick have done their memoirs with large publishers that get widely circulated, they go in bookstores where people who don’t have a particular interest in sex industries might find them. It ends with an emphasis on: Look at my material wealth and my husband, see the husband, I have the husband in the end. In the end, there is conformity with bourgeois values without discussion of the costs to individuals and the entire concept of human equality.

CGS: Yeah, like if at the end you have a “normal” middle-class life, then sex work is work, right? My take on it is that at no point throughout the book, even for all the scandalous things that happen and all of the vagaries of Fanny’s fortunes, at no point does it really diverge from bourgeois values. Everything is orderly. Everything is in its place. I mean, things get a little messy, because of course houses get messy, but everybody’s demure. All of the women working in the bawdy houses are modest and never look lascivious because, Lord knows, that would be horrific. In one way, it is the natural ending. In the other way, I look at what she said in the framing of the novel: I’m telling you this so you don’t do it, but also look at my rise in fortune, education, and my rise in station.

In the end, we have this tailpiece of morality—and it is explicitly called a “tailpiece,” with all that is inferred. While the word “fanny” at this point in time did not yet carry the British meaning of the entirety of a woman’s vulva, nor did it mean “butt,” “tailpiece” is pretty clearly “tail.” She’s talking tail. There’s almost this wink at the end where Fanny says, By the way, Charles brought our son to bawdy houses so he could be educated just as Charles was. There’s a level in which Cleland is saying that all of this deviance, all of these sexual desires and oily balsamic injections, are part of bourgeois life.

JS: The subversion of middle-class expectations is really blatantly just under the surface in the end as well, because Charles has no money. The script of patriarchy is the man provides, right? So there’s this massive reversal of how the economics of the heterosexual marriage are supposed to be in the middle of this fairy tale.

CGS: Absolutely. So you used to run a book club called Sex Lit, and at the end of each book, you’d ask a couple specific questions, which I know because I was part of your book club. So I have to ask: Is this book literature? Is this porn?

JS: Hardly ever is a book both, but in this case, I think, yes. The literature part fumbles around a lot, which is, as you’ve mentioned separately, pretty standard for eighteenth-century literature, since they were still figuring out what a novel could do. But that it, over and over again, steps away from the story to have these visceral digressions that exist to push the emotional response buttons of the consumer and returns to the story so it can move on a little bit and do it again? Definitely porn.

CGS: Porn, but also literature. Sometimes a girl can have it all, with a little balsamic on the side.

__________________________________

From Fanny Hill: Or, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure by John Cleland. Copyright © 2026. Available from Unnamed Press.

Chelsea G. Summers and Jessica Stoya

Chelsea G. Summers is a former academic and college professor with Ph.D. training in eighteenth-century British literature. A freelance writer, Chelsea's work has appeared in New York Magazine, Vogue, The New Republic, Racked, The Guardian, and other fine publications. She splits her time between New York and Stockholm, Sweden. A Certain Hunger was her first novel. Jessica Stoya has been a pornographer since 2006 and a writer since 2012. She has written for the New York Times, the Guardian, Playboy, and others. She has acted in Serbian sci-fi feature Ederlezi Rising and two of Dean Haspiel’s plays in Brooklyn and Manhattan. She lives in Los Angeles.