Pop Culture in a Post-Truth America

On the Political Implications of TV's New Self-Consciousness

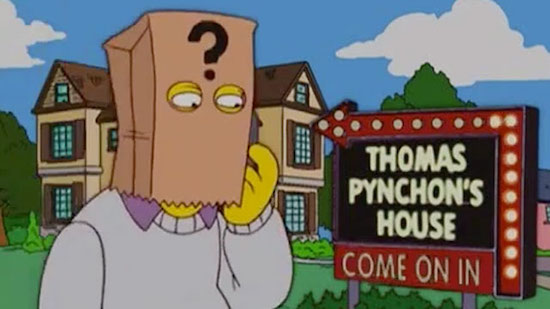

Thomas Pynchon is a master of American metafiction and one of our last literary recluses. He rarely makes public appearances, but when he does, they tend to be on The Simpsons. Pynchon has appeared twice on the show so far, delivering jokes about his novels through a bag on his head, anonymous even in animation. It makes sense: The only thing more meta than an average episode of The Simpsons is a Pynchon novel like The Crying of Lot 49. And the only thing more meta than The Crying of Lot 49 is Pynchon joking about The Crying of Lot 49 on an episode of The Simpsons.

If this kind of meta head-trip was one of The Simpsons signature tics, it has become, at this stage, a typical development of TV in 2016. A slew of recent shows have begun to obsess over their own artifice and the slipperiness of storytelling, often scaling the fourth wall entirely. Frank Underwood delivers his Machiavellian monologues directly to the audience on Netflix’s political drama House of Cards (borrowed from the original BBC version, which debuted a year after The Simpsons); Showtime’s pulpy, po-mo romance The Affair is structured around the Roshomon effect: the narrative woven in one character’s recollection is unraveled in another’s; on USA’s Mr. Robot, hacktivist Elliot addresses his monotone voiceover to his audience of “invisible friends”; and the unnamed narrator on Fleabag treats the camera as her confidante, all slapstick dynamism to Elliot’s monotone dread. TV—once the medium of broad, straightforward storytelling—has become meta to the point of mania.

In an era where politics seem to have abandoned truth, TV has abandoned verisimilitude for the cannily post-modern: defined by endless, obsessive self-scrutiny and a pervasive atmosphere of distrust. Maybe TV has caught up with post-war fiction; maybe it’s merely caught up with the demands of the present. At any rate, while everyone talks about TV, TV has apparently learned to talk about itself. It’s still unclear, though, if it has anything interesting to say.

* * * *

Previously, it was TV’s unhippest formats that had the most success with risky exercises in self-awareness. Flavorwire’s list of “the 50 Most Meta TV Shows of All Time” predominantly features sitcoms, and it’s easy to understand why. The form’s characteristic features lend themselves especially well to meta self-mockery. Few things are more meta than the pre-recorded laugh-track, which reminds audiences at home of the “live studio audience” near the soundstage. And while millennial sitcoms nixed the canned laughter (taking a cue from the groundbreaking Gary Shandling Show), the favored mockumentary format of The Office and Parks and Recreation stretched a meta gag into a whole genre: half the fun of The Office was Jim Halpert’s baleful glances at the camera. Unlike other formats, the sitcom was always willing to make fun of its own fakery, inviting audiences both into the joke and onto the set.

But, until recently, TV’s so-called golden-age—largely constituted by antihero-driven cable dramas—steered away from the cheeky self-exposure of the TV sitcom. If the sitcom’s signature gag was to remind you, with every punch-line, that you’re watching a sitcom, the prestige drama has always tried to convince you that you’re watching something more like a novel. Frequently lauded in literary terms, shows like The Sopranos, Mad Men and The Wire were more often compared to realist fiction or Greek tragedy than to their immediate TV predecessors. Those dramas weren’t interested in puncturing the illusion of storytelling—they were interested in perfecting it. The breathless intensity of shows like Breaking Bad turned its audience into stressed-out wrecks, not paranoid skeptics. Shows like Mad Men and The Sopranos were so studiously paced that that they risked banality rather than disbelief. Whether “gritty” or lush and literary, their style was always realism.

But, strangely, the emergence of the prestige drama coincided with a time when all of televised reality began merging with fiction. The Sopranos premiered a few years after The Real World and Big Brother debuted a new, flamboyant type of unreality onto the screen. Court TV had been on air for the better part of a decade and premiered the same year as the ur-reality exploitation show Jerry Springer. By the late 90s, the TV screen had become irreversibly weirder than any page in a novel: a porous membrane between fact and fiction, entertainment and information, truth and falsehood. Nowadays, the phoniness of televised narratives is so widely acknowledged that we can watch a dating-based reality show (The Bachelor) and a dramatic series about the fakery of dating-based reality shows (UnReal) on the same screen. On TV, the end of truth was a new beginning for entertainment.

It was also the beginning of a new political era. “Post-truth” has become the favored adjective for describing public life under Donald Trump and, as of November, Oxford Dictionary’s “Word of the Year.” It’s a good handle for a political moment which feels at once pre-Enlightenment and post-modern, estranged from reason and dominated by media spectacle. Trump’s propensity for conspiracy theories, wild inaccuracies, and outright lies is well documented; indexing them has become both a Sisyphean task and a matter of routine. None of it, though, has stopped him from becoming our president-elect. And while Trump might be the first US president elected on a post-truth platform, the so-called “post-truth era” precedes him. The term was first coined in The Nation in 1998, and explored at length in a book, The Post-Truth Era, in 2004 by Ralph Keyes. Although written in the early years of the millennium, Keyes’ insights feel spookily prescient: he describes his moment as one in which “deception has become a challenge, a game, and ultimately a habit,” blurring the borders “between fiction and nonfiction.” And, while our crisis of knowledge is typically blamed at least in part on social media, Keyes asserts that “the emergence of post-truthfulness is linked inextricably with the rise of television.” Post-war audiences grew up “against a backdrop of televised McCarthy hearings, rigged quiz shows, [. . .] Vietnam and its many credibility gaps” and “the Watergate hearing,” among other things. Quoting Landon Jones, Keyes writes that “TV gave its audiences their ‘first lesson in the little dishonesties of adult life.’” But the dishonesties he rattles off don’t seem so little—they weren’t then, and they aren’t now.

* * * *

From boomers to millenials, TV is where many of us first learned to be media skeptics—and the skepticism that TV once provoked has now become one of its most popular premises. Unreliable narrators proliferate on television as unreliable narratives proliferate throughout our post-truth culture. We’ve become so accustomed to distrusting both official and unofficial narratives, on TV and elsewhere, that the very language of storytelling has become cluttered with new meanings. Even the word “narrative” feels, at least when used by the powerful, roughly synonymous with “propaganda.” We all understand that “controlling the narrative” is something that Taylor Swift, Olivia Pope, and the president all have to do to get by—and that it has a lot to do with lying. So, too, has the word “story” undergone an untoward transformation of meaning. As Vinson Cunningham wrote last year in The New Yorker, “a story has lately become a glossier, less thrilling thing: a burst of pathos, a revelation without a veil to pull away. Storytelling, in this parlance, is best employed in the service of illuminating business principles, or selling tickets to non-profit galas, or winning contests.”

Storytelling has become hard to consider without cynicism, so it’s no surprise that TV, at this juncture, has become coy and self-conscious. When Westworld presents itself, as Emily Nussbaum suggests, as “an exploitation series about exploitation,” or when Paul Spector on The Fall screams “Why are you watching this?” into the camera, it’s clear that TV has become its own critic as well as its own historian. Last year’s excellent The People Vs. OJ Simpson is, essentially, an origin story for the 24-hour news cycle and all its distortions. On CBS’s Scandal, Olivia Pope is a presidential mistress, a rigger of elections, and an unreliable narrator for hire: a PR “fixer” who spins the narratives of celebrity scandal for a living.

The question remains, though, of whether TV can turn self-consciousness into self-knowledge. So far, the meta hijinks on House of Cards, Mr. Robot and The Fall have fallen considerably short of self-critique. Mr. Robot’s unreliable narration is less a meaningful commentary on the naïveté of TV audiences than a justification for increasingly implausible plot twists. House of Cards breaks its fourth wall not to unsettle viewers, but to mainline Kevin Spacey’s menacing charisma directly to the them. And this is to say nothing of the meta maze of Westworld, which amounted, as Matt Zoller Seitz describes, “to an elaborate series of perception games played by the creators.” It’s hard to tell, then, whether the recent explosion of meta TV is a meaningful response to what we now call the post-truth era, or merely its logical result.

At any rate, it feels appropriate. Fiction is consuming itself at a time when public life is consumed by fiction at both ends: While the Right pursues conspiracy theories until it’s shooting holes in pizza shops, liberal culture has cocooned itself in fantasies of Parks and Rec and Harry Potter. The latter is innocuous, maybe. But it’s frustrating in a time when fiction seems to be steadily overtaking truth. Few things have felt more futile, in retrospect, than the way political campaigns have pandered to youth culture, aligning themselves with pop fiction on TV and elsewhere. And that futility seems to live on as farce in the pop-culture crazed response following the election: the tone-deaf speculation about which Star Wars episode this chapter in our political history most closely resembles, or whether The Hunger Games predicted the rise of a fascistic demagogue. As Jacob Silverman writes at The Baffler, pop-culture fiction “excites cultural anxieties only to soothe them, leaving consumers spent and satisfied.” Far from reckoning with political reality, liberal culture would seem to be retreating ever further into its own escapist fantasy.

But the truth is that there isn’t that much escapism left on TV—or, for that matter, fantasy (Game of Thrones notwithstanding). From standard Bravo fare to brainy dramas like Mr. Robot, TV has been encroaching ever further on the real world. It makes sense at a time when politics are sold to us as entertainment, and a former reality show star has now become president. TV may not be a perfect analogue for our political moment, but it might also be the best one we have: most of us didn’t predict Trump’s presidency, but The Simpsons did.

Emily Harnett

Emily Harnett is Philadelphia-based writer on contemporary fiction and pop culture. Her other writing can be found at Broadly and Jacket2.