“Polluters Will Be Looked Upon as Swine.” On Kurt Vonnegut’s Environmental Activism

Christina Jarvis on the Literary Icon’s Advocacy for Planetary Citizenship

When Kurt Vonnegut took the stage in New York City’s Bryant Park for the 1970 Earth Day rally, the crowd was jubilant. It was an auspicious day for the beginning of the environmental movement. The sun beamed down on the marchers on Fifth Avenue, peaceful demonstrators sang and carried daffodils, and a brass ensemble played fanfares on the steps of the New York Public Library near the speaker platform. Noting the joyous mood, Vonnegut opened his speech with a joke: “It is unusual for a total pessimist to be speaking at a spring celebration. Anyway, here we all are.”

He wasted no time getting to his central point: that the Earth Day demonstrators needed to get President Nixon’s attention, because “he has our money and he has our power.” Responding to Nixon’s decision to sit out the events, Vonnegut wondered “which sporting event the president was watching. .\.\. Perhaps a boxing match by satellite” television.

This jab at Nixon was personal for Vonnegut, who had participated in the Washington, DC, Vietnam Moratorium march the previous November while Nixon watched college football, deliberately ignoring the crowd. Critiquing the administration’s decision to prioritize military spending over environmental protection, Vonnegut soberly declared that Nixon’s worries over being the “first American president to lose” a war were misplaced.

“He may be the first American president to lose an entire planet,” Vonnegut declared. Like the thousands of other Earth Day speakers, who called for science-based, ecological perspectives, Vonnegut leveled his most urgent critique of Nixon at his profession: “I am sorry he’s a lawyer; I wish to God that he was a biologist.”

From the grand scale of national policy change and planetary survival, Vonnegut shifted to the small actions that nearby marchers were making while the Vietnam War continued—“picking up trash missed by the Sanitation Department.” These efforts, Vonnegut feared, would be no match for the pollution masked by “great advertising campaigns,” the Nixon Administration’s inattention, and an economic model where “polluters are looked upon as ordinary Joes just doing their job.” Vonnegut predicted, “In the future [polluters] will be looked upon as swine,” and he had final, comforting words for his audience: “Those who try their best to save the planet will find a loose, cheerful, sexy brass band waiting to honor them right outside the Pearly Gates. What will the band be playing? ‘When the Saints Come Marching In.’”

The main way Vonnegut responded to the urgent environmental issues he addressed on Earth Day was through writing.

When the Village Voice published coverage of its April 21 interview with Vonnegut and his Bryant Park speech, Anna Mayo reported that of all the speakers, “he was the gloomiest.” While responding to his opening comment and pessimistic take on the Nixon administration, Mayo also highlighted Vonnegut’s claim that the environmental movement was “a big soppy pillow.” Vonnegut bestowed the label because he predicted, “Nobody’s going to do anything.” Vonnegut, of course, was famously wrong. Earth Day helped create the first “green generation” in US history, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), bans on DDT and leaded gasoline, the Clean Water Act (1972), the Endangered Species Act (1973), and other landmark legislation.

Perhaps it was because of Vonnegut’s failure of vision that the Village Voice retitled Mayo’s piece “Kurt Vonnegut Tries to Spoil Earth Day” when it republished it forty years later. Or perhaps the retitling was inspired by Vonnegut’s dire late-life predictions about climate change or early posthumous portraits of the author as a “congenitally gloomy” chain-smoking prophet of the apocalypse. What all these characterizations miss is that beneath Vonnegut’s surface pessimism lay deeply held beliefs in planetary citizenship and engagement. They also miss the fact that much of Vonnegut’s writings was richly conversant with, and sometimes ahead of, environmental approaches throughout his career.

Read in the context of the more than fifty speeches collected by Environmental Action, the group coordinating Earth Day, Vonnegut’s speech seems neither out of place nor particularly gloomy. Nixon got off light in Vonnegut’s remarks compared to the scathing critiques leveled at the president by politicians Adlai Stevenson, Gaylord Nelson, Richard Ottinger, and Frank Moss. Vonnegut’s criticisms of anti-litter campaigns and corporate greenwashing, meanwhile, were in line with those of key Earth Day organizers, including national coordinator Denis Hayes. Environmental Action flatly refused all corporate funding, and Hayes condemned the politicians and business leaders who tried to “turn the environmental movement into a massive anti-litter campaign.”

Vonnegut also immediately contradicted his claim that no one was going to do anything about environmental change. He donated his speech to Environmental Action, which used the royalties from sales of Earth Day—The Beginning to fund an explicitly political agenda aimed at unseating congressional leaders with the worst environmental records as well as implementing widespread legislative, social, and cultural change. He also gave the Wave Hill Center for Environmental Studies permission to use his May 1970 Bennington address in its new “Earth Kit,” a free collection of “the finest available” environmental readings, for use in New York City schools.

The main way Vonnegut responded to the urgent environmental issues he addressed on Earth Day was through writing. In the months following his Bryant Park speech, he revised his off-Broadway play Happy Birthday, Wanda June to include more didactic environmental messages, strengthened his critiques of America’s polluting car culture in working drafts of Breakfast of Champions, and irreverently went after hypermasculine technological fixes to Great Lakes pollution, invasive species, and human population issues in his final short story, “The Big Space Fuck.”

In fact, he was so deeply affected by Isaac Asimov’s predictions about global warming and his own responsibilities to the nation’s youth that he abruptly cut short his speech at the Library of Congress on February 1, 1971, and cancelled all speaking engagements for six months. Vonnegut, who could joke about virtually everything, wept later that evening and, according to his longtime friend and agent Don Farber, was troubled by the event for the rest of his life.

Both as a writer and as a New York City resident, Vonnegut frequently returned to the site of his Earth Day speech. In Slapstick, Wilbur Daffodil-11 Swain explains his campaign to end American loneliness via artificial extended families on those same steps. In Jailbird, Walter Starbuck spends hours admiring springtime flowers in Bryant Park on April 22. And in Timequake, police officers pick up Kilgore Trout at the New York Public Library and transport him uptown, where his creed would do “as much to save life on Earth as Einstein’s E equals mc squared had done to end it two generations earlier.”

By the time Vonnegut completed his final novel, he was still worrying about the possibility of a “dying” planet, but he had come up with kinder words to describe the Fifth-Avenue-littercollecting saints. As he explained in Timequake, he defined a saint “as a person who behaves decently in an indecent society.” Fittingly, thirty-seven years to the day after he described the burgeoning environmental movement as a “big soppy pillow” in his interview at the Algonquin Hotel, Kurt Vonnegut’s memorial service was held there, with a brass jazz trio led by trumpeter Tatum Greenblatt. The trio played “Back Home in Indiana” and New Orleans–style renditions of “Amazing Grace” and “Fly Away.” If only they had played “When the Saints Come Marching In.”

__________________________________

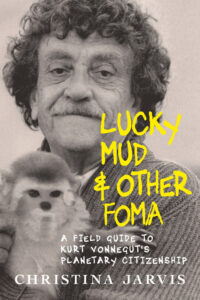

Excerpted from Lucky Mud and Other Foma: A Field Guide to Kurt Vonnegut’s Environmentalism and Planetary Citizenship by Christina Jarvis, available via Seven Stories Press. Top image: Photo by Mike Slaughter/Toronto Star via Getty Images, provided by Seven Stories Press.

Christina Jarvis

Christina Jarvis is Professor of English at State University of New York at Fredonia, where she teaches courses in sustainability and twentieth-century American literature and culture, including several major author seminars on Kurt Vonnegut. She is the author of The Male Body at War: American Masculinity during World War II, and has published in journals such as Women’s Studies, The Southern Quarterly, The Journal of Men’s Studies, and War, Literature, and the Arts. She lives near the shores of Lake Erie in Western New York.