Poetry From Honduras' Our Little Roses Home for Girls

Finding Joy and Forgiveness in Verse

Roberto Sosa, a well-known Honduran poet who died the year before I arrived there, said, “It is practically a poetic country. There are more poets than almost anywhere.” Our classroom starts to prove that boast. Local Honduran poets visit. The girls grow articulate and more confident. Poetry is not beyond them. The poems not only come out of their hands but memorized poems pour out of their mouths. One after another the girls recite and recite and recite. They recite Shakespeare for the board members. Not a dry eye among the businessmen and attorneys. The girls write poems first in Spanish, then translate them into English, or first in English and then in Spanish.

The girls are protective of their stories. Some are truculent, intractable, mercurial, stubborn. I realize their personal stories and the beds they sleep in are what they have, very often, all they have, so exposing that to strangers does not happen quickly, and sometimes it feels like it will never happen, and that, too, becomes fine with me. Exposing feelings is delicate surgery. They get grumpy and snappy. One girl writes, “It is horrible to know you’ve been thrown away.” Some of the girls will only publish anonymously—like Dickinson before them, the idea of publication horrifies them. It’s like “publishing your soul,” Dickinson had said. But Dickinson sent 575 of her poems out in letters. So a part of her wanted to be heard. This contradiction of being heard and not seen, this treading on very vulnerable ground in poetry, is something I intuitively understand. Often in my own writing life, I have felt a push and a pull between recognition and anonymity, and I think many a poet has felt or will feel the same. The soul needs protecting.

I start inventing assignments. The first assignment comes out of nativity figurines I find in the trash. These clay figures are called adornos. Each child picks one and writes in the voice of what she picks. One picks a cathedral, another picks a donkey, and yet another picks a headless woman. The poem in this collection, “A Honduran Story,” comes from Katherine staring at a clay wedded couple and imagining what they might say. The next semester I change tack and I ask the older children to write stories to the younger children. The girls only know one popular fairy tale called La Llorona which centers on an ugly deranged woman who kills her children and throws them in a ditch, so it seems there’s room for improvement. The girls invent new fairy tales with Honduran twists: Honduras and the five dwarves attacked by a witch represented by Spain.

*

On Mother’s Day Ana Cecelia, whose mother died of whose mother died of cirrhosis, hepatitis, and poverty, writes in her diary:

I don’t like poetry. But I enjoy the Literature class with Mr. Spencer anyway. The best part is when we spend time with the little kids. They talk about what they want to have in our “fable poems.” It surprised me to see how the little kids would open their minds and start imagining things. Today at the school we celebrated Mother’s Day. I watched the celebration and it was not bad at all. I noticed that the mothers who belong to the kids from the neighborhood were enjoying the program. It ended early. I felt nothing.

Loss looms large in our classroom, large as the blue mountains out the window. No amount of Christmas presents or sponsors in the States or gringos dressed up as Easter bunnies can cancel it out. Now you might think, as a result, everything I receive from the girls would be sad. But this is where things become more illuminated for me, more strange and intriguing. Nine times out of ten the poems come back with joy and forgiveness and hope. Leyli, beaten senseless by her mother, writes:

When I was six I saw my parents a few times, between one and four in the afternoon. I forgot their names. When I look up at the sky I do not wonder about them. I am going to play and I am going to dance to have some fun with the dark shadows. I will be a happy girl.

To the greatest horror, Leyli responds with whimsy. Next to the world’s worst barrio, a mural of a triumphant girl painted in electric hot pink and lime green and bright yellow.

*

Students have trouble with meter. After all, Spanish is accented differently and English rhythm is subtler. I want them to understand meter in Auden and Dickinson. One day trying to figure this out, I hear the sounds of salsa coming through my window. I ask my students how many beats are in salsa. Four, they say, usually, looking at me with teenage disdain for my ignorance. I say, “Perfect.” So it comes to pass, in chapel, my students dance and recite Dickinson’s “I’m Nobody! who are you?” with me in the background pressing down the salsa beat button on the electric piano. There is Dickinson, presented full blast with explosive movements before the school assembly that sits mystified in church pews.

Tick tock—my last days approach, along with mounting enthusiasm for poetry. we plaster the school hallways with poems. One girl, who is not in any of my classes and speaks no English, hands me a piece of paper crumpled into a ball, and says, “For you, Mister.” It will be the poem, “Invisible for All My Life.” Another day a girl from the home comes to me—one who had been stabbing her pencil into the sofa when we met privately and saying that poetry was boring. Now she comes to me and says, shoulder back, “Yes, Mister, I want to recite the Langston Hughes poem about Helen Keller.” When she does, she does so with more confidence than I’ve seen before. Where did it come from? For months she has not wanted any attention paid to her for being an orphan, has emphatically stated she wants her poem to be anonymous. After the Hughes recitation, she comes to my desk, looks out the window and says, “Hey Mister, I want my name in the book.” Gently, I tap the letters of her name onto the keyboard, and save the name into the document, a name she says she’s hated most of her life: Leyli Karolina Figueroa Rodríguez.

__________________________________

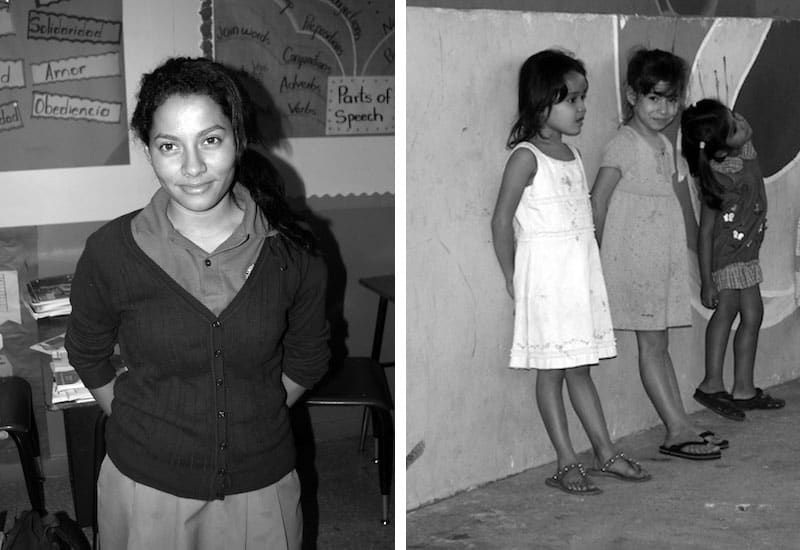

Photographs by Mary Jane Zapp.

Photographs by Mary Jane Zapp.

Invisible for All My Life

Paola, Age 18

I am an eighteen-year-old girl.

This girl has put up with being invisible all her life.

She didn’t ask to be the happiest woman in the world

but she did ask for someone to take care of her.

She never had the opportunity to have a family,

to receive love which is the only thing she wanted.

I don’t know if I’m in this world with love

or only that they were obligated to bring me into it.

It is awful to know you are a throw-away child.

I feel a hole in my soul and I don’t know how to fill it.

I know there are people that love me,

but is it true love?

Sometimes I wonder, I have had many opportunities to die…

Why didn’t I die in those moments?

Life doesn’t make much sense if there is no LOVE!!!

I will be a Happy Girl

Leyli, Age 16

When I look up at the sky my world is white. The wind blows the clouds. I want the world to be blue, like the ocean across the street in my imagination. I want my life to be fun like the girls I hear around on the street. My name is long and complicated. I don’t know who gave me my name. I don’t like my name. It is difficult to write.

I would like to be a psychologist because I would like to help many people. I do not have brothers or sisters. I have parents but I have not seen them in a long time. When I was six I saw my parents a few times, between one and four in the afternoon. I forgot their names. when I look up at the sky I do not wonder about them. I am going to play and I am going to dance to have some fun with the dark shadows. I will be a happy girl.

Photographs by Mary Jane Zapp.

Photographs by Mary Jane Zapp.

Little Rose

Aylin, Age 16

Little Rose, please close your beautiful eyes.

I can no longer bear to see the pain inside of them,

the pain caused by what I couldn’t prevent.

Waterfall

Aylin, Age 16

Waterfall, waterfall, wash my sins away.

Waterfall, waterfall, make the pain go away.

Waterfall, waterfall, make me forget.

Waterfall, waterfall, make me drown in your

precious waters.

Make me drown so I can no longer feel

the ferocity of my flesh being peeled

by the real me that is so tired of hiding inside.

Waterfall, waterfall, have mercy on me.

All photographs by Mary Jane Zapp.

__________________________________

From Counting Time Like People Count Stars by Spencer Reece, courtesy of Northwestern University Press. Copyright 2017.

Spencer Reece

Spencer Reece is an Episcopal priest and serves as the vicar of St. Paul’s in Wickford, Rhode Island. Author of The Clerk’s Tale and The Road to Emmaus, Acts, his third collection of poems, is recently out via FSG.