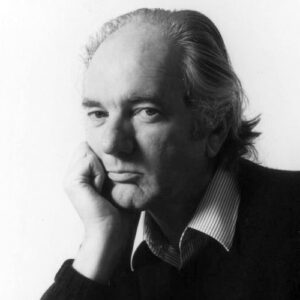

Poet W.S. Merwin Dies at 91

“We Must Want to Listen"

W.S. Merwin, whose singular poetic voice invited readers to contemplate the beauty and impermanence of the natural world alongside him, has died at the age of 91, his publisher Copper Canyon Press confirmed.

Born in New York City in 1927, Merwin found an early love of language in church as the son of a Presbyterian minister, writing his first verse in the form of hymns. He told Paul Holdengräber, founder of LIVE from the New York Public Library, in 2017 that he was struck, at a young age, by hearing his father read the sixth chapter of the book of Isaiah. “I was so taken by the sound of the language that I had memorized it just by hearing it,” he said. “I thought, ‘I have to find more language like that because I really want that to be part of my life.’”

He would later describe his childhood between Union City, New Jersey, and Scranton, Pennsylvania, as unpredictable and at times violent; speaking of his father to Dinitia Smith for The New York Times in 1995, he said, “I was frightened of him. There was a fair amount of physical punishment. I turned on him physically two times in early adolescence. I thought one time he was getting abusive to my mother. When I was 13, I said, ‘Never touch me again!’”

As a student at Princeton, Merwin studied under John Berryman and R. P. Blackmur. After graduating in 1948, his travels would take him through Europe before he landed in the south of France. Michael Wiegers described the beginning of his time there for Literary Hub:

Nearly 70 years ago WS Merwin, the two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and translator, was exploring the south of France when he came across a derelict stone farmhouse in the Midi Pyrenees region between Toulouse and Bordeaux. The rustic building, which was being used for drying tobacco, caught his attention less for its condition than for its location perched high above the Dordogne river, with views to the north and west across the broad valley below. This building and its surroundings would significantly influence his writing—and by extension much of American poetry—for decades to come.

His first published collection, A Mask for Janus (1952), was chosen by W.H. Auden for the Yale Series of Younger Poets award, even as some looked at his early work with skepticism; his verse, dense and inspired by classical forms, was seen as inaccessible. He would later draw Auden’s disapproval for donating his winnings from the 1971 Pulitzer Prize, for his book The Carrier of Ladders, to antiwar causes, a move that Auden criticized as a “personal publicity stunt.”

He came back to the U.S. in 1956 as a fellow at the Poets’ Theater, where he began to cast off his earlier style in favor of experimentation as he published further volumes, including Green with Beasts (1956), The Drunk in the Furnace (1960), and The Lice (1967).

In 1976, he moved to Hawaii, where he studied Zen Buddhism with Robert Aitken; soon after his arrival, he purchased a property in Ha’iku on Maui, a plot of land left bare after exploitative pineapple farming practices had stripped it of vegetation. Merwin would spend the following decades until his death expanding the property to restore that land to a lush palm forest. He married Paula Dunaway in 1983.

Merwin’s spare poems, devoid of punctuation and focused with a careful attention on small, passing moments, conveyed a hushed astonishment of the natural world and humans’ place in it. Dan Chiasson described his verse for The New Yorker in 2017 as “language scavenged from the elements, its power reckoned only as its meanings assemble, phrase by phrase, against the white of the page.”

Merwin described his process of composition as one of listening. “We must want to listen,” Merwin told Inescape Journal, a literary journal based at Brigham Young University, in 2012. “In reality, we already know how to listen. Children know how to listen—it’s an ability that we are all born with. Before we can speak we can listen, listening comes before speaking and even before seeing.”

Merwin’s work also drew on deep ecology, a philosophy that developed in the 1970s and aimed to re-contextualize humans’ role on earth as one life form among many instead of a dominant, extracting force. His work would often address the impermanence of human life, including in “Youth” from The Shadow of Sirius (2009), which won a Pulitzer Prize:

…only when I

began to think of losing you did I

recognize you when you were already

part memory part distance remaining

mine in the ways that I learn to miss you

from what we cannot hold the stars are made

Perhaps his most famous poem, “For the Anniversary of My Death” (1967), also expressed a sense of spaciousness:

Every year without knowing it I have passed the day

When the last fires will wave to me

And the silence will set out

Tireless traveler

Like the beam of a lightless star

Then I will no longer

Find myself in life as in a strange garment

Surprised at the earth

And the love of one woman

And the shamelessness of men

As today writing after three days of rain

Hearing the wren sing and the falling cease

And bowing not knowing to what

Merwin was also a prolific translator, having translated writers including Pablo Neruda, Federico García Lorca, Jean Follain, Roberto Juarroz, and Musō Soseki. His Selected Translations, 1948–1968 (1969) won the PEN Translation Prize. He also won the National Book Award in 2005 for Migration: New and Selected Poems and served as U.S. Poet Laureate in 2010.

After Merwin received the Kenyon Review Award for Literary Excellence that same year, Kenyon Review editor David Lynn asked in an interview how Merwin would describe what constituted “poetic wisdom.”

He responded, “The direct kind of wisdom would be commandments and things like that, I suppose, and I don’t think that is wisdom in the same sense. I think the indirect kind of wisdom is the interesting one anyway. It’s the thing, it’s the question. The wisdom should probably take the form of a question that you can’t answer.”