I was waiting right at the front door when she came in. She said, “Oh,” when she saw me, like she forgot I would be there.

“He’s in bed and we ate and watched TV,” I said. Images of Adam and the baseball. “He’s a good kid.”

She softened. “He really is.” There was a pause. “Do you drink whiskey?”

I thought at first she was calling me out and was relieved when she quickly laughed, shook her head. “That was stupid of me. You’re pregnant. Of course you don’t.”

I stared at a point just above her head. “Yeah.”

“Would you be okay watching me drink some?”

Back on Jenny’s couch, TV off this time. She drank straight from the bottle, a brand I’d only ever seen on the high shelves of the liquor store. Every time she lifted her arm to drink, her shoulder brushed against mine.

“You must think I’m the worst mom.”

“I don’t think that.”

“Well, I do.” She took a long pull. “Ask me where I was tonight.”

“Where were you tonight?”

“Drove around for a bit, wound up at the movies.”

I could feel her waiting for me to say something, waiting for me to judge her, and it wasn’t that I wasn’t angry. Picturing her in a dark air-conditioned room, popcorn on one side, Coke on the other, made anger bubble up inside me. I felt it stinging the back of my throat, thinking about her sitting comfortably while Adam and I sweated and threw. But then I looked at her next to me—the way she was gripping the bottle, how she stared down into it, like she was hoping if she stared long and hard enough the solution to her problems would appear in the honey-brown liquid—and the bubbling stopped and melted into a tenderness, hot and thick, and I mostly just wanted to be in that theater with her, hear her laugh at the funny parts. “What movie did you see?” I asked.

She choked on the drink she was taking, coughing whiskey all over her shirt. I watched a few drops dribble out the sides of her mouth. “That’s what you have to ask me? That’s what you gathered from that statement?”

“Is there something else you want me to ask you?”

“I don’t know, what about ‘How do you sleep at night?,’ ‘When exactly did you become such a selfish bitch?,’ or, better yet, ‘What type of mother leaves her child with a complete stranger for hours?’”

The bubbling anger in my chest started up again, more intense this time. “A stranger.” I said it one more time—“A stranger”—and the bubbling turned painful. “Is that all you think of me?”

“Fuck. No. Come on, that’s not what I meant. I was shitting on me, not you. You’re the best.” She scooted closer to me and took my hand in hers and I smelled perfume, something tropical, whiskey, and I marveled again at how quickly she could quiet everything—no bubbling, no mess in my head, just my hand and hers, she said I was the best.

“Did I ever tell you what I wanted to be when I grew up?”

“No.” I sat up straighter, squeezed her hand. “Tell me.”

“I wanted to be a farmer by day and a rock star by night.”

I laughed. “What does that even mean?”

“I liked cows and pigs and roosters and I wanted to play an electric guitar and be loved by millions.” She was smiling, and I felt as warm as if I had been drinking whiskey too.

“That’s awesome.”

“Well, it is and it isn’t. That was the last time I had a serious idea about what I wanted to be when I grew up.” She wasn’t smiling anymore, was back to looking at the bottle in her hands. “And I didn’t even try that hard to make any of it happen. The closest I ever got to a farm was through the window of a car on road trips up to San Francisco to see my aunt Frannie. I just liked how wide and green the fields were and how peaceful the cows looked munching on their grass. I took three guitar lessons and quit because it didn’t come naturally to me and I liked playing soccer better. There were lots of cute boys that played soccer.”

“You were just a kid.”

“Exactly! The last time I truly thought about my future and the mark I wanted to leave, I was eight years old. How pathetic is that? That’s how old Adam is, you know.”

“I didn’t know that.” He seemed both older and younger than that, and I didn’t know which was sadder.

“Yup, eight years old.” It was quiet for a moment, and then she was gripping my hand so hard I nearly cried out in pain. Her eyes were wide and brimming with tears that I was sure would burn me if they dropped onto my skin. “Every day, I am so afraid for him.”

I wanted to pull my hands from hers, but her eyes wouldn’t let me.

“The other day,” she said, “I was shouting at my husband for leaving all the towels wet after showering, and then he came up to me and said, ‘Mom, one day I’m going to invent a towel that dries in less than ten seconds.’” She took a drink and swallowed without making a face. “I mean, what the fuck? Ten seconds? He’s so sweet and bold, he doesn’t even pick a realistic timeline, skips minutes, goes straight to seconds. How’s he going to feel when he realizes that those ideas will only ever live in his head? My head’s a mess. Everywhere I go, I seem to find a way to trap myself. Most days, I can ignore it, but like anything you leave open and forgotten, it begins to rot. There are just too many thoughts, memories. I can’t look at anything and not think of something else.”

Jenny let go of my hand. There were white half-moons on my palm from her grip. “You don’t get it yet, but you will. Soon, you’ll have your own beautiful boy or girl who will look at you with their perfect little face and you’ll feel love and hope and, mostly, you’ll feel the weight of everything that’s ever happened to you and everything that will ever happen to them and you’ll want to run.”

The half-moons on my palm were fading and I dug my own nails into them, tried to get them to stay a little while longer.

I couldn’t stop looking at her hands. They held the bottle’s neck so tight her knuckles turned white. Just when I thought the bottle might break, her hands would fall limp. The air in the room was thick and sour.

Our words weren’t helping, falling out of our mouths and mixing terribly with the stink of booze, our sweat and breath. “Okay,” I said. “There are probably lots of little plots of land you could get for cheap.”

“What?”

“Like, for farming. There are still states that have tons of land and everybody eats corn, potatoes, strawberries, whatever else you grow in fields. It’s not too late to learn guitar. My neighbors have this old pit bull, Chulupa, who used to run and jump and slobber over anyone that came within a few feet of her. Now, after lots of training and liver treats, they say, ‘Hey, Chulupa, hey,’ and she’ll stop what she’s doing and sit straight up.”

Jenny didn’t say anything. I continued: “Adam could totally invent towels that dry in ten seconds. My—my friend was going to go to a big college and learn how to make video games. I bet there’s a school where Adam could learn about, uh, drying technology.”

“Did you just compare me to an old pit bull?”

“I’m sorry. I guess I did.”

“It’s okay. I like dogs.”

A buzzing sound started out of nowhere. I jumped, felt myself start to shake until I remembered that my phone was still in pieces. Jenny reached into her front jeans pocket and pulled out her phone, looked at the name on the screen, and slipped it back inside. She took a drink, and before she could even put the bottle back in her lap, my lips were on hers.

I’m sorry he leaves you here, traps you here alone in this house. I have phone calls I don’t want to take too. There’s a place I used to go when I felt lonely and small— not age-or body-wise small, I’m five ten in sneakers, I’m never actually small. But like when you’re in a people-packed space and there’s not a single face that looks at you for longer than a second—it’s not invisibility, it’s worse, they see you, they just have already decided in that second that there’s nothing about you that’s worth knowing, that kind of small. I liked sitting on the curb of the 7-Eleven parking lot. I’d get a Slurpee and sit a little left of the door so I could see all the people going in, but only their legs. A store across that street sold lamps, and it was always so, so bright.

Seconds passed without Jenny kissing me back. Seconds of she hates me, she doesn’t feel my thoughts. A second more and her lips were pressing against mine, even harder, and I wanted to take her to 7-Eleven.

I’ll get the cherry Slurpee, you get the Coke, we’ll sip and kiss and it’ll be fruity soda perfection. Bask in that lamp-store glow. You are beautiful and I will never make you cry, you will pick up every phone call from me on the first ring.

I wanted to take her to 7-Eleven. I’ll get the cherry Slurpee, you get the Coke, we’ll sip and kiss and it’ll be fruity soda perfection.

There was a fluttering in my stomach. At first, I thought it was just me and her—the softness of her lips, her hips melting into my hands—but then the fluttering was more insistent, something beyond me.

I stopped, put one hand against her cheek, took the other and pulled her hand from my neck, and placed it on top of my stomach. “Do you feel that?” I asked.

Kicking. It grew stronger with each breath I took. “Holy shit,” I said. “Do you feel that?”

Her eyes focused on my stomach. Billy had been deter- mined to be there for the baby’s first kicks, was always talking to my stomach, reciting facts he knew—red-worm composting is the key to a healthy garden; cigarette lighters were invented before matches; like fingerprints, every tongue print is different—but the baby had never responded before. Jenny’s touch made the kicking grow stronger, thuds from the inside that shook me.

__________________________________

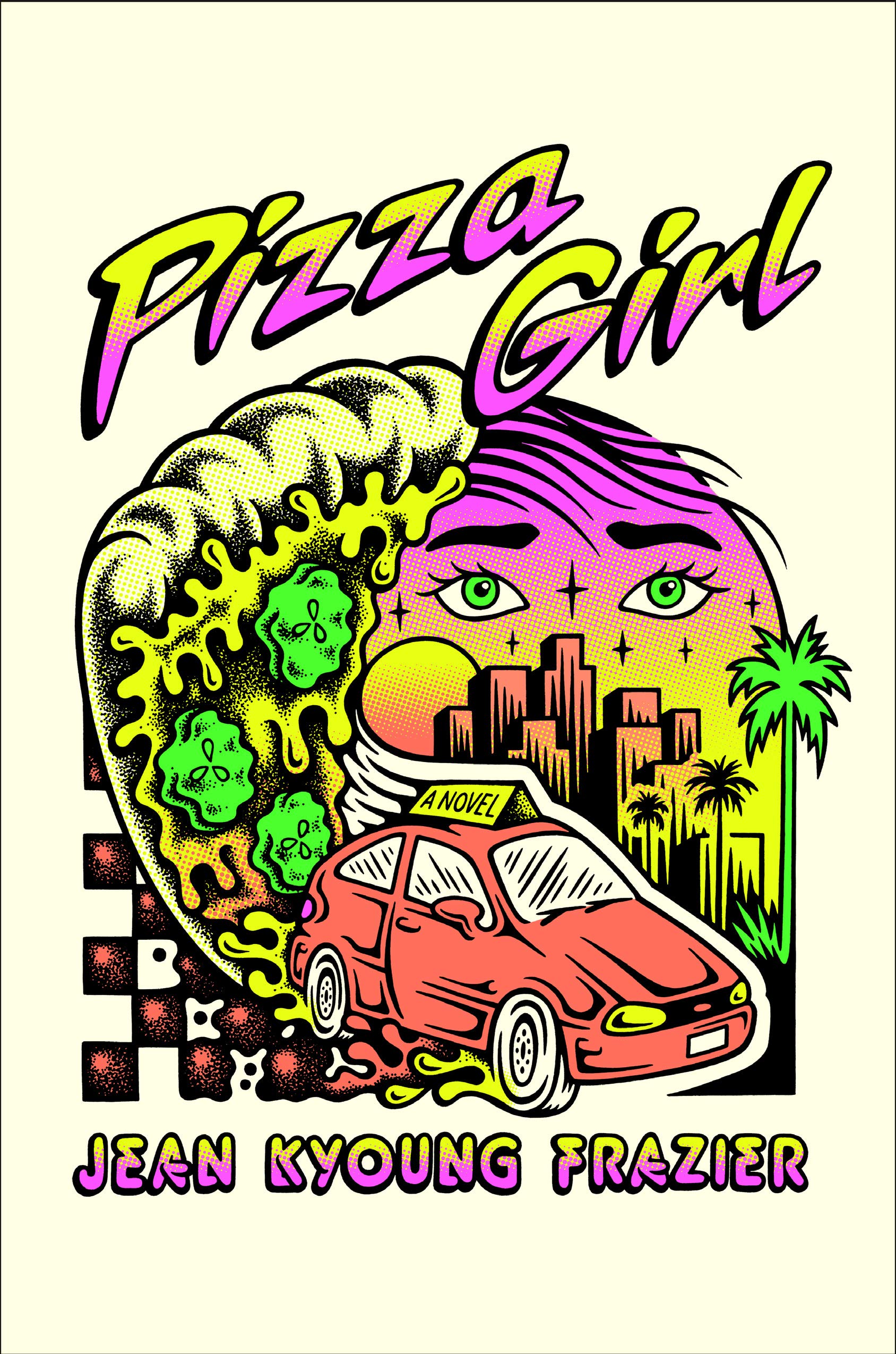

Excerpted from Pizza Girl by Jean Kyoung Frazier. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Doubleday, an imprint of Penguin Random House.