Pin-Ups First, Athletes Second: Sexism in Surfing

How Australian Surf-Lit Excludes Women

We crowded around the TV in a sweaty demountable and watched footage of the high school surfing team. I saw stringy boys in black wetsuits ride wave after wave; I was waiting for footage of me, which arrived unexpectedly spliced into the year ten boy’s semi-final, although I wasn’t surfing. I was emerging from the water and onto the shore—like girls I had seen in Tracks magazine—fiddling with my bikini and slowly walking toward the camera up onto the beach. I had no idea I was being filmed. There was no footage of me surfing. I was 13 years old. It was at that moment I realized who I was, or more accurately, what I was and it had nothing to do with surfing, but was intimately entwined with it.

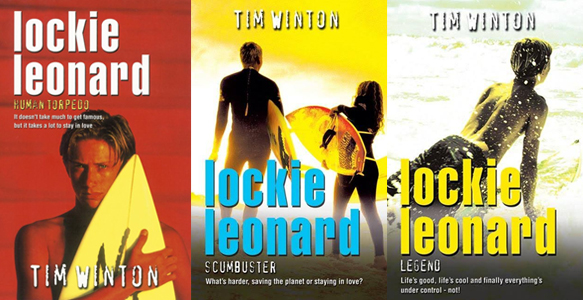

In high school I was a surf rat, like Lockie Leonard, the eponymous teen protagonist of Tim Winton’s young adult book series. We studied the books at school and followed Lockie as he navigated his way through shredding and acquiring a hot girlfriend. His world seemed familiar to me; shredding and hot girlfriends were the top priorities of most boys in my life. One formative moment occurred when these two interests collided: after school, my boyfriend paddled out to me in the line up and said, “You know we broke up, right?” (I didn’t know). “Yeah,” I said. Small tears slid into the salt water on my cheeks. He didn’t notice (thank god), because he was no longer looking at me. He had already snaked me and had priority for the next wave. I wasn’t his hot girlfriend, and I was not shredding.

Tim Winton has long been the literary mascot of Australia’s surfing culture for both the urbane literary set and surfers themselves. He has won the Miles Franklin award four times, he’s taught in school curriculums, his novels have been adapted for film and TV—he is basically Australia’s most beloved novelist. He has also become something like Aus-lit’s hippie guru. You can almost see his wispy locks in the brassy light as he drops perfect mantra quotes like, “I am at the beach looking west with the continent behind me as the sun tracks down to the sea. I have my bearings,” or, “Everything we do in this country is still overborne and underwritten by the seething tumult of nature.” Despite Winton’s ubiquity, there has been little critique of his depiction of women. Australia hasn’t questioned the repercussions of taking this masculine nostalgia as our most adored national narrative.

Growing up, I knew I could surf and I did. But I also I knew I could never be the surfers that were so carefully arranged on my school books and bedroom walls. Seeing that video of me in year eight taught me a profound lesson that I’m still trying to unlearn: although I couldn’t be the surfers I idolized, I could be desired by them (and in my home town that’s significant currency). In the narratives that surrounded me I could see girlfriends and hot girls—I couldn’t see me.

I’m not here to unpack why Australia fell so deeply in love with Winton’s world. His skill is obvious and his brand of wistful macho-romanticism is perfectly tailored to Australia’s literary mythos: man vs. bush (Banjo Paterson, Henry Lawson), man vs. farm-life (Les Murray) and Winton’s contemporary iteration—man vs. the surf (he’s a bloke, but he’s sensitive!). Australia’s perpetual need to look back to the sharpness of youth where the water was crisper and the girls were hotter is unsurprising. There is enough grit in the sentimentality and force in the narratives to make Winton’s tales feel real, raw and true. And maybe for some people they are true, but they are likely a white guy, and often they are your dad. My aim is to draw attention to how the male-centric nature of Tim Winton’s oeuvre perpetuates an Australian myth of surfing that, in reality, is unavailable to at least half the population.

Winton’s takes a Werner Herzog approach to nature: the ocean is indifferent and often brutal. “I love the sea but it does not love me.” If you dare wade into its waters, you can experience the sublime. If you are a woman the stakes are higher because if you are not brilliant you are the worst, if you don’t look good you are invisible, if men can see you they drop in on you. To surf big swell is hard—even with intense training my weedy boyfriend can pin me down, let alone the ocean! None of this is mentioned in Winton’s narrative. When Winton talks about surfing he talks about spirituality, contentment and a raw connection with nature. Winton’s tales of the surf are deeply solipsistic.

Breath’s narrator Pikelet recalls the experience of surfing as:

The blur of spray. The billion shards of light [. . .] I was intoxicated. And though I’ve lived to be an old man with my own share of happiness for all the mess I made, I still judge every joyous moment, every victory and revelation against those few seconds of living.

For Winton, to be in the surf is to be one’s true self, at your most authentic and free. It is the purest form of life.

*

I adore surfing. Many of my formative experiences occurred in the ocean (my first reo, when I did my first backhand slash, when I nearly drowned, when I spotted sharks, when my leg-rope got caught around a lobster pot, when I grasped a piece of swaying kelp and kissed a cute boy by a reef, etc.) Despite this, I never felt free, I never felt authentic and surf culture constantly reinforced it.

“There is enough grit in the sentimentality and force in the narratives to make Winton’s tales feel real, raw and true. And maybe for some people they are true, but they are likely a white guy, and often they are your dad.”

In Ways of Seeing, John Berger draws on the tradition of European oil painting to illustrate the difference between nakedness and the nude. He writes, “to be naked is to be oneself”: to be able to express yourself openly and be recognized for who you are. Winton’s surfers are “dancing themselves across the bay with smiles on their faces and sun in their hair.” He writes, “to see men do something beautiful. Something pointless and elegant, as though nobody saw or cared”—in short, they are naked. Berger elaborates on the distinction:

[T]o be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself. A naked body has to be seen as an object in order to become a nude. (The sight of it as an object stimulates the use of it as an object.) Nakedness reveals itself. Nudity is placed on display. To be naked is to be without disguise.

Winton assumes that all surfers are naked, that they are the embodiment of freedom. This assumption is why I bristle at his writing.

As I watched Ways of Seeing, I recalled the moment I saw myself on screen in year eight. I’m reminded of Erin Hortle’s essay in which she describes nailing a perfect ride only to hear her fellow male surfers say, “imagine seeing her do that in a bikini.” (A comment that no doubt many, many women have heard.) These are moments when we should have been able to be “naked.” Hortle should have been able to express herself with the same the unbridled delight as Winton’s surfers dancing across the bay and seen as who she is—a surfer.

Considering how elite female surfers are portrayed in the media, Berger’s observations are prescient. You may be world champion, but if you’re a woman you’ll be portrayed as a “nude.” Berger continues,

To be on display is to have the surface of one’s own skin, the hairs of one’s own body, turned into a disguise, which, in that situation, can never be discarded. The nude is condemned to never being naked.

There is something deeply unsettling in Berger’s description: the surface of your skin, the hairs on your body, are severed from you. They are transformed into a disguise by something you can’t control. You are stitched into a costume that is made from you: your face, your shape and skin, but it doesn’t belong to you. You are alien and yet yourself.

This might seem like a plot from a body horror movie but it’s just Steph Gilmore’s promotion for the Roxy Pro Biarritz—and the sad reality is that it could be any number of ad campaigns featuring female pro-surfers (e.g. Sally Fitzgibbons, Laura Enever, Coco Ho, Lakey Peterson, Sage Erikson). For Gilmore, the “disguise” is controlled and owned by her sponsor, who in return will pay the costs of competing on the World Championship Tour (which is estimated to be $40,000 a year) and more.

The Roxy Pro Biarritz promo is built from surfaces: skin in soft light with clothes sliding over it, water glistening on it, blonde locks falling onto Steph Gilmore’s back. As the camera documents each surface of her body, it replicates it and detaches it from her with the purpose of making it salable.

Alana Blanchard famously posed in a raunchy video with her boyfriend, Australian pro-surfer Jack Freestone for Stab Magazine. On the cover of the magazine she is featured kneeling in a blowup kiddie pool wearing stilettos while he squirts a garden hose nonchalantly in her direction; in the “short film” that accompanies the shoot she is in the kitchen, nude, with the exception of an apron; then she is in lingerie posing for Freestone who is on the couch and still mysteriously nonchalant. Stab captions a still of her in the film saying, “Ms Blanchard, the essence of beauty and marketability.” To recall Berger, “the sight of it as an object stimulates the use of it as an object.” Stab publishes intermittent “feminist” articles discussing the plight of female surfers, yet they are also publishing heinous sexualized content—at a much faster frequency than their pro-women content.