Three o’clock, the Campo dei Fiori. Morbidone stood under the rain, which cooled the stench of squalor. His back was against the blackened corner of a building, and he waited for the time to pass: the shutters of the Borgia cinema were still closed. He tired of standing still, kicked a banana peel, pulled himself up, and nonchalantly walked toward the statue of Giordano Bruno, which glistened in the rain. Some children were playing marbles. A group of little girls ran by, carrying red umbrellas.

How quiet it was! As slowly as the half hour that hesitated to pass, the rain rustled against the paving stones, exposing a combination of smells: anvils, dirty interiors, wet bed sheets. Morbidone’s expression was darker than the sky, which in the meantime had begun to clear. The Borgia’s shutters were raised with a crash at a few minutes before four o’clock; by that time an eager crowd had formed, and the sky was almost completely clear, its color a pale blue as tender as milk.

A few light clouds had run aground atop the façades of the dark buildings. Above the Palazzo Farnese, the sky was a fan of shadows.

Morbidone peered into the semi-darkened windows of a shop; it looked like a bedroom in the early morning, with the beds still unmade. But suddenly, what splendor! With his hands in his pockets, his tuft of black hair stuck to his forehead, olive-colored cheeks streaked with water, and eyes shining . . .

Morbidone had fallen into a trance, gazing upon this wonder of the Campo dei Fiori.

It was a sky-blue sweater. The sweater was large, meant for a boxer’s frame. Wide at the shoulders and chest, like a seascape, narrow at the waist. And the color! It was a light blue, both discreet and subtly alight. It would have been blinding in the sun on the Campo dei Fiori.

A wide yellow stripe divided the sweater into two vast areas, from the neck to the waist. Two equally yellow, but narrower stripes ran down the outside of the sleeves.

It was hanging on a hook in the middle of the shop window, as if standing guard, open wide, and its beauty obscured everything around it. Morbidone pulled himself away with a sigh; he walked back and forth in the Campo dei Fiori, paused in front of the newspaper stand, and bumped into Cravatta and Remo, who were off to the Piazza del Popolo, to sell bottles of perfume. But he could not stop thinking about the blue sweater.

He went back to the shop window to gaze at it. It was truly a marvel. “Ammazzalo,” he mumbled to himself, “Talk about the seven wonders of the world!” With the same dark look in his eye, he stepped into the shop and asked the old lady how much it cost.

“6,000 lire,” she said.

A few minutes later, the cinema opened. The housemaids, children, and young men who had been waiting outside rushed in and took their seats in the cinema which, half empty, echoed with their loud exclamations. Some of them smoked, their legs draped over the seat in front of them; others poked and shoved their friends. Morbidone picked up his tray and started to go up and down the aisles in the dark, dank cinema.

That night, the sky was completely clear. The stars were shining. The aroma of wet hedges floated down from Villa Sciarra and the Janiculum Hill, and the Tiber gleamed as it flowed under the glint of the stars.

Half asleep, Morbidone boarded the #13 tram, relaxed on the seat with his hands in his pockets, and was finally able to focus his thoughts completely on the blue sweater. The sweater enveloped his chest, magically doubling its strength and breadth. The boxing match had just ended and Morbidone had knocked out his opponent. He was wearing the sky-blue sweater, and the eyes of his pals gleamed with envy, especially Luciano and Gustarè. They went out into the street, and every girl had eyes only for him.

And then it was Sunday, at the beach at Ostia, or no, at the soccer game. The Roma team would win—to hell with Luciano and Gustarè—and he would wear his blue sweater and go dancing at the Trionfale, where his cousins went; he would dance with the most beautiful girls. The dream came to an abrupt end at the last stop on the tram line.

In the Donna Olimpia neighborhood, everyone knows everybody else. It’s like a small town. On his way home, he saw Luciano and Zagaja, who were talking about the game. He stayed out late with them. When he got home, his father had been waiting up for him, and the two of them got into a fight. His father hit him. Morbidone went to bed and decided that he would leave home the next day. He had 700 lire saved up.

By the following morning he had changed his mind: the 700 lire would be the first payment on the 6,000 he needed in order to buy the sweater. But his passion for the sweater had poisoned him. At noon he had another fight with his father, and so he decided to leave home once and for all. He would buy the sweater all the same, even if he had to steal for the money. The weather was beautiful again, almost as beautiful as it had been in August. There were people bathing in the river. “Good thing, too,” said the lupin-seller, “if I’m going to be sleeping under the stars.” He went to work at the Borgia, and finished late. He didn’t take the #13 tram, and didn’t return to Donna Olimpia. He found that he could daydream better as he walked. With the blue sweater in his heart, Morbidone slowly climbed the Janiculum hill and found a bench to stretch out on. But it was difficult to sleep on the hard surface! The splendid blue of the sweater kept him company in the shadow of the trees; through the leaves he could see the stars, and then the moon began to shine, in a golden halo.

Morbidone shivered from the cold, and sleep fell heavily over his chilled body. He awoke very early, when the sun was just showing over the horizon, infusing Rome with a dazed pallor. Two young men, wearing gray sweaters, blue pants with elastic around the ankles, and athletic shoes appeared on the deserted Janiculum. They started jumping up and down, punching the air, and running around the square. Morbidone watched them as they exercised, and when they started to walk down the hill, he followed.

The Campo dei Fiori was a circus: colors and exclamations flashing under the already burning sun. People yelled, protested, declaimed their wares; wheelbarrows, bicycles, and trucks crossed paths, in a festival atmosphere. Morbidone stole some fruit and ate it. Then he went to the shop window to gaze tenderly at his beloved.

–Translated from the Italian by Marina Harss

_________________________________________

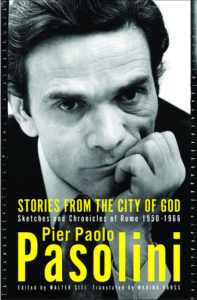

Excerpted from Stories from the City of God: Sketches and Chronicles of Rome 1950-1966, a collection of works by Pier Paolo Pasolini, edited in Italian by Walter Siti. Used with permission of Other Press. Translation copyright © 2019 by Marina Harss.

Pier Paolo Pasolini

Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975) was an internationally acclaimed writer, poet, critic, actor, director, and filmmaker. Among his most noted films are his epic masterpiece Accatone!, The Gospel According to St. Matthew, Teorema, and Marquis de Sade. He was the author of several novels, most notably The Ragazzi (Ragazzi di vita), as well as books of short stories, essays, and collections of poetry.