Photographing a New Era of American Leisure During the Vietnam War

Exploring the Disconnect Between a Country at War and Its Citizens

When I returned from Europe in 1967, after a year living in other cultures, America appeared very different to me. I saw how caught up the country was in consumerism and self-indulgence, how the Vietnam War was unfolding in front of us and people seemed to go about their lives as if it wasn’t their business. I saw how corporate America was creating an environment of distraction that seduced the majority of citizens into becoming a submissive body politic.

I applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship and asked for support to look at the way people spent their “leisure time,” that being a new concept in American life a mere decade earlier. But it was leisure time seen in the same frame of reference as the Vietnam War. How did the two relate and could I use photography to say anything meaningful about this attitude?

Courtesy and copyright of Joel Meyerowitz

Courtesy and copyright of Joel Meyerowitz

I was awarded the fellowship and took several road trips around America. Everywhere I looked the country seemed to be losing its edge, town centers were failing and malls were proliferating out in the suburbs, poor-quality buildings were going up on the outskirts of urban centers and little thought was given to the quality of life of the low-income people who were being pushed into them. Infrastructure didn’t seem to be keeping up with the demands being placed on it, or else the people who thought about planning these things couldn’t see far enough into the future to make them adequate for what was to come. Wherever I looked it all seemed to be coming apart in slow motion, so slow that it wouldn’t be seen until 20 years later when suddenly, after a couple of unsuccessful wars, America was no longer what it promised to be.

I noticed that everywhere I went in America the remnants and rejects of our military/industrial might were being recycled as ornaments at the entrances to small towns and parks, or dumped onto highway divides or traffic circles. The spent jets and cannons, rockets and tanks, replaced the doughboys of earlier wars and offered themselves up as icons of our material dominance of the world, objects of our pride, where machines replaced soldiers as our nation’s heroes. It seemed to me that this was a potential pairing with my notion of leisure time that could give the work some structure. No doubt I was influenced to some degree by the way Robert Frank used the American flag as a pacing element in The Americans (1958).

Courtesy and copyright of Joel Meyerowitz

Courtesy and copyright of Joel Meyerowitz

Courtesy and copyright of Joel Meyerowitz

Courtesy and copyright of Joel Meyerowitz

As I drove around the country I also picked up on the small moments of public violence, the little frustrations that everyday life contains, gestures and indications rather than large events of real violence, but they wove themselves into my consciousness and became part of the riff that played itself out wherever I found myself. With hindsight these images can be seen as artifacts from an era that represented a long, slow change in what America was.

Courtesy and copyright of Joel Meyerowitz

Courtesy and copyright of Joel Meyerowitz

It wasn’t easy taking on a challenge with the scale and complexity of American culture and geography, while at the same time trying to follow in the footsteps of a photographer I admired and whose work had become the giant monument blocking the road that all the young photographers of that time had to deal with. The issue of working around an influence was one that Harold Bloom, at that time a young literary critic, had written about in a provocative new book called The Anxiety of Influence (1973), about the ways the Romantic poets tried to resist being overcome by the influence of the poets who inspired them. Frank’s book, like the work of Kerouac and Ginsberg at the same time, was the great, dark poem of modern American life, the road movie of a book that inspired generations of photographers and poets to look hard at who and where we were at that moment in our history.

I believe that we all thought of ourselves as part of a continuum of the tradition of surveyors of the American landscape, not unlike Jackson and O’Sullivan one hundred years before us, but now we were the new generation who believed that a machine in one’s hands could be used to make the art of our time. So it was natural to pick up the traces of Frank’s lead and venture out into the wilds of America, camera in hand and hungry for experience.

I made a book dummy of the work with the title “Still Going,” as when someone asks you, “How’s that old car of yours?” and, though you know it’s a wreck, you might answer, “Still going,” which is how the country seemed to me as I travelled around it. Mired in an unpopular war, the country was limping along, but still going.

Courtesy and copyright of Joel Meyerowitz

Courtesy and copyright of Joel Meyerowitz

__________________________________

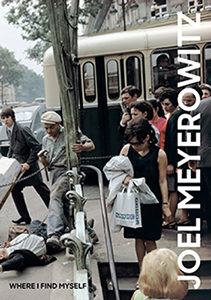

From Joel Meyerowitz: Where I Find Myself. Used with permission of Laurence King. Copyright © 2018 by Joel Meyerowitz.

Joel Meyerowitz

Joel Meyerowitz started making spontaneous color photographs on the streets of New York in 1962 with friends such as Tony Ray-Jones and Garry Winogrand. He has since become known as one of the most important street photographers of his generation. Instrumental in changing attitudes towards color photography in the 1970s, he is known as a pioneer, an important innovator, and a highly influential teacher.