The creek was made narrow by little green trees that grew too close together. The creek was like 12,845 telephone booths in a row with high Victorian ceilings and all the doors taken of and all the backs of the booth knocked out. RICHARD BRAUTIGAN

Even without booths, telephone conversations create locations, circumferences of absorption in which we sit, stand, circle, pace, gesticulate, think, and feel. Like the spaces we inhabit as readers, they are locations in which we are both here, and elsewhere—I can be staring something or someone, but if I am engrossed in the conversation I will see only an internal landscape, what is visible to me and no one else. Trying to retrieve the features of this landscape after the telephone call is over is a fool’s errand—it disappears as a dream disappears when we try to remember it.

But we were once much more tethered to the earth. The evidence was everywhere in the form of cords roiling in corners like snakes, or splayed across the floor like tripwire—from the receiver to the phone, from the phone to the wall, from the wall to the poles, from the poles to the switchboard. In the late 1870s and early 1880s, before Bell learned how to consolidate connections, there were so many phone lines weaving through the sky one could look up and see only slivers of blue. These lines were connected to a central switchboard run by thousands of mostly female operators, before the system became largely automated in the 1940s. Numbers came to include area codes, and area codes became, for some at least, a certain kind of identity marker. People in New York City and its boroughs, for example, were known to put up a good fight in order to retain Manhattan’ s “212” area code, even when they lived in an outlying borough like the Bronx or Queens. These were the days, which lasted well into the nineties and early aughts, when each of us knew at least two or three numbers by heart. Now many of us have area codes not from where we live now, but from some place we lived earlier—an earlier stage of life preserved in numerical amber.

Before many of us acquired the mobile phones we carry with us at all times, set beside our beds before we go to sleep, and pick up again when we wake up, our telephones occupied specific, intentional places where we lived. Perhaps the telephone rested behind a staircase, at the end of a hallway, or more centrally, on a desk in a living room or on a wall in the kitchen. Perhaps it lived at the juncture of the kitchen and the living room, or, as one friend described, while the telephone hung officially in the kitchen “with an epically long phone line,” it could stretch downstairs to the den, or around the corner to the dining room. In houses with multiple phones there was usually a hierarchy, the most important residing in the most central but least private place, leaving room for the “telephone paraphernalia” of notepads, pencils and pens.

Where a telephone was placed told us something about the person who had placed it, and maybe something about the lives they were living. One friend poignantly remarked that after her parents divorced there were so many moves and houses, the locations of individual telephones no longer stood out in her memory. Another wrote that in her house there were more and more phones as her brothers started getting into more and more trouble, requiring daily telephone calls to appease one harassed adult or another. Still another remembered that the family phone lived somewhere between the living room and the kitchen, “augmented with hella long ass handset cables—upwards of 10-15’ which could be extended to a desperate 20’ so you could watch MTV…Cordless was for fucking yuppie assholes who didn’t understand the relative value of stringing a 50’ cable.”

The telephone of my own childhood lived above the couch, kitty-corner from the bookcase, not a private space but its own space, and one that never migrated as Walter Benjamin describes the location of the phone in his childhood house migrating over the course of time to a more privileged place of attention: “The apparatus, like a legendary hero once exposed to die on a mountain gorge, left the dark hallway in the back of the house to make its regal entry into the cleaner and brighter rooms that were now inhabited by the younger generation.” Even when it inhabited the servant’s quarters of the hallway, however, Benjamin describes how the telephone “augmented the terms of that Berlin apartment with the endless passage leading from the half-lit dining rooms to the back bedrooms.”

The telephone’s ability to “augment the terms” of any space it inhabits is perhaps why the Japanese, in the early aughts, were working on technology to make phone booths able to transmit holographic images. It is also perhaps why phone booths have been variously appropriated by cinema as portals to other dimensions and time-travel machines to different eras. On March 31, 1999, the Wachowski brothers released The Matrix, a film that depicts a dystopian world in which humans have irrevocably damaged the Earth and “reality” is actually a simulation—the Matrix—created by code and energized by humans’ body heat and electrical activity. The hero of the Matrix is Neo, a young computer programmer who works in a nondescript cubicle in an anonymous city. Spending his off hours hacking into various computer systems, Neo is eventually recruited by Morpheus, the leader of a rebel force who has managed to escape the Matrix and who presents Neo with the alluring possibility of maintaining the status quo: “You take the blue pill, the story ends, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe,” or experiencing truth: “You take the red pill, you stay in wonderland, and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes.” Neo takes the red pill and awakens to the reality of his situation—that he and all the people he knows and sees exists in pods hooked up to a vast computer system. Morpheus and his rebel force live in an underground cell where the food is dismal and people are dressed in rags, a disappointing reality obviated by what Morpheus and his crew have learned how to do: master the Matrix and achieve autonomy in a world that is controlled by a computer program. Morpheus contacts Neo because he believes Neo is the one who will not only be able to see the Matrix for what it is, but also free everyone else from its clutches.

Although cell phones of a kind are present in The Matrix—both the rebels and the sentient machines use them to contact each other—the rebels can only enter and exit the Matrix through landlines, most often in phone booths. When asked why this was the case, the Wachowski brothers replied, “Mostly we felt that the amount of information that was being sent into the Matrix required a significant portal. Those portals, we felt, were better described with the hard lines rather than cell lines. We also felt that the rebels tried to be invisible when they hacked, that’s why all the entrances and exits were sort of through decrepit and low traffic areas of the Matrix.” At the end of the film Neo announces his intentions to the Matrix from a phone booth on a busy street: “I’m going to hang up this phone, and then I’m going to show these people what you don’t want them to see. I’m going to show them a world without you, a world without rules and controls, without borders or boundaries, a world where anything is possible. Where we go from there, is a choice I leave to you.” Although the sequel to The Matrix, The Matrix Reloaded, was released just four years later in 2004, phone booths were gone, already defunct as a means of communication and transportation.

Portals are elliptical passageways, eliding the journey between one place and another. In The Matrix this elision resonates with how Morpheus emphasizes that “reality” is really a matter of perception, easily manipulated if we are only strong and skillful enough to do it. Portals permeate everyday life now, but they are mostly in the form of websites, arguably the most mysterious and simultaneously most banal passageway we have. In contrast, landlines and phone booths were objects commensurate with the leaps people were making, akin to wardrobes and rabbit holes. As mysterious they were, these portals had heft, substance, materiality. For many of us, telephones were our initial portals to private lives, and, for those of us of a certain age, telephones were our first portals to the Internet, when we had to dial up the ether rather than be connected instantaneously and wirelessly. In 1995, when the Internet first came to widespread public consciousness via Netscape, Mark Thomas started a website called The Payphone Project where he listed hundreds of numbers from pay phones and encouraged people to call random numbers, creating chance encounters. Coincidences proliferate; meaning accrues. But when pay phones increasingly started to allow only outbound calls Tomas turned the website into a pay phone museum of sorts, gathering images, articles and stories that pertain to the public phone and thereby providing an invaluable archive.

The Tardis

The Tardis

Undoubtedly the most famous telephone booth is that used in Doctor Who, a British TV series in which a Doctor of Time travels through different eras in a repurposed British police box called a Tardis. An acronym for Time and Relative Dimension in Space, the Tardis is a piece of technology created by the Time Lords. One of the many capabilities of the Tardis is the ability to transform to suit its circumstances. However, the Tardis has a faulty chameleon circuit, and consequently has permanently taken the form of a 1960s British police box. Although it was probably cheaper to keep the Doctor’s time travel machine a police box rather than spending the money to develop a new one for every show, which ran weekly, the choice of a police box in the first place is significant. Jill Lepore finds a possible reason for it in the history of beat policing, which arose in nineteenth century England, when police officers controlled specific territories and developed strong relationships with the communities for which they were responsible. “Doctor Who polices worlds. The idea of a world’s policeman dates to the First World War and began to come into common usage near the end of the Second,” writes Lepore. “In 1943, during a birthday dinner for Winston Churchill, F.D.R. called upon the allied powers — the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and China — to serve as the world’s ‘four policemen.’” Doctor Who premiered in 1963, at the tail end of the British Empire and in the heart of the Cold War, a time when the efficacy of Britain as a “world policeman” had faded. The Doctor of Time is the closest thing Britain has to a superhero, but, unlike most superheroes, he feels the weight not only of personal history but the history of the entire universe he traverses so easily with the help of his telephone box.

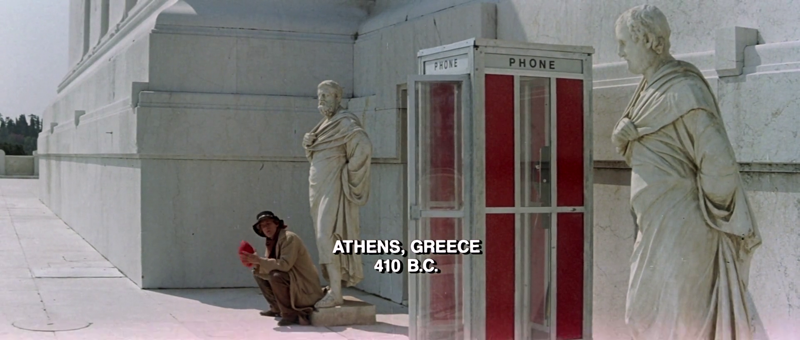

The decision for Alex Winter’s Bill Preston and Keanu Reeves’s Ted Logan in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure to travel through time from their home in San Dimas, California, in a phone booth was more circumstantial than symbolic—the director had originally planned to use a car but was worried about appearing as if he was appropriating Back to the Future—but the booth remains one of the movie’s most memorable and endearing features. Bill and Ted are in danger of flunking their history course unless they can deliver “something very special” in their oral report due the next day. Unbeknownst to them, the fate of the world depends on their successfully passing history and thus assuring the sequence of events that leads to the utopian society that exists in 2688. Consequently, Rufas, an emissary from the future, arrives in a phone booth to accompany Bill and Ted through time as they gather “research” for their presentation.

Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, dir. Stephen Herek, 1989.

Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, dir. Stephen Herek, 1989.

To a certain extent this repurposing of the phone booth offers one of the most accurate representations we have of what the phone booth actually means to us. Utterly quotidian, the phone booth nevertheless had the ability to transport us out of the world in which we were living. That this representation is offered in a film that has acquired a cult following among stoners and other refugees from the nineties tells us how deeply this understanding of the phone and phone booth really goes. What’s more, to see a glass and aluminum phone booth appear in Napoleonic France, the old West, or in ancient Greece is not much more anachronistic than encountering a booth on a street in contemporary life.

Rootlessness

Obsolescence has remade phone booths into real time-travel machines. Most of those that remain suffer the same fate as the Ramsays’ estate in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. Abandoned by the family, the house is overtaken by nature: “Only the Lighthouse beam entered the rooms for a moment, sent its sudden stare over the bed and wall in the darkness of winter, looked with equanimity at the thistle and the swallow, the rat and the straw. Nothing now withstood them; nothing said no to them.” The functional phone booths that interrupt stretches of the Pacific Coast Highway at regular intervals are perfect examples of how nature is reclaiming technology receding like deadfall back into the world from it sprung.

A few miles south of Bodega Bay, where Tippi Hedren’s Melanie Daniels famously sought shelter in a phone booth from an ever-increasing flock of venomous birds, is a phone booth that sits beside a restaurant looking out to the Pacific. Rust has corroded parts of the back panel that was once a deep sky blue. On one of the outside corners, a handmade sticker for Doomsayer is peeling back from its edges and various hieroglyphs have been scrawled across amenable surfaces. Sea grass and weeds are growing up through the cracks in the cement base, finding their way in the gap between the walls of the booth and the ground. In the distance, a lone schooner floats against the horizon, perfectly framed by the glass panes of the booth. The manager has been embroiled in a persistent battle with the telephone company that wants to remove the phone because it has long since stopped making anything close to a profit. “It’s true, it costs more money to maintain than it makes,” he tells me when I ask him about the booth, “but this whole stretch of the PCH is a dead zone. That phone booth is a civic service.”

When people discuss the consequences of the disappearing pay phone, though, the two groups that come up most often are immigrants and the homeless, categories of people defined by their relationship with place, or lack thereof. “Pay phones are lifelines for the down and out,” Mark Thomas commented to the New York Times, “their booths are rainy-day cocoons,” he said. “You lose those, and you lose a lot of windows onto the human condition.” Although the number of working pay phones available in the United States continues to rapidly diminish, many remain in areas with high immigrant populations such as Columbia Heights in Washington, D.C., or East Los Angeles. The advertisements that cover the surfaces of these pay phones tend to be for prepaid international calling cards as much as for taxi services and call girls. According to Robin Harris, the president of Robin Technologies, a corporation that owns and operates pay phones in the Washington, D.C., area, “Immigrants are one of the niches that the pay phone community serves very well. If someone wants to call home, say to El Salvador, it can actually be less expensive for them to use a public phone than a cell phone.”

Most homeless people do not have access to any telephones but public ones, and yet no provision has been made for them in the event of pay phones being removed entirely. In 2011, Contexture Design, a design firm based in Vancouver, B.C., released a repurposed phone booth that contained shelves, a radio, a sink and a seating area that unfolds into a bed. Contexture’s website explains the project as an “exploration of shelter and the concept of home, particularly as it relates to homelessness,” while it also emphasizes that their repurposed booth is not a “realistic solution.” Nevertheless it does acknowledge the fact that for many homeless, the phone booth is far from dysfunctional.

Contexture’s redesigned phone booth is a practical response to its increasing obsolescence, but most repurposed phone booths do not strive for practicality, perhaps because phone booths were marketed as tools of convenience and emergency, but always as tools, emphasizing what Martin Heidegger might have deemed their “readiness-to-hand.” When we use a phone booth we don’t interrogate its identity; we simply use it, more or less automatically. It’s only when an object breaks, or is otherwise rendered useless, that it becomes characterized by something other than its utility. The graffiti artist Banksy made this point quite well when he installed a broken phone booth on a street in Soho. Knocked on its side, broken nearly in half, a pick ax sticking out from one of its walls and blood spilling from beneath it, Banksy illustrated the willful murder of the phone booth.

We are now much more likely to encounter a phone booth in which we can call someone to hear a poem, or the recording of a beautiful violin concerto, than we are a phone booth in which we could call our spouses. In 2008, the one phone booth and mobile lending library disappeared at the same time from Westbury, a small village in the county of Somerset, England. Instead of letting it go, the residents collectively bought the phone booth and turned it into a lending library. (The project was repeated in 2012, when the architect John Locke began to turn abandoned phone booths throughout New York City into lending libraries.) In 2011 Kingyobu, (the Goldfish Club) repurposed a group of abandoned phone booths as goldfish aquariums and started installing them around the city of Osaka. A phone booth in Yellow Springs, Ohio, was the site of twelve different art installations between 2009 and 2010. The Wi-Fi hotspots all but three remaining pay phones in New York City will become—which look like enlarged smart phones—are called “links.” So the portals remain, but they are taking us to different places, or perhaps they are the same places strangely configured.

From PHONE BOOTH part of the Object Lessons series. Used with permission by Bloomsbury Publishing Inc. Copyright © Ariana Kelly, 2015.