Permanent Newness: Surrealism at 100

Mark Polizzotti on the Legacy of One of the 20th Century’s Most Innovative Artistic Movements

Does Surrealism still matter? Has it ever mattered? The question is hardly new, and has been debated practically since the movement was launched. Already in 1930, a mere six years after its brash inauguration, the twenty-something poet René Daumal was cautioning André Breton, Surrealism’s founder, primary theorist, and author of the Manifesto of Surrealism (1924), against the threat of irrelevance through popular acceptance: “Beware, André Breton, of one day figuring in study guides to literary history; whereas if we aspire to an honor, it is to be inscribed for posterity in the history of cataclysms.” (An apt warning, as Breton and many other Surrealists have since figured in quite a few study guides.)

A dozen years later, Breton himself, in exile in the United States during World War II, fulminated to students at Yale University against the “impatient gravediggers” who declared Surrealism over and done. Given that many of the young men in the audience were thinking about their looming draft notices, we can imagine that they, too, were wondering how relevant Surrealism was to their lives at that moment. And today, as Surrealism marks its centennial, and as its fortunes over the past fifty years have risen, fallen, and risen again, it’s a question worth pondering once more.

Indeed, much like the students at Yale, young people of the twenty-first century could hardly be faulted for wondering what a bunch of eccentric writers and artists showing off their dream states could have to do with such pressing concerns as social and racial injustice, a faltering job market, gross economic inequities, the decimation of our civil liberties, questions of gender identity and equality, environmental devastation, education reform, or, once again as I write this, the specter of world war. All the more so in that the word “surreal” has come to stand, in the popular imagination, for a vague cluster of things, a catchall term that runs the gamut from the unnerving to the merely kooky.

Surrealism’s importance lies not so much in the works it produced as in the attitudes underlying them.

The answer is that Surrealism engaged with all of these crises. To cite several examples: The Surrealists’ outspoken critiques of French colonialism and racism share many points in common with current debates about racial equality and social justice. Their opposition to war and the military, dating as far back as World War I, was echoed in protests against France’s involvement in Algeria and America’s war in Vietnam, among others. The frankness with which they addressed sexuality, though this does not airbrush the more than equivocal position of women in the movement, was audacious for its time, and has had lasting echoes in contemporary attitudes. Their skepticism about work is almost a direct pre-echo of today’s Great Resignation.

In addition, their unflagging resistance to the constraints preached by the double act of Catholicism and bourgeois morals helped pave the way for our more secular, comparatively less regulated, times. And their challenge to the rigid, rote-based educational system used in France for much of the twentieth century predates the pedagogical reforms of Piaget and Montessori. Little wonder that the Surrealist declarations spray-painted on the walls of Paris during the May 1968 student protests, though they had been coined more than forty years earlier, sounded as if freshly minted.

Even those unaware of Surrealism’s influence on aspects of our social and political existence acknowledge the movement’s impact on everything from fine art and literature to advertising, design, and popular culture. Without the Surrealist concept of “black humor,” for instance, it’s difficult to imagine the Theatre of the Absurd, Monty Python, the cinema of David Lynch, or any number of recent and current film and TV offerings.

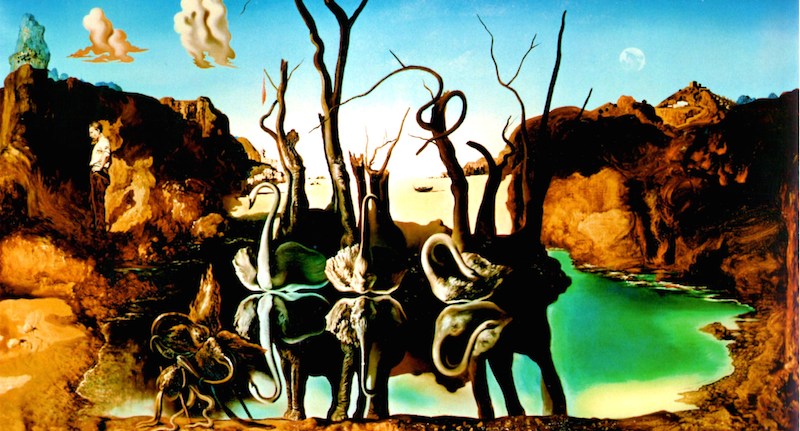

The group’s practice of automatic writing feeds directly into the work of Bob Dylan, the Beats (especially William Burroughs’s cut-ups), the New York School poets, and many others in their wake. Their art exhibits and demonstrations forecast the later emergence of performance art, installation art, and multimedia constructions. And Surrealist-inflected imagery has gotten so prevalent that it doesn’t so much fade into the landscape as become the landscape.

Still, merely being a precursor is not enough. To my mind, Surrealism’s true legacy is less as a forerunner than as a disruptor, something that perpetually challenges the existing paradigms and seeks new forms to maintain its emotional intensity. Or again, as a code-mixer, which takes in elements of its past, present, and projected future and recombines them, reworks them, reimagines them into something new, and then something newer.

While some members’ actions and attitudes might seem less than satisfactory, especially by current standards (which themselves will be reevaluated by future generations), I believe that their involvement with the issues listed above has much to say to the present moment, in what they got wrong as much as in what they got right.

One of Surrealism’s main drivers was a refusal of the values that European society tried to force on them. As political beings, they abhorred the bellicose jingoism that came screeching to the forefront during the War of 1914-18, and they felt revulsion not only toward the war itself but also toward the societal status quo that had fostered it, as well as the economic disparities, blatant racism, and intellectual blandness that went with it.

As writers and artists, they repudiated—at least in theory—the careerism and complacency that underscored so much literature and art, and that led to creative stagnation, not to say to a tacit or overt endorsement of the crumbling social contract. By nature, Surrealist works are animated by an emphatic dissociation from the reigning orthodoxy, whether political, societal, or aesthetic.

The means by which the Surrealists sought both to reject the Western world’s menu of choices (its murderous oppression as well as its brain-deadening banality) and to infuse human life with a higher and more consequential meaning followed several main avenues: the search for marvels, whether through automatism, unconscious states, or the exploration of chance and coincidence; the emphasis on humor and play; the elevation of desire and sexuality into a revolutionary force; the constant search for new expressive forms, along with the transmutation of ordinary objects into objects of desire; and the reimagining of political activism not as a basic wage-and-labor program but as a much more wide-ranging liberation of the human mind.

Of these, the aspect of Surrealism that to me epitomizes why it continues to resonate through changing trends and urgencies is its unwavering belief that the marvels it sought were a force for universal emancipation, within everyone’s reach. The aim was to tap into previously unsuspected resources and unleash the potential we all possess for wonder, invention, and salutary rage.

Otherwise put, Surrealism’s importance lies not so much in the works it produced as in the attitudes underlying them. Those who equate the movement with names such as Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró, Yves Tanguy, Paul Eluard, and Robert Desnos might find this surprising. But though Surrealism is now generally considered a movement in literature and the arts, and while its principal members indeed used artistic means, their initial impulses were mainly philosophical, political, and experimental.

Breton, a former medical student who had studied neurology and psychiatry, defined it with scientific tonalities as “psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express… the actual functioning of thought.” Surrealism in its essence tends not toward aesthetics but toward a radical new means of seeing the world, even a set of ethical guideposts.

Surrealism posited a world that could embrace, equally and indivisibly, the violence of rebellion and the passion of creation.

To take this one step further, it has often been charged that, when compared with such currents as Impressionism, Cubism, or Expressionism, Surrealism yielded relatively few iconic artworks—a view most notably posited eighty years ago by Alfred Barr, Jr. in the catalogue to his 1936 “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism” show at the Museum of Modern Art: when Surrealism stops being “a cockpit of controversy,” writes Barr, “it will doubtless be seen as having produced a mass of mediocre pictures… a fair number of excellent and enduring works of art, and even a few masterpieces.”

It’s true that for every melted watch and fur-covered teacup, for every Nadja and Paris Peasant and Chien andalou, there are hundreds of books and visual works that seem at best derivative, at worst frankly pedestrian, the stuff of which parodies are made. But is that the point? Without these so-called lesser works (and who’s to judge?), we’d have a much poorer illustration of what Surrealism engendered, what it inspired, and what it made possible.

One of Breton’s many attempts to encapsulate the movement’s wide-ranging goals was: “Transform the world, change life, refashion human understanding from top to bottom.” This is admittedly a tall order, but one that arguably has kept Surrealism from ossifying into an artifact, to be dusted off every few years, set on an exhibition shelf, then shoved back in the drawer.

As it happens, that last assertion has been given a regrettable and unexpected opportunity to be tested: Conceived shortly before Covid-19 upended the world and composed in the years that followed, this book was written against a backdrop of upheavals that included a global pandemic and its resultant social disruptions; the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and too many others; an ongoing reckoning (or lack thereof) with legacies of racial injustice and gross economic disparities; stark political polarization in country after country, with the attendant specter of increasingly autocratic regimes; and, as I write, the catastrophe of war in Ukraine.

Surrealism emerged under disturbingly similar circumstances, spurred by the carnage of World War I, fueled by the political and social unrest that followed throughout Europe, and haunted by the Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918–20. Its legitimacy and relevance were called into question many times over the following decades, and it was all but eclipsed by the advent of the Second World War and the subsequent Cold War, and by the threat of nuclear annihilation that we have in no way eliminated, merely incorporated into our daily existence. Is it coincidence that the movement is now experiencing a resurgence of interest, as evidenced by the stream of recent publications and exhibitions highlighting it as both a historical and contemporary phenomenon?

When René Daumal laid the accent on the “cataclysmic” aspect of Surrealism, rather than on the writings, paintings, films, and other artifacts it was busily producing, he foresaw a crucial but, at the time, little-recognized truth: that the permanent newness and effectiveness of the Surrealist message will depend on its continued capacity to respond to the upheavals forced upon it and incite its own upheavals in return, rather than its ability to fabricate art or literary objects.

More than any other intellectual current of modern times, Surrealism posited a world that could embrace, equally and indivisibly, the violence of rebellion and the passion of creation. This book aims to parse out what is living and what is dead in Surrealist ideas, what is vibrant and what stale; to evaluate why, and whether, the revolution that Surrealism sought to foment can still claim the qualifier, as one of its tracts put it nearly a century ago, of “first and always.”

__________________________________

From Why Surrealism Matters by Mark Polizzotti. Published by Yale University Press in January 2024. Reproduced by permission.

Mark Polizzotti

Mark Polizzotti is an award-winning writer and translator. His previous books include Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton and Sympathy for the Traitor: A Translation Manifesto, as well as many translations from the French.