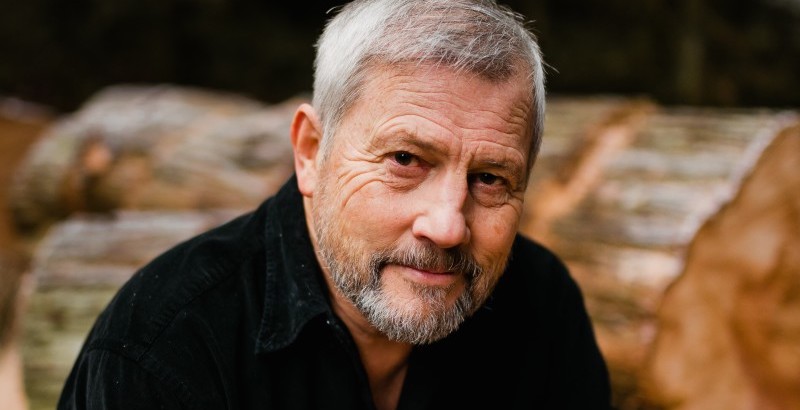

Karl Marlantes on Chronicling the Early Cold War Years

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of “Cold Victory”

Karl Marlantes’ Matterhorn, published in 2010 and based on his service as a much-decorated Marine during the Vietnam War, has become a wartime classic, linked with All Quiet on the Western Front. In Deep River, his second novel, Marlantes, whose maternal grandparents came from Finland, wrote about Finnish immigrants to the U.S. during the early years of the twentieth century.

His new novel, Cold Victory, combines his visceral sense of wartime with a sophisticated awareness of Finnish culture and terrain and the complexities of postwar diplomacy and intelligence gathering in a country that was nearly absorbed into the Soviet Union. His narrative is crisp, empathetic, and highly visual, beginning with the opening lines: “She’d followed Arnie Koski a long way from Edmond, Oklahoma. Louise Koski was now standing on the open passenger deck of the Stockholm-Turku ferry as it formed a channel through the thin, early December ice leaving floating shards reflecting the wan sunlight in its wake. The angle of the somber sun in a clear comfortless sky was only a held-out fist above the southern horizon.” Our email conversation was effortless and swift.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have your life and work been during these turbulent times? Were the writing, editing and launch of Cold Victory affected by the pandemic?

Karl Marlantes: Thankfully, I haven’t been much affected, personally. I think Dylan Thomas once said something like “writing is a lonely and sullen craft.” So, I tend to keep myself in self-imposed quarantine all the time.

JC: What inspired you to write about the immediate aftermath of World War II, years 1946-1949 in Finland, a country that was invaded by the Soviet Union, losing huge amounts of its eastern territory. After the war, Finland fell under Soviet dominance and teetered on the edge of becoming totally absorbed into the Soviet Union, an outcome that would have been calamitous for the U.S. and a Western Europe struggling to stay free.

I also have despaired at our own citizens’ lack of understanding of just how privileged we are.KM: I started writing the novel several years after the West’s tepid response to Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine. In February 2022, well after I’d started writing Cold Victory, Putin attacked again. I think the West’s timidity and naiveté, and I might even suggest cowardice, after the 2014 invasion, greatly influenced Putin’s decision.

I set the novel just after WWII because I saw that the historical situation between Finland and the Soviet Union then was very similar to what Ukraine and other Eastern European countries face now. As you must know from my previous books, I’m no lover of war. I do, however, believe strongly that there are times when wars need to be fought.

Usually, wars happen when the unbridled ambition and narcissism of some people in power are not checked by clear signals about the consequences of defying established rules of international cooperation, backed up with credible military force. Europe was totally naïve about Russian ambitions, particularly Germany, which got hooked on Russian energy. It and many other countries freeloaded for years off the few who were spending to maintain a credible deterrent force. Although the United States was one of those doing the spending, it was wasting its deterrent force on dubious engagements in Afghanistan and Iraq.

I also have despaired at our own citizens’ lack of understanding of just how privileged we are to have rule of law, privacy, freedom of expression—all the rights delineated in our founding documents. I think we are dangerously close to losing them, not just to external threats, but to our own foolish disregard of what it takes to keep those rights.

If I can paraphrase Martin Luther King, Jr., we will never permanently defeat the forces of fascism and repression, but each generation must fight to keep them in check. I don’t think it will be difficult for readers to see that what Mikhail and Natalya are forced to suffer under a totalitarian government, we are doing to ourselves.

JC: Why did you decide to make your primary narrator Louise, an Oklahoma-born woman who arrives in Helsinki with her husband, Arnie Koski, who is serving as military attaché to the American legation there, gathering military intelligence?

KM: Louise’s character represents my view of most Americans: energetic, big-hearted, go-getters, but very naïve about the world outside of the United States. I think most Americans are increasingly ignorant of the fragile institutions that keep us safe and free, which wasn’t the case in 1947.

Close to 300,000 young Americans died defending those institutions and nearly everyone knew it and believed their sacrifice was worthy. I picked Oklahoma because it is in the heartland, and in the 1940s was even more isolated from the rest of the world, both geographically and culturally, than, say, New York or Massachusetts.

JC: How were you able to infuse Louise with such energy and naivete?

KM: I’d guess by showing, not telling. I was aware that making her so naïve might stretch credulity, but I stand firm. People who think she is too naïve, are naïve. We have members of Congress who are no smarter than oysters and as ignorant as medieval peasants—and American voters put them there.

As for Louise’s energy, people like her get things done. They are all around us. I just thought of my own mother, who left school when she was 14 and worked waiting tables and bookkeeping and bought us books, bicycles, and music lessons, at the same time managing to keep my brother and me from killing ourselves under the influence of a drug called testosterone.

JC: The secondary couple in Cold Victory are Mikhail, a much-decorated Red Army lieutenant colonel with a Hero of the Soviet Union medal, and his elegant and war-weary wife Natalya, who survived the siege of Leningrad. You weave a connection between Arnie and Mikhail, who had met briefly on along the Enns River in Austria during the war, celebrating that moment of allies meeting on the battlefield with a bottle of brandy. How common are such experiences with allied troops?

KM: Meetings between allied armies are very common between advanced elements. April 25, 1945, is the day Soviet and American troops met at the Elbe River, near Torgau, Germany. There were numerous publicity photos showing Russian, English, Canadian, and American soldiers with Red Army soldiers.

I worked in India in the 1980s and one night was happily accosted by a drunk Russian arms seller who showed me his watch which had been given to him by an American soldier he’d met when the two armies made contact, sealing the fate of the Wehrmacht. Even enemies have met, although much more rarely. The most famous example is the spontaneous Christmas truce of 1914 when English and German soldiers sang carols together and played soccer.

JC: What sort of research was involved in tracing the fraught relationships among the Finns, the Americans, and the Soviets in Helsinki at that time?

KM: I have been interested in WWII my entire life, particularly how it affected Finland and Greece, my grandparents’ native countries. My father landed at Utah Beach and fought in the Battle of the Bulge, all my uncles also served, as well as the fathers of my close friends. So I had considerable background and only needed to fill in details which I did through a lot of reading about the time. I also was helped by Finnish friends who are historically savvy and kept me straight. I thank them in the acknowledgments. Then there is good old Wikipedia. I contribute.

JC: The spine of the book is the 500-kilometer ski race between Arnie and Mikhail, spurred by a drunken challenge at a Soviet embassy party, set to take place in arctic Northern Finland, where daytime temperatures hover around zero, and the nights are “brutal.” How did you go about creating the details for such a complicated race?

I think most Americans are increasingly ignorant of the fragile institutions that keep us safe and free.KM: I grew up on the Oregon coast in a small logging town and spent a lot of my childhood in the woods. If I walked due east from my back porch, I wouldn’t hit a paved road for 16 miles. It was also a hunting culture, so we boys had a lot of common sense drilled into our heads about how to survive in the woods if we got lost.

When I was younger, I did a lot of off-trail skiing in the Cascade Mountains. I also had a secret weapon, my friend, Marcus Prest, who is a Finnish Marine and has spent thousands of hours patrolling on skis in the wilderness along the Finnish-Russian border. He mapped out the entire race between Arnie and Mikhail.

JC: Louise and Natalya, who are able to communicate in French, get involved in fundraising for a Finnish orphanage—a project Louise, who has no children, sees as a joint good-will effort between the Americans and the Soviets. Natalya, the mother of two, who was raised in a Soviet orphanage, understands the project as a hopeless drop in the bucket for orphans from the war, with the potential for disaster. Louise’s intuition said Natalya was a friend, but, she muses, “how could she trust her intuition in a world filled with disinformation and deceit?” How did you skew these two characters to exemplify the contrast between American and Soviet perspectives in that era?

KM: I made it clear that Natalya had suffered greatly during the war, and Louise had not, just as the people of the Soviet Union suffered greatly and Americans hardly at all. The leaders and the people of the Soviet Union would do nearly anything to avoid such suffering again, hence the expansion into eastern Europe and subjugation of Eastern European people. This was a brutal solution to Russian security problems but undertaken with few qualms. Americans—whose equivalent safety barrier was two oceans—never had to make a hard choice like that, making it easier to be more scrupled.

Soviet expansion into Eastern Europe was most certainly cruel and immoral. But in the minds of most Russians, that cruel expansion was justified. In addition, the fact that Eastern Europeans lost most of their civil liberties was of little consequence as they were living no differently than Russians. I also show how Natalya must guard her every word except when she’s sure she’s alone with Mikhail. Louise has no privacy issues—until she’s suddenly thrown into Natalya’s everyday reality.

JC: “To win it would come down to heart—and what one was willing to risk,” you write of the race. Is sisu what it takes? My half-Finnish husband Mark has long spoken to me of sisu. Arnie refers to sisu from time to time. Can you explain the concept, its history?

KM: Sisu is nearly untranslatable, which is why it is used in the Finnish even when speaking English. It is different than heart, but it includes heart. It has the sense of the English expression, “bloody minded.” It has to do with “sticking to one’s guns” in the face of adversity that those without sisu would say was unreasonable. The best way to explain it is examples.

If I fell down when I was a child and started to cry, my mother would ask, “Where’s your sisu?” or say, “Find your sisu.” She’d expect me to get up, ignore the pain, and most importantly stop crying. I’m not saying that’s all good, but it breeds really tough fighters. It is also something that one finds within themselves, like it is highly individual and expressed individually, although the net effect of all this is a national character. I asked my grandmother once what sisu was. She paused only a moment and said, “It’s what beat the Russians in the Winter War.”

JC: What are you working on now/next?

KM: I’ve got a couple of articles to write immediately, one as a response to an article about being a sniper and the other about my recent return to where I fought in Vietnam. My next novel is tentatively called In the Shadow of Saddle Mountain. It is set in the same time and place as Deep River only it involves Greek merchants, revenge killing, and government corruption.

__________________________________

Cold Victory by Karl Marlantes is available from Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic.