1.

The Human Skin is made up

of three layers: Epidermis, Dermis,

Hypodermis, and here, at the base,

legitimacy already comes into play.

You see, the Epidermis seals the body from

intrusive outside influences. The Dermis

houses scars from breaks in that seal (and

tattoo ink, if that’s your thing), and its

darkness is determined by the

accumulation of melanin, the body’s natural brown ink,

richer in response to environment.

The Hypodermis is said not to be

a true layer, a lying layer, as it were,

made of insulating fat and connective tissue.

The Apple Skin’s color is determined by

the accumulation of anthocyanin, its natural

red ink, also richer for environmental influences,

but it does not have the same luxury as human skin—

its covering, an easily bruised and battered thin layer.

Metaphorically speaking, this weakness is perhaps

why the Apple is the fruit so often depicted as Eve’s edible

error of assertiveness, her knife-keen desire for knowledge.

The Apple, tender and vulnerable, is the seat of Original

Skin. Some people grant inexplicable value or judgment

on saturation levels of either melanin or anthocyanin,

but once the skin is flayed, the insides are remarkably similar.

It’s good to know some things stay the same.

2.

It is November, when I am twenty-four. Wendy

and I are in college. We met in a class

whose name I can’t remember, but it was

taught by a history professor who hated history

texts, a history professor with a secret life

as a literature professor, using classic novels

to teach us 20th century history, including,

naturally, Animal Farm. Predictable, but neither

of us has read it because we both went to boonie

schools low on college prep, lower in academic

opportunities (though both schools were athletically

supported well—resources neither of us desired or used).

3.

Of the books I’d been assigned in high school, I remember

three: A Tale of Two Cities, Splinter of the Mind’s Eye,

and The Metamorphosis, one for each year (my tenth grade

English teacher, on the brink of retirement and bitter exhaustion,

agreed to leave us alone if we extended him the same courtesy).

From the first of these three books, I learned

the rich exploit the poor (Okay, I already knew

that, so, really: nothing). From the second, I learned

Vader, Luke, and Leia were more interesting onscreen

than on the page (Okay, loving that far away, long ago

place, I’d read the novelization, so I already knew that,

too). And from the third, I learned that you might find

yourself transformed and exposed one day, inexplicably,

and that others will still find you undesirable, maybe even

more than you’d felt before (Okay, I’d already gone from

the small Rez elementary school to the giant white middle

school, so yeah, I already knew that last one too).

I wonder what the tenth grade book might have had

to offer, if we’d been assigned one: another lesson

already learned or another new way to understand

your place in the world you lived in? Sometimes, it’s

easier when you at least know people think you’re a

“monstrous vermin” that should be left unspeakable

and unspeaking, clicking and hissing away in your

bed, desperate for those in your life

to understand the ideas you’re trying to reach them with.

4.

Wendy and I walk across quads, a couple

hours before our evening class starts. The only

light is a strip of burnt orange clouds, a median

dividing the darkened highway of land and sky.

Dusk often finds us here together, for this hour.

The air is cold enough to make our breath visible,

ectoplasm ghosts, but we know what awaits us

on the western edge of campus. Our destination

is an exhaust vent the approximate square footage

of the small precarious, drafty houses we were raised in.

We don’t know where the warm air is being

pushed from, perhaps every heater and every

furnace of every building and every class

room and every dorm room and every lab

and every meeting room and every office

and every space claimed by others, but for

the hour of Monday sunsets before the snow

falls, this particular warmth is ours, alone.

No one can see us, when we climb the half wall

into the obscured vent, and stretch out, lie

suspended across the grate, our belongings

secured in backpacks so we don’t lose

anything to muddy sooty shadows and air

shafts into the school’s physical plant.

We come here when we long for food we

can’t articulate. Mostly we are silent

because this roaring heat joyously blasting

on us drowns out our voices unless we shout.

We watch the horizon disappear and stars try

to penetrate Buffalo’s dense light pollution and

denser regular pollution until we can’t stand the cold

air dropping on us from November’s crystalline

sky beyond the limited powers of our HVAC deity.

5.

Sometimes, we play a game, telling secrets no

one else knows, each assured the other can

not hear anything beyond hissed consonants

and mumbled vowels. (Though of course I know

I can hear hers and of course she knows she can

hear mine, and maybe even some other students

walking anonymously near us, hear these disembodied

confessions float by them, allowing us our privacy.)

We know the danger of this game, having both

made the mistake of playing a similar game with

our other friends, in which you tell three terrible

stories about yourself, but two of them are lies.

Your friends have to figure out the true one.

It’s like that Meat Loaf song, but when you think

of that title, “Two Out of Three Ain’t Bad,”

what you really mean to say here, is:

“One of These Three Is Awful.”

You can only play this game with people

who really love you, or people you are

never, not ever, going to see again, people

who maybe don’t even know your name.

6.

This activity is all fun and games until you tell them

* **** *** *** ** * ***** ** ********

and then they will never, not ever, see you

the same again, because after that they know

*** *** *** *** *** **** *** *** ** *

***** ** ********* and they know what

a crafty façade you’ve rendered, to be allowed

in their presence. You’re lucky Wendy has her own

sequence of asterisks. She recognizes that no one

who has ever heard them can unlearn them

and she knows more than most what it is like

to rise up and unflinchingly be exposed.

7.

She is sometimes a model for Life Drawing

students, and I ask her how she can stand

before twenty strangers with all of her clothes

off, knowing they will not only be staring at her

for three hours straight, but also memorizing her

body’s contours, mapping different shaded parts,

the scarred parts, the perfect parts, on sheets

of smudgy paper they will take with them

forever, maybe later, in seclusion, doing

things she does not desire for her image.

When we have this conversation, I’ve been

painting for years, but all of my models

are invented from vapor as transient as

our ghost breath on these cold November

nights. She says she knows, noting that

the breasts I draw are like none that have ever

existed on any real woman in human history.

8.

Before we graduate, she hands me a gift, a nude

photo of her taken by our friend Nate for his

photo studio class. He made only three copies

before destroying the negative. Her payment

for modeling was print number 3/3. By this time,

I’ve been writing a lot about reservation life,

and being in love and my partner Larry, who is not

the right age, or the right class or the right race or

the right gender. She says that, between the two

of us, I am by far engaging in the riskier act. She

says that when she takes off her clothes for artists

and viewers, it’s just skin she exposes, the body’s

first defense, as she makes her contribution to the art

world. At the end of the three hour session, she

can put her clothes back on and leave the scene.

9.

A month later, I understand one part of her

observation. Our friend Nate, who took

the photograph, has a painting commission

but needs a nude male reference with a small waist

and broad shoulders and, desperate, asks me

to trade sessions. If I model for him now, he will

later reveal himself and pose for me when I need it.

I have never done this but our friendship has

endured for years and I’ve recently come to see

the usefulness of life drawing, the value of truth.

His studio is an illegal space he and three

other painters rent above a machine shop.

While his studio mates leave, and sparks fly

and acetylene torch trails fill the air below us,

I fully disrobe and stand frozen, as instructed:

arms outstretched, neck extended, looking

at the network of wires and pipes crossing

his ceiling. I take very few breaks as it is

tough to get back into position after relaxing,

and frankly, it never feels normal to make small

talk, even with a friend, while you are naked.

Maintaining the pose, I discover Wendy has told me

the truth. I forget after a while that I am standing

wholly naked in the sun, as someone stares at me for

long periods, sometimes stepping close enough for me

to feel exhaled breath, inches away, to capture a contour,

the play of light and shadow on muscle, bone, and hair.

I study an enormous pair of metal eagle wings hanging

in the corner, like one of Bruce Wayne’s or Leonardo

da Vinci’s experiments. Nate has welded and riveted

them together from cut sheets of brass, individual

feathers layered and fastened in place. He tells me

the commission is for a life-sized naked angel, half

painting/half sculpture. When he finishes capturing me

on this sheet of plywood, he will cut my body loose, reinforce

my backing, and mount my wings. He says I will hang

suspended in a cathedral ceiling entryway, featured in

my own spotlight at the mansion of some wealthy Buffalo

man, presumably, until he grows bored of my body,

exposed in all its major scars, and minor perfections.

I tell Nate I’m not sure how I feel about that future,

and he says it’s a little too late for modesty, and I can

tell by the region of plywood he’s working, that he is

capturing my equipment in oil paint, linseed medium,

and brush strokes, and he promises to make me look good,

to put me in a flattering light, even as I express my reluctance.

10.

Two weeks later, Nate is gone, having used

his commission to support a move to the west

coast, and I have never seen him again, clothed

or naked, and I have never seen the finished work.

Somewhere, in some fancy foyer in Buffalo,

floats a young wooden Indian man, made of pressed

ply, layer upon layer, thinner than I am now, harboring

considerably fewer scars. He wears the wrong arrangement

of eagle feathers, for a young Indian man. I try not to think

often about this person I used to resemble. Sometimes

years pass before I’m again reminded of the way Nate talked

me into being exposed and captured and the way he then skipped

town, ducking on his promise to take the same risk for me.

11.

Wendy’s words rise more and more often, the secrets

we told each other buried in the roar of heat we could

never get enough of. She hangs on my wall to this day

in that photo Nate had titled “Lot’s Wife.” My family notices

the nude woman, in stark black and white exposure on emulsion,

in the middle of an abandoned factory, only they don’t perceive her

as nude. To them, she is naaaay-kid and it is against the way we live

to ask about such a thing, and instead, they silently honor my choices.

Wendy is right about the risks of writing, and as I have

this thought, I recall that at the end of The Metamorphosis,

the transformed “monstrous vermin” dies because his family

can no longer repress their repulsion. His father lodges

a piece of fruit deep into his back, where he can not reach,

and he gives up, owning the infection and starvation together

until he withers away and is quietly swept out of the house.

The rotting betrayal wedged into his back is an apple.

12.

The skin’s outer layer is supposed to protect the body from

outside violations, but every guard has limits. Has my likeness,

suspended somewhere in a Buffalo neighborhood I could never

afford to live in, fared any better? Does he like his role, as frozen

heavenly figure from some other culture’s beliefs, Gabriel or Icarus?

I hope at least, that this younger me faces westward so he can see

the occasional sunset and, through Buffalo’s light pollution and

pollution pollution, some constellations, a few stories made of stars,

floating in sequence against the universe’s unknown blackness.

His skin has maybe faded and chipped, and become weathered

and scarred like my own, from a botched surgery and the indignities

I’ve accrued as my years on this Earth slide and stretch into decades.

Or maybe he has protected himself better than I have.

Maybe, his arms outstretched, he has never done what

I am doing here, he has never revealed * **** *** ***

** * ***** ** ******** and he keeps his secrets,

knowing that one thing I never learned, despite being

told by multiple people over and over again.

You can only play this game with people who really

love you, or people you are never, not ever, going

to see again, people who maybe don’t even know your name.

Even then, these people must not ever know you

really can’t fly, they can’t be told the wings are weights,

when you leap off the cliff, and they can’t know that

after the fall, you’ll be left with everything irretrievably

exposed. Even if you are careful, someone may raise

a knife-sharp curiosity, break the tender membrane,

tinted with melanin or anthocyanin. Despite your best

efforts to be tough, impermeable and impenetrable,

in the end, they will successfully peel this skin.

It is good to know some things stay the same.

__________________________________

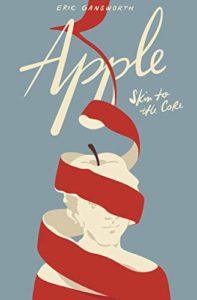

From Apple: (Skin to the Core) by Eric Gansworth. Used with the permission of Levine Querido. Copyright © 2020 by Eric Gansworth.

Eric Gansworth

Eric Gansworth, Sˑha-weñ na-saeˀ, (Eel Clan) is an enrolled Onondaga writer and visual artist, raised at the Tuscarora Nation. Lowery Writer-in-Residence at Canisius College, his books include Extra Indians (American Book Award), Mending Skins(PEN Oakland Award), and Apple (Skin to the Core), Longlisted for the National Book Award, and included in Time Magazine’s 10 Best YA and Children’s Books for 2020, and NPR’s Book Concierge. Portrait by Dellas.