Paul Newman on the “Lusty Time” He Had Filming The Long, Hot Summer with Joanne Woodward

“For us, the promise of everything was there from the beginning.”

By the time I began preproduction for The Long, Hot Summer near Baton Rouge in 1957, my divorce settlement was essentially finalized. That allowed Joanne and me to openly be together. But since the story of my marital split wouldn’t hit the newspapers for some months, and since the press—in those days, at least—didn’t just appear everywhere you went, we were able to avoid any frenzy.

It had been over four years ago that Joanne and I met backstage at Picnic; that we would finally get to work together again in Long, Hot Summer meant everything. The picture was loosely based on a William Faulkner story; I played the rakish drifter who goes to work for a rich, powerful family despot (played by Orson Welles). There’s real chemistry between my drifter and Welles’s daughter, played by Joanne. I know people have written that this was the first picture where I displayed sexiness—but if that was so, I attribute it completely to filming with Joanne. Before then, my sexuality was never there.

For the first time, Joanne and I could do what we longed for years to do in public, as well as put on the screen what had already been discovered between us. There was a glue that held us together then, and through the rest of our life together. And that glue was this: anything seemed possible. The good, the bad, and the wonderful. With all other people, some things were possible, but not everything. For us, the promise of everything was there from the beginning.

Making that movie was a lusty time together for us. The picture was hard work, a long schedule and shot on location in very hot weather because it was the end of Louisiana’s summertime. But on Saturday nights, Joanne and I would drive to New Orleans and stroll into the French Quarter and we were really comfortable. It was a cornucopia of discovery. I was wide-eyed, because I’d never really been anywhere besides New York, Boston, and LA. She introduced me to the world of antiques and antique stores; we even bought ourselves a brass bed down there.

And a dog, too. Early one Sunday morning, we were walking through the Quarter and heard all this yapping in back of us. We turned around and there was this tiny little dog behind us being held by a length of yarn in some guy’s hand. He was about the size of my fist.

“Good lord, what is that?” we asked.

“It’s a chihuahua.”

“Well, he’s a fierce little bugger,” I said.

“I raise ’em,” the guy said.

“Is this little fellow for sale?”

He nodded yes, and I bought him for sixty dollars.

The guy handed me the dog and said, “You’ll be able to keep him in your pocket for the rest of his life.”

Needless to say, that dog grew up to be the size of a small truck. We called him El Toro.

El Toro was in reality some kind of mongrel, but I adored him. He was a cheeky dog. One of the most endearing things about him was the oft-repeated story of how he never liked my onetime business partner John Foreman. Whenever John came by my house, El Toro would just slink out of the room. And one time, John happened to leave his hat on the bed and El Toro took a crap in it.

There was a glue that held us together then, and through the rest of our life together. And that glue was this: anything seemed possible. The good, the bad, and the wonderful.What also made the shoot memorable was Orson Welles’s presence. He was pretty standoffish and he seemed to feel uneasy around Actors Studio people; besides me, there was also our director, Marty Ritt (with whom I also later made Hombre, Paris Blues, The Outrage, Hemingway’s Adventures of a Young Man, and Hud) and Tony Franciosa.

Orson couldn’t understand screen generosity, where one actor allows another player in his scene to deservedly get the best camera shots. Screen generosity was not part of Orson’s vocabulary. After a number of retakes on a scene he did with me, Orson asked Marty if he could have a private word with him. They stepped away together, and seemed to be discussing something rather serious. When they came back, we did another take, and afterwards, I asked Marty what was going on.

“Orson thought you were submarining him,” he said; it was an actor’s way of saying someone was stealing his screen time.

Orson had actually been dragging his part of the scene so I’d get less screen time than he would. At the Actors Studio, we believed that what the camera should create is a sense of community among a cast. When Ritt shot the big scene where Franciosa’s character crazily keeps digging for a nonexistent buried treasure beside Welles’s barn, Tony did it wonderfully; he was powerful, organic, and unpredictable. Orson went over to Marty afterwards and wearily said, “My God, I feel old, like I’ve been riding a tricycle in a barrel of molasses.”

After the movie came out and was a big success, Marty became known in Hollywood as “the man who tamed Orson Welles.” True or not, I know Marty helped me during rehearsals. He’d make me get rid of any extraneous shit in my performance. He’d make sure to give you a line, an intention, an active verb, to use in your moment.

Marty was very good with actors, gracious and gentle. He knew that what worked best for the actor was likely what also worked best for the character. He would flare his nostrils, make noises, and ask, “Well, what do you think, kid?” or “Isn’t that funny?” Remarkable, too, is that Marty, who was once an all-state football tackle and a heavier guy, was the most graceful person on two feet. He clowned; he was whimsical; he’d do a fake waltz with some imaginary lady. He was like Zero Mostel—he could tiptoe across a floor and hardly cause a breeze.

The problem for me with a man like Marty, and especially later in my career with John Huston, was I thought I had to behave in a certain way to please them. So whatever I presented was artificial, because it wasn’t really a response from my core. And that continues till today, because I’m still not sure about what my core really is. I am no good around people with power. Even as I think of it now, my hands start to perspire.

_____________________________________

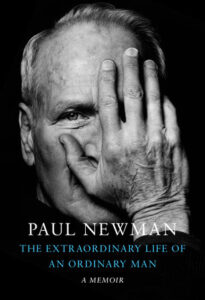

Excerpted from The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man by Paul Newman. Copyright © 2022. Available from Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.