Paul Lafargue on the Spectacle of Victor Hugo’s Funeral

“The most magnificent funeral of the century.”

On June 1, 1885, Paris celebrated the most magnificent funeral of the century: it interred Victor Hugo, il poeta sovrano. For ten days running, every newspaper laid out the public opinions of France and Europe. Paris—momentarily distracted by the red-flag procession and the onslaughts of the police in Père Lachaise, which brought back memories of the Bloody Week—returned its attention to “the most illustrious representative of the human conscience.”

The papers did not have enough room in their three pages (the fourth being taken up by advertisements) to exalt “the genius in whom the human idea lived.” The moment the language Victor Hugo had enriched with so many laudatory turns of phrase was called upon to convey the journalists’ admiration for “the hugest thinker of the universe,” however, it seemed to fail them, and they soon resorted to images. The front page of one evening edition, lost for words, printed a picture of the sun sinking into the ocean. Hugo’s death was the death of a star. “Art is over!”

The nation, stirred up by journalistic enthusiasm, threw three hundred thousand men, women, and children behind the pauper’s carriage that conveyed the poet to the Pantheon, and a million more onto the squares, streets, and sidewalks along the route.

A black shroud veiled the Arc de Triomphe’s imperial glory; the light of gas lamps and electric streetlamps filtered lugubriously through the crêpe. There were crowns made of flowers and crowns made of plush, portraits of Hugo on his deathbed, bronze medallions engraved with the words: National mourning . . . In short, all the symbols of desperate grief were requisitioned, and yet the huge crowd had no regrets about the death of the man, and no memories of the poet. Hugo was irrelevant to them. They appeared not to realize that the person being brought to the Pantheon was “the greatest poet who had ever lived.”

The boisterous and convivial crowd loudly expressed their satisfaction with the weather and the parade. They asked about the names of the celebrities and the delegations from the different cities and countries filing past for their pleasure. They admired the monumental bouquets fitted on the roofs of the carriages. They applauded the rifle clubs’ fife players whose discordant songs agonized their ears. They greeted Déroulède and his green-frocked solemnity with ironic laughter. And to put the finishing touches to their happiness, there was the blazon of the Benni-bouffe-toujours bringing up the rear with a sautéed rabbit and their heraldic arm—a colossal cardboard baster.

Both the actors and spectators were on top of the world. It is true that the inhabitants of the grand boulevards, disappointed that the corpse wasn’t being paraded past their doors, speculated bitterly about the tidy sums they might have pocketed. Sick at heart, they told each other how windows and balconies could have been rented out for hundreds or thousands of francs—how in three turns of the clock they might have made more than twice the next six months’ rent.

But the sourpusses’ displeasure was drowned out by the general rejoicing. The brasseries à femmes on the Boulevard Saint-Michel spilled out in heaps on the sidewalk; it cost an arm and a leg to be baked in the sun while you wet your lips with adulterated beer. Common folk, who had claimed the good spots at dawn with a chair or a table, a bench or a ladder, rented them out to the curious in exchange for two days of fun and easy living. Greedy hoteliers, cabaret owners, and odd-jobbers smiled gleefully as they fished in their pockets, fingering the five-franc coins the festivities yielded. One of them said, with great intensity, “A Victor Hugo would have to die every week to keep business up!”

And business was indeed booming! The business of flowers and mortuary emblems; the business of newspapers, lithographs, and bronze, gold, and silver zinc lyres, electrotype medallions, and pictures mounted on pins; the business of black crêpe and armbands, scarves, and tricolor and multicolor ribbons; the business of beer, wine, and smoked meat (the hungry people were eating and drinking, standing in the street in front of counters wherever they happened to be and whatever the price); and the business of love—provincials and foreigners, come from the four corners of the earth, were honoring the dead by feasting in horizontal positions.

The funeral services of the first of June were worthy of the dead man being led to the Pantheon and worthy of the class who escorted the corpse.

Neither French nor foreign revolutionary socialist organizations, which are the conscious party of the proletariat, sent representatives to Victor Hugo’s funeral. The anarchists made an exception and, to distinguish themselves yet again from the revolutionary socialists, sought to raise their black flag among the multicolored flags of the cortege. Elisée Reclus, their notable man, begged his friend Nadar to inscribe his name in the mortuary register. However, the government forbade the unfurling of the red flag: Monsieur Vacquerie said that, in exile, Hugo had always walked behind the red flag, every time one of the victims of the coup d’état was lowered into the ground.

The radical press demanded the right to carry the flag of the Commune through the streets, recalling that in 1871 the outcast of the Empire had opened his house in Brussels to the vanquished of Paris. Everyone seemed to want to invite the revolutionaries to gather around Victor Hugo’s coffin, as if it were the rallying point of all republican parties. But the revolutionary socialists refused to take part in the carnivalesque pageant of June 1.

The City of London, though invited, did not send a delegation to the poet’s funeral. Members of its council claimed they hadn’t been able to make head or tail of his work. To explain their refusal in this way was indeed a gross misunderstanding of Victor Hugo. There is no doubt that the honorable Michelin, Ruel, and Lyon Allemand of London imagined the writer who had just died was one of those proletarians of the pen who rent out the brains of the Hachettes of the editoriat and the Villemessants of the press with weekly or yearly leases.

But if they’d only been told that the dead man kept his account at Rothschild; that he was the largest shareholder in the Bank of Belgium; that, being a farsighted man, he had stashed his money outside of France, where revolutions were raging and there was talk of the general ledger being burned; and that he only threw caution to the wind and paid five million to help liberate his homeland because the investment would turn a profit; if they had only known that the poet had amassed five million by peddling sentences and words; that he’d been a clever literary dealmaker, a master in the art of haggling and drawing up contracts in his favor; that he’d gotten rich by ruining his publishers (a thing that had never happened before); if they’d been familiar with the dead man’s credentials, certainly the honorable representatives of the City of London, the commercial heart of both worlds, wouldn’t have traded their attendance at this important ceremony for anything. On the contrary, they would have insisted on honoring the millionaire so adept at wedding poetry with double-entry bookkeeping.

The French bourgeoisie, better informed, saw in Victor Hugo one of the most perfect and brilliant personifications of their own instincts, passions, and thoughts.

The bourgeois press, intoxicated by the hyperbolic praise it was heaping in thick columns upon the decedent, neglected to emphasize the representative side of Victor Hugo, which will perhaps be his most meaningful credential in the eyes of posterity.

I am going to try to rectify this omission.

__________________________________

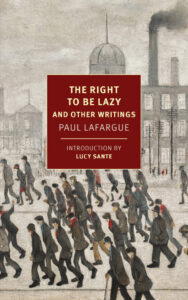

Excerpted from The Right to Be Lazy: And Other Writings by Paul Lafargue, translated by Alex Andriesse.

Paul Lafargue

Paul Lafargue (1842–1911) was born in Santiago, Cuba, and lived there until the age of nine, when his family returned to their hometown of Bordeaux, France. In his early twenties, Lafargue began studying medicine in Paris, but after participating in a socialist gathering was barred from the French university system and left the country to continue his studies in London. There, he served as Karl Marx’s secretary and married Marx’s daughter Laura. Moving back to France in 1870, he participated in the Paris Commune and was again forced to flee the country, first to Spain and then to England. After amnesty was granted to the Communards in 1882, he and Laura returned permanently to France, where Lafargue gained notoriety as a writer of pamphlets and articles on politics and literature, founded the country’s first Marxist labor party, and earned his law degree. On the night of November 26, 1911, he committed “rational suicide” with Laura at their home near Paris. Lenin spoke at their funeral.