Nobody—and I mean NOBODY—warned me about my pubic hair.

It glistened for years, springy and sprite, an Ivory Soap-scented welcome mat for lucky episodic visitors. I never gave it much thought, certainly didn’t see a need to clock in every day, just to make sure it was—what, still spry and bouncy and squeaky clean? It wasn’t until a chance glance in the full-length divulged its devotion to downfall. My shimmering triangle had dimmed and turned a flat slate gray threaded with an occasional whimper of silver I now think of as “last light.”

The strands grew thin, thinner and desperate. They disengaged and drifted, leaving behind a patchy landscape that looked like the fallout from a tender war. I keep up with the upkeep of what is now mostly bald skin, but I can’t help but think it’s like spritzing

So ladies, take this from a wise, much older woman—your beloved patch will go gossamer, then go gone. Nothing can be done. Weaves seem silly. I offer thoughts and prayers.

Aging, and its accompanying theater, resides rent-free in my head nowadays.

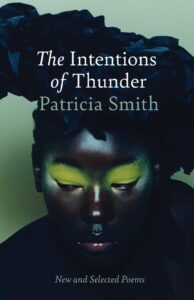

Aging, and its accompanying theater, resides rent-free in my head nowadays. I was recently charged with the unenviable task of culling poems from years upon years of my life in order to convince myself and everyone else that they rose from a single throat. My fat little edition of new and selected enters the world at the end of September. Constructing it was like watching that film everyone says you see just before you die, but you don’t die. There’s no therapy like clawing back through both your triumphant and dismal decades and reliving them stanza by stanza, line by line, iamb by iamb. Residing so intently in my yesterdays also brought me face-to-face with a teeny inevitable detail I’ve been dodging and weaving and watusi-ing to avoid.

Somehow I have turned 70 years old.

Now I always check that last sad box when I’m asked my age on forms. I have quietly become a ma’am. I belong to the generation without a letter. I mourn things like pubic hair and the ability to move without ouching.

I have also learned that while I am old, I am by no means ordinary. I’ve been a poet for most of my life, and poets have a much different relationship to the passing of days. Seeing the world the way we do—through the widened gaze of witnessing—is like being plugged directly into a coursing current. So much happens to us and because of us. We don’t age until we do.

My odd little poet biography began on the west side (best side!) of Chicago at the foot of my father Otis Douglas Smith—raconteur of Washington Boulevard, griot of the ghetto, a raucously animated storyteller who never allowed me to let the world sit still. He made everything breathe—even the trees outside our tenement windows had names. (And attitudes when they were pushed askew by Chitown’s fabled Hawk. Delilah was particularly shady. She spat the first goddamn I ever heard.)

I was an expert on a life I hadn’t yet lived, and I wanted everybody to hear about it.

Every dawn was a blank canvas that Daddy would fill with real-life characters and their concerns—the folks he worked with at Leaf Brands Candy Company, for instance, were stars in an endless soap opera with an installment every night after dinner. By the time I actually met them, I knew so much of their business that I couldn’t meet their eyes. They were walking free verse.

To this day, I focus on an empty seat at every reading I do and thank my father for helping me see a world that my bored Chicago public school teachers could never conceive of. The first and only time poetry was mentioned in middle school, we opened the book, Robert Frost did something in the woods—I remember it was snowing—and we were done.

My first true attempts at poetry were self-guided, painfully rhymed, drenched in abstractions and exhausted platitudes. They were so important. I sprouted boobs and well-meaning drivel at the same time.

I see it in my students and I remember it in myself. Those fresh lines of poetic revelation all began the same way—“I need” or “I see” or “I think” or “I want” or “I feel” or “I believe” or “I love.” I, I, I. I was an expert on a life I hadn’t yet lived, and I wanted everybody to hear about it. But I hadn’t yet had my heart smashed by a thoughtless crush, been called a nigger (OK, at least not loud enough for me to hear), lost my father to a gunshot, been publicly dissected and humiliated, seen an impossibly young Prince open for Rick James, shaded a Supreme Court justice or exchanged actual words with thee Gwendolyn Brooks.

All hail to the poetry slam, which schooled me in the art of living a flawed, slapdash life out loud for everyone to see. Wow and wow-wee. The heyday of the slam was my rock ’n’ roll era. I was skinny denim and leather and big voice and boy cologne. I was knock-knee and shudder. The slam was my fever, my teacher, my critic, my glow, my shadow. It was way too much and never enough. If I had to choose the most important stage of my life, it would be those Sunday nights in a long neon-washed room, scribbling a new one just before taking the stage to spit it, loving or hating my scores, getting better, drinking more than I should, becoming part of a community that felt plugged directly into an electrical socket. Time waited for us to write it. We were ageless, and so, so sexy.

But there came a moment when I caught a smeary glimpse of myself in that mirror behind the bar (you know the one) and realized the fun couldn’t last forever. Our little literary bubble was just that. We were coddled rebels, reciting our poems from memory, delivering lines like they were gospel, mixing in beats and film, impressing the hell out of Dan Rather, showing up infuriated or deflated with fresh poems about something that happened in the world an hour ago.

And the happening didn’t stop. My father was murdered. Young Black men in the backs of patrol cars blew their heads open while their hands were cuffed. OJ lived to screw up again. Rodney King’s face was smashed to a dark liquid. Dahmer feasted on our sons and brothers. We thought Oklahoma City was the worst that would ever happen. One tower fell, then its twin. My father died. My father died. My father.

Poetry isn’t a recreational activity. It is a calling out, a beckoning near, a circle of arms. It’s our connection to each other.

Enamored with persona poems, I wrote one in the voice of an undertaker who lamented the mounting losses of young people to gun violence. My undertaker talked about how to fit the puzzle pieces of a face together so the mother could see her son again, one last time, almost the way he was. The first time I did the poem in public, at a public housing meeting, a woman got up and fled the room.

She had lost her son, and now she pictured him on the slab while the undertaker worked from a Polaroid to veer him back toward breath.

I realized then that we write not for audiences but for other human beings, real people, people who can’t get the right words to fall in place like we can, people who are convinced that they are utterly alone, that the awful thing that is happening to them has never happened to anyone else. Poetry isn’t a recreational activity. It is a calling out, a beckoning near, a circle of arms. It’s our connection to each other.

My poetry began as a father’s sly growl, became a spectacle on a rickety stage washed in limelight, and now is a 70-year-old woman’s walk back into a thousand yesterdays. But it was always the dead son, the grieving mother, unleashed laughter, brutal witnessing, storm pummeling flower. We lean into each other on a ceaseless search for lyric strong enough to end one day and begin another. Look at the poem we’ve been writing all this time. Look how we keep revising the last line.

__________________________________

The Intentions of Thunder by Patricia Smith is available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon and Schuster.

Patricia Smith

Patricia Smith is the author of eight books of poetry, including Incendiary Art, winner of the 2018 Kingsley Tufts Award for Poetry, the 2017 LA Times Book Prize, the 2018 NAACP Image Award and finalist for the 2018 Pulitzer Prize; Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah, winner of the Lenore Marshall Prize from the Academy of American Poets; Blood Dazzler, a National Book Award finalist; and Gotta Go, Gotta Flow, a collaboration ion with award-winning Chicago photographer Michael Abramson. Her other books include the poetry volumes Teahouse of the Almighty, Close to Death, Big Towns Big Talk, Life According to Motown; the children's book Janna and the Kings and the history Africans in America, a companion book to the award-winning PBS series. Her work has appeared in Poetry, The Paris Review, The Baffler, The Washington Post, The New York Times, Tin House and in Best American Poetry and Best American Essays. Her contribution to the crime fiction anthology Staten Island Noir won the Robert L. Fish Award from the Mystery Writers of America for the best debut story of the year and was featured in the anthology Best American Mystery Stories.

Smith has collaborated with the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra, Angela’s Pulse Dance Troupe, the Sage String Quartet and singer Meshell Ndegeocello; “Blood Dazzler,” a dance/theater production based on her 2008 book, sold out a two-week run at the Harlem Stage under the guidance of award-winning director Patricia McGregor; her one-woman show “Life After Motown,” produced by Nobel Prize winner Derek Walcott, was performed in residency at the Trinidad Theater Workshop.

Smith is a Guggenheim fellow, finalist for the Neustadt Prize, a National Endowment for the Arts grant recipient, a two-time winner of the Pushcart Prize, a former fellow at Civitella Ranieri, Yaddo and MacDowell, and a four-time individual champion of the National Poetry Slam, the most successful poet in the competition’s history. She is a distinguished professor at the College of Staten Island and in the MFA program at Sierra Nevada College, as well as an instructor for Cave Canem and the Vermont College of Fine Arts Post-Graduate Writing Program.