Hold-up in the Rue Ordener by Colette

There’s something going on over there . . . Farther off, beyond the crowd of people who have been prevented from moving forward by a barrier of police and Paris guards; they spread in unequal streams over both sides of the road like long stagnant black pools . . . Behind the thick silica dust flying around like spume on waves . . . There’s something going on over there, on the right side of the street, something everyone is looking at and nobody can see . . .

I’ve just arrived. In order to get to the front I’ve used brute force, like a woman at the sales in a department store, combined with the soft blandishments of the weaker sex: ‘Monsieur, please let me through . . . Oh, I can’t breathe, Monsieur . . . You are so lucky to be tall like that . . .’ They let me go to the front because in this throng there are hardly any women. I touch the blue-uniformed shoulders of a policeman—one of the pillars of the crush barrier—and I try to move forward a little more:

‘Monsieur l’agent . . .’

‘You can’t go through!’

‘But those people running over there, look, you’ve let them through.’

‘Those men are journalists. And anyway they are men. Even if you were from the press everybody in a skirt must stay quietly over here.’

‘Perhaps Madame would like my trousers?’ a voice from the faubourgs suggests.

Everyone laughs loudly. I bite my tongue. I look at the street barricaded with intermittent whirlwinds. I am focusing, like everybody, on an almost invisible point behind the dust and the curtain of trees: a grey shack of a building with its roof at an angle . . . I jig around, in agitated curiosity:

‘What’s going on? What have they done about it? Where are they?’

The policeman, his eyes in the street, doesn’t answer. My neighbour, a woman with a lot of hair and protecting a child with each arm, looks me up and down. I turn on the charm:

‘Tell me, Madame, are they over there?’

‘The robbers? Oh yes, Madame. In that house over there.’

Her tone is clearly: ‘Where have you sprung from? Everybody knows that!’ A large fellow at my back coolly informs me:

‘They are inside. The police are afraid they might escape so they are going to blow them up . . .’

‘Blow them up? Oh, my word! I’ll bet a tenner they get away and leave Lépine high and dry.’

This sporting remark comes from a pale blasé young man who can’t keep still: shiftily he presses against the people around him, pushes against me as if by accident. I wager that he’ll put his head down at the first opportunity, dive under the arms of the policeman and sprint up the empty street . . .

They are over there . . . They are going to be blown up . . . The dreadful mindset of the curious onlooker takes hold of me, the same which makes women go to bullfights, boxing matches and even to the foot of the guillotine, that spirit of curiosity which so perfectly makes up for a want of true courage . . . I dance around, bend my head to protect myself from the clouds of dust . . .

‘Madame, if you think it’s easy to see anything standing next to someone as fidgety as you!’

It’s the mother, the stern woman by my side. I mutter something at her and she says tartly:

‘But it’s true! What’s the point of me being here since nine this morning just so you get in front of me at the last moment? If people save a place, they save a place. And anyway, if you have a great hat like that, you take it off!’

She bossily holds out for her place in the front row and seeks—gets—general approbation. Behind me I hear a chorus of ‘Take your hat off!’, jokes which date from last year’s vaudeville, but which leave a funny taste in the mouth when you remember what’s going on over there . . .

All of a sudden the wind throws at us, with the dust that crunches between our teeth, the familiar smell, that distinctive smell of burning: over there it’s no longer the dust which is blinding the street but the greyish blue of a smoke churned up by the wind . . . The shouts behind me rise like flames:

‘They’re there! They’re there! Can you hear? I heard a shot! The house has been blown up! No, it’s gunshots! They’re getting away! They’re getting away! . . .’

Nobody has seen or heard a thing, but this excitable crowd pressing on me from every side is inventing, without realizing it, perhaps telepathically, all the goings-on over there. Pressure has built up and now, irresistible, a surge breaks through the barrier and carries me forward. I am running so that I won’t be crushed; I run with my neighbour and her two agile children. The sporty, blasé young man shoves me aside with his shoulder, a thousand are coming along behind. We run, with a noise like a herd of animals, towards the goal, ever more invisible: over there.

There is a sudden halt, then people run back, half knocking me down. On my knees I hang on to two solid arms which at first shake me hard and then pull me up. I haven’t time to say thank you.

‘Where are they? Where are they?’

A rather puny working woman in a black apron gasps:

‘They’ve gone! They’ve escaped! Everybody’s after them!’

She can’t possibly know, she’s seen nothing. She shouts, she’s telling everyone what she has imagined. The throng drags us both along and lifts us up. I take shelter for a moment against a very tall man who lets himself be jostled and shaken without turning a hair, his two arms lifted and holding up a camera which he is blindly and incessantly pointing . . .

The dust, the smoke are suffocating . . . While the wind shifts the cloud covering us, I realize I am very near the building collapsing noisily in flames. But all at once the crowd carries me away and I am struggling not to be crushed . . . Confused cries; the voices are hoarse and throaty like sobbing. A shout is heard clearly, spreads and gives some coherence to all this uproar: ‘Kill them! Kill them!’ I can breathe again, thanks to a gap in the crowd . . .

‘Kill them, kill them!’

And once more I am pushed, bruised, shoved up against the back of a motor car that is being opened to heave up into it something heavy, long and inert . . .

None of those shouting near me and around me can make out what is happening. But they are shouting because it’s contagious, imitating others, almost, I might say, because they think it’s the right thing to do.

That fair-haired quarryman yaps, mechanically, staring straight ahead. ‘Kill them!’ shouts a plump southerner in a guttural voice, and from his tone you would think he was saying: ‘Exactly!’ or crying ‘Encore!’ at a café-concert. I stare in amazement at two shopgirls, arm in arm and as jolly as at the Foire de Neuilly, who let themselves be pushed and shoved and jostled along and only stop shrieking ‘Kill them!’ to burst into giggles . . .

Between the heads, between the moving shoulders, I can see the ruined building with flames licking up around it. A man leans out of a smashed window and throws a mattress on the ground, the sheets soaked in so much blood, pink in the midday sun, that it seems to me artificial.

‘Kill them!’

The violence and fury of the shouting is increasing! I feel the motor car slowly shudder and begin to move. I must once again run if I don’t want to fall under the feet of people following it. As it drives off it seems to draw the whole crowd along with it like a magnet.

Finally I can slow down and stop. The automobile and its screaming escort vanish into the distance like a black stormcloud. Already the white road to the centre of Paris is covered by a yelling multitude, still half ignorant of what was in the midst of them. Breaking away from the main body of the crowd, I remain for some time looking at the cluster of flames fed by the dried wood, magnificent, joyous, shifting in the wind. So that’s where they had gone to ground . . .

Just a speck in the crowd, oppressed and blinded only a little while ago, I begin to see clearly again. It’s my turn to go off into Paris and find out what dramatic event I have just witnessed.

2 May 1912

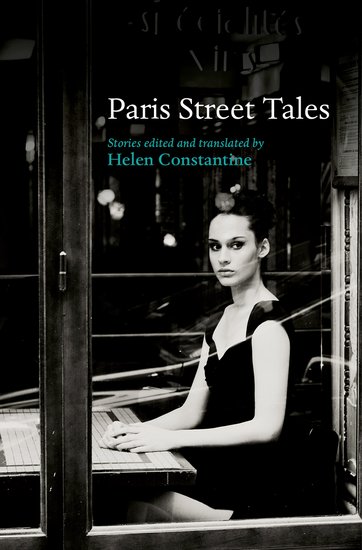

From PARIS STREET TALES. Used with permission of Oxford University Press. Copyright © 2016 edited by Helen Constantine.