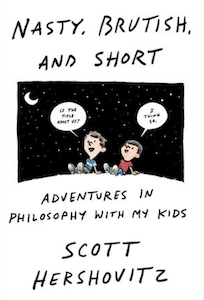

Parenting 101: Does “Because I Said So” Ever Really Work?

Scott Hershovitz on Figuring Out Power and Authority with Kids

“You are not the boss of me,” Rex said.

“Yes, I am.”

“No, you’re not.”

“Fuck you.”

That’s it. That’s the whole story. Except I didn’t say “Fuck you.” Except in my head. And my dreams. Because nothing is more frustrating than a kid who won’t put on his shoes when it’s time to leave the house.

“Put on your shoes.”

Silence.

“Put on your shoes.”

Maddening silence.

“Rex, you need shoes.”

“No shoes.”

“Rex, you have to wear shoes. Put them on.”

“No shoes.”

“Put on your shoes.”

“Why?”

Because they protect your feet. Because they keep you clean. Because the whole world has a sign that says no shoes, no service. But also: Because I said so.

“No shoes.”

“Fine. We’ll put them on when we get there.”

When did this conversation happen? I don’t know. When didn’t it happen?

Rex learned you’re not the boss of me in preschool. He was three or four. But he’d lived you’re not the boss of me for longer than that. It’s the creed of little kids.

They may do what you say. But only when it suits them.

*

Was I the boss of Rex? That depends on what it means to be the boss of someone.

I did boss Rex around, in the sense that I told him what to do. But as the story suggests, I didn’t have much success.

Philosophers draw a distinction between power and authority. Power is the ability to bend the world to your will—to make the world be the way you want it to be. You have power over a person when you can make him do what you want him to do.

And I had power over Rex. In a pinch, I could simply put the shoes on him. And I did. But I had other ways of getting my way. I could withhold what Rex wanted until he did as I said. Or give him a reward. Or persuade him. (Not really.) Or better yet, trick him. (A well-placed whatever you do, don’t put on your shoes was, for a long time, the fastest way to get them on his feet.)

Rex learned you’re not the boss of me in preschool. He was three or four. But he’d lived you’re not the boss of me for longer than that. It’s the creed of little kids.

Rex also had power over me. Indeed, if you were keeping score, it would be hard to say which one of us had more success bending the other to his will. Rex couldn’t push me around. But he could throw himself on the floor, go boneless, or just generally resist until he got his way. He could also be cute in a calculated effort to control me. That often worked. And there’s a lesson here: even in the most asymmetrical relationships, power is rarely one-sided.

But authority typically is. To differing degrees, Rex and I had power over each other. But only I had authority over him. What’s authority? It’s a kind of power. But it’s not power over a person, at least not directly. Rather, authority is power over a person’s rights and responsibilities. You have authority over another person when you can obligate him to do something simply by commanding him to do it. That doesn’t mean that he will do it. People don’t always do what they are obligated to do. But it does mean that he’ll have breached his duty if he doesn’t.

When I tell Rex to put on his shoes or, more recently, wash the dishes, I’m making it his responsibility to do so. Until I tell him to do the dishes, it’s not his job to wash them. It would be awesome if he did! But I’m not in a position to get mad if he doesn’t. Once I’ve told him to wash the dishes, that script flips. It’s no longer awesome if he washes them; it’s what’s expected. And I’ll be angry if he doesn’t do it.

Philosophers illustrate the difference between power and authority with a stickup. You’re walking down the street when a guy with a gun demands all your money. Does he have power over you? For sure, you’re gonna cough up the cash. Does he have authority? No. You weren’t obligated to give him money before he demanded it, and you’re not obligated to give it to him now. In fact, you’d be within your rights to tell him to get lost (though I wouldn’t recommend it).

Contrast the stickup with the tax bill that comes each year. The government also demands money. And it’ll put you in prison if it doesn’t get what it wants. So it has power. Does it have authority? Well, it certainly says it does. In the government’s view, you are obligated to pay your taxes. Are you actually obligated? In a democracy, many people would say yes—you’re obligated to pay what the government says you owe.

But not Robert Paul Wolff. He didn’t think the government could obligate you to do anything. Indeed, he doubted that anyone could obligate you to do anything simply by saying that you had to do it.

Over the course of his career (which started in the 1960s), Wolff taught at Harvard, Chicago, Columbia, and UMass—an impressive set of institutions for an avowed anarchist. That’s because Wolff isn’t the sort of anarchist who takes to the street seeking mischief and mayhem. (At least, I don’t think he is.) Instead, Wolff is a philosophical anarchist, which is just a fancy way of saying he’s skeptical about all claims to authority.

Why? Wolff argues that our ability to reason makes us responsible for what we do. More than that, Wolff says, we’re obligated to take responsibility for what we do, by thinking it through. According to Wolff, a responsible person aims to act autonomously—according to decisions that she makes, as a result of her own deliberations. She won’t think herself free to do whatever she wants; she’ll recognize that she has responsibilities to others. But she insists that she, and she alone, is the judge of those responsibilities.

Wolff argues that autonomy and authority are incompatible. To be autonomous, you have to make your own decisions, not defer to someone else’s. But deference is just what authority demands.

It may be okay, Wolff says, to do what someone else tells you to do. But you should never do it just because you were told to do it. You should do it only if you think it the right thing to do.

*

Wolff’s conclusion is more radical than it might seem. He’s not just saying that you should think before you follow an authority’s orders. He’s saying that those orders don’t make a difference—that no one can require you to do something simply by saying you should do it—not the police, not your parents, not your coach, not your boss, not anybody.*

*At least, if you’re an adult. Kids, Wolff says, have responsibility in proportion to their capacity to reason.

That’s surprising. And it didn’t take long before philosophers spotted problems with Wolff’s argument. The leading critic was a character named Joseph Raz, who was, for a long time, the Professor of the Philosophy of Law at Oxford.

And there’s a lesson here: even in the most asymmetrical relationships, power is rarely one-sided.

Raz argued that Wolff had missed something important about the way that reasons work. Sometimes when you think about what you should do, you discover that you have reason to defer to someone else—reason to do as they direct, rather than decide on your own.

To see what Raz means, suppose that you’d like to learn to bake, so you sign up for a class. Your instructor is a whiz-bang baker. And now she’s barking orders. Measure this, mix that. Knead the dough. Not that much. Should you do as she directs?

Wolff would have you second-guess every order. Each time, he’d have you ask: Is this really what I should do? But how could you possibly answer that question? You don’t know anything about baking. That’s why you’re in the class! Your cluelessness gives you a good reason to do as you’re told.

And: You don’t lose your autonomy when you do. Sure, you’ll be doing as someone else directs. But only because you decided that you ought to defer to her judgement. Of course, if you do that too often, your autonomy will be compromised. But deferring on occasion—when you judge it the right thing to do—is consistent with governing yourself.

*

My father is endlessly amused by the ways in which Rex and Hank challenge my authority, since he sees it as comeuppance.

My mother had a strong dictatorial streak. She liked to lay down the law. And I did not like to follow it. We were locked in combat from the time I was little.

She’d issue an order, and I’d immediately want to know: “Why?”

“Because I said so,” she’d say.

“That is not a reason,” I’d insist. I was a four-year-old philosophical anarchist.

“That’s all the reason you’re going to get,” she’d say. And she was stubborn. So she was right.

Whenever I looked to my father for help, he’d say, “Just make your mother happy,” a sentence I found every bit as infuriating as because I said so.

“Why are we living under the tyranny of this woman?” I would wonder. Well, not at four. But certainly by 14.

Now I’m the one who says because I said so.

I don’t like to say it. And it’s rarely my first move. I like to explain what I’m thinking when the boys ask why. But there isn’t always time. And I’m not always up for a full conversation—in part because they relitigate issues endlessly.

But also: Even if I explain myself, they might not see the issue my way. And that’s fine. They can attempt to persuade me. Sometimes they succeed. But if they fail, my view wins out. Which means that because I said so is often the final reason I offer, even if it’s not the first.

__________________________________

Excerpted from NASTY, BRUTISH, AND SHORT: Adventures in Philosophy with My Kids by Scott Hershovitz, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Scott Hershovitz

Scott Hershovitz

Scott Hershovitz is director of the Law and Ethics Program and professor of law and philosophy at the University of Michigan. He holds a BA in philosophy and politics from the University of Georgia, a JD from Yale Law School, and a D.Phil. from the University of Oxford, where he was a Rhodes Scholar. Professor Hershovitz served as a law clerk for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg of the U.S. Supreme Court. He is married to Julie Kaplan, a social worker, whom he met at summer camp. They live in Ann Arbor with their two children, Rex and Hank. His book is Nasty, Brutish, and Short. Photo by Rex and Hank Hershovitz.