A billionaire pays me to offset his carbon. He jets around the world while I do very little. Breach of contract includes:

• Watching TV

• Looking at the internet

• Driving a car

• Using a phone

So mostly I just sit at home and read. Which is fine. That’s what I used to do anyway, before our partnership began, back when I was what statisticians would call a discouraged worker. Now I am encouraged! We have a good library system in town. I walk to the nearest branch, check out a stack of books, come home to my apartment and read. I eat raw food. My personal footprint is minimal.

A camera mounted in a taxidermied hawk watches the corner where I read. I wear a wristband that keeps me honest when I’m outside the apartment. I’m not supposed to ride in anything that burns fossil fuels. If I accelerate suspiciously, the gyroscope in my wristband will know, and then my billionaire will know. The wristband also measures my heart rate, skin conductance, and receptivity to new ideas. It’s powered by the movements of my hand as I turn the pages of library books. That’s called piezoelectric energy. Technology these days, I swear. If you think about it, it’s practically a miracle.

My niece Clara wants to know what I do for a living. Clara is 7. Every Sunday evening I eat dinner with my sister and niece. I walk to their place.

It’s an hour-long walk. When my billionaire brought me on board as his carbon-offset partner, I had to go vegan. It’s amazing: I dropped 30 pounds! But I guess my sister feels sorry for me, because when I come over she always cooks an extravagant meal. Or anyway, it’s extravagant for me, in that it’s cooked. Roast beef with scalloped potatoes. Roast chicken with artichokes. Roast anything. Cooked anything. Does that put me in breach? As long as someone else does the cooking, I don’t think so. Or maybe I am in breach, I don’t know—the contract I signed was pretty dense, and I’m no lawyer. I’m sure I’ll be notified if my behavior is out of line.

My niece is at an age, though. She no longer wants to know why the sky is blue, or why ponies are smaller than horses. Now she just wants to get into the nitty-gritty. For instance, “What’s your job, Uncle Chester?” All adults have jobs. Firemen. Dentists. Presidents of the United States. How can I explain my weird gig to a 7-year-old?

“I get paid to do nothing,” I tell Clara. “Or as little as possible.”

“Why?”

“Because the environment is teetering on the brink. So people are on the lookout for innovative solutions. Some of us do nothing so a few of us can do almost anything. Almost everything. The net carbon output is neutral, and the world as a whole benefits. The trees, the whales, the billionaires—everyone wins!”

It’s nice that my billionaire calls me. He’s not contractually obligated to, but he does it anyway.

My billionaire likes to talk at me through the taxidermied hawk, which has a speaker installed in its beak.

“Lion hunting in Zimbabwe. That was on the bucket list, for sure. Finally snorkeled the Great Barrier Reef—too late. The whole place was bleached!”

“Oh, yeah, I read about that.”

“Time really is short. You hear about this baobab die-off? They’re dying off and no one knows why. I just got back from Africa, but I guess I have to go right back. Gotta see these baobabs before they’re gone.”

“That’s amazing,” I say. “I’ve always wanted to see a baobab.”

“Yeah? I never even heard about them till last week! Really wanna experience them now, though, while I still can. Schedule’s pretty tight, but I had my people make room. We ended up pushing back the Wailing Wall to next month. The Wailing Wall can wait, right? The Wailing Wall ain’t going anywhere!”

The hawk sits on a glazed branch on my mantel. It fits with my decor. My apartment is old and even has a fireplace, though it was filled in a long time ago. I’ve lined the mantel with my handsomest hardcovers and rare first editions. The hawk serves as a bookend. It’s a small, angry-looking creature with dark arches over its eyes and a sharply hooked beak, which is where the billionaire’s voice streams out.

“Anyway, gotta run—I’m meeting Elon for a jet-pack lesson!”

“Wow. So cool.”

“Ciao!”

It’s nice that my billionaire calls me. He’s not contractually obligated to, but he does it anyway. Talk about down-to-earth! I feel privileged to know someone like him, and it’s an honor to be kept in the loop. Some billionaires lock themselves away in their mansions, but mine makes a point of rubbing elbows with people of a lower station. I really respect him for that. It humanizes wealth, makes it seem concrete and attainable. Which is important in a meritocracy. That way the have-nots know their striving isn’t in vain.

“Meritocracy?” Clara says.

“That’s the kind of system we live in,” I say, between forkfuls of lasagna. “Your value-add determines your reward. What that ultimately means is that—almost by magic—society structures itself in the fairest possible way. The cognitive elite rise to the top. As they should.”

“I just hope you’re getting enough protein,” my sister says.

“With a billionaire as conscientious as mine, you bet I am. He’s outfitted my whole apartment with smart furniture, to help me organize and optimize my low-carbon lifestyle. My smart fridge knows when I’m running low on antioxidants and automatically orders more. My smart toilet analyzes my waste to make sure all my glucose levels and whatnot are normal. The toilet is actually a scientific marvel. It scans my microbiome and archives the results in a massive anonymized data set. So every day, just by performing my natural bodily functions, I contribute to the store of human knowledge and progress in general.

“Did you know,” I ask my sister, “that recent studies have shown a strong correlation between gut fauna and key entrepreneurial indicators? You know, risk tolerance, leadership pheromones, extrasensory consumer trend perception, stuff like that. Were you aware that many market influencers can see in the ultraviolet? It’s true. They’re different from us. I looked at my toilet scans, and apparently I lack the bacillus. Which explains my ambition deficit.”

This feels like a teachable moment, so I turn to Clara.

“In the past, people thought genius was a result of genetics. But these days, scientists believe it’s a by-product of certain bacteria in the digestive system. And so, if we could take the stuff in my billionaire’s guts and move it into my guts, then I could become a visionary just like him.”

My sister sets down her fork. “A fecal transplant?”

I nod as I stuff lasagna into my face.

“I don’t know him well enough to pop the question—not yet. It’s a pretty intimate ask, you know? But we’re establishing a strong rapport. It won’t be long now–”

“Are you talking about poop?” Clara says.

“Yes, Clara, poop. Well, not exactly poop, but the organisms in the poop. The fauna.”

“Chester. She’s a little young for this.”

“But this is science! Kids love science.”

“You’re going to eat someone’s poop?”

“No, Clara, I don’t eat it—I inject it up my rectum.”

“Chester.”

“What’s a rectum?”

“Honey, sometimes Uncle Chester has ideas and says things that don’t quite match up with what everyone else believes.”

I cackle and brandish my fork like a scepter.

“That’s what they said about Steve Jobs!”

__________________________________

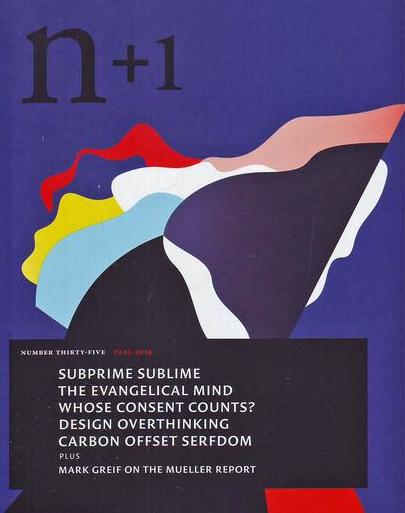

From “Parasite Air,“ a story written by Trevor Shikaze, featured in the fall 2019 issue of n+1 (Issue 35).