“Who are you?” asked the doctor.

Tony understood what the question implied. An Asian man in a torn bellhop uniform and an elderly white woman with a head wound walked into a hospital. It sounded like the beginning of a bad joke.

“I’m Miss Abadi’s doorman,” said Tony. “Is she okay?”

“She’s doing fine. Nothing’s broken, but we’re not ruling out a concussion yet.” The doctor spoke slowly, enunciating each word as though he were speaking to a toddler. Tony was used to this kind of stilted English. He’d heard it before from the residents in his building, Tammy’s teachers, recruiters from technology companies. Some did it as a polite gesture or out of self-ordained compassion. Many couldn’t hide their impatience. A few were brazenly condescending. They all did it because they assumed that it was necessary. They weren’t completely wrong. Tony was grateful for the decrease in their speech speed. It was their tone that could kill a man.

He returned to his seat in the waiting room where, the doctor had said, a police officer would meet him to take a statement. The police. Before this, his mind had been racing with thoughts of suspension or losing his job completely. The cost of a replacement uniform, the dry-cleaning bill to remove the bloodstains from his white shirt, whether Kim could apply makeup on his face to hide the bruises. The police had slipped his mind. Now it was all he could think about. They could arrest him, drag him to court, throw him in prison. His teeth clenched at a new thought: they could revoke his visa.

He had seen an episode of Judge Judy about a brawl between two men. The unassuming defendant said that he’d struck the other man with a chair to protect his girlfriend. How had Judge Judy ruled? He could almost hear her smoker’s voice now, see the glasses perched low on her nose. He scratched at the sides of his pants and snapped off a loose thread. The defendant with the face of a cherub—hadn’t she found him guilty?

Then he thought of someone who scared him more than the police and the courts: his wife. Regardless of how they sorted him, Kim was the final arbiter. With her he didn’t have high hopes for a fair trial. She had told him to walk away from trouble. And what had he done? Chased trouble down and punched it in the face.

“Eighty-two, eighty-three, eighty-four.” The bald man next to him was counting ceiling tiles. Tony looked up, squinting at the fluorescent light. He hated hospitals. This one smelled like old socks and bleach. The hallways wouldn’t shut up. Clogs squeaking on the floor, metal carts clattering. The incessant beeping of monitors. Announcements over the speaker system paging doctors to the ICU. The sounds bounced off the sterile hard surfaces, amplifying his anxiety.

Back in China, Tony had only visited the hospital a handful of times. He remembered the day his father dislocated his shoulder for skipping school. I fell, he told the nurses.

“Tony!”

Someone was calling his name.

“Tony!”

He turned around and saw Oliver Wright from apartment 505. The young man looked less imposing outside The Rosewood. His voice—thin and uneven. Strands of loose hair dangled across his forehead.

“Why are you here?” said Tony.

“To help you,” said Oliver.

“Help me?” Tony was used to being the help, not the other way around.

Oliver reached his hand out toward Tony as if to hug him, but then hesitated. “I’m so sorry,” he said. “Your face.”

Tony had caught brief reflections of himself in the ambulance window and the nurse’s metal instruments, but he hadn’t really taken stock of his injuries. He didn’t need a mirror to know that it was bad. He cradled his face in his hands, slowly touching all the lumps and bumps: the taped gauze on his cheek, stitches on his lips, thick bandage on his nose. Every jolt of pain jerked his memory. He had hit someone, but he was a victim too.

Oliver said, “What you did was really brave.”

“You saw?” Tony was hoping that Oliver could help him piece together what had happened and persuade the police that none of it was his fault.

Oliver’s words tripped over each other as he explained, “Yes, well, no, not all of it. I was on my phone. Client call. Inside the lobby. Can’t always see clearly through the revolving doors. I know they’re glass but sometimes the sunlight—it hits them in a weird way.”

“I hope I’m not in trouble,” said Tony.

“With who?”

“The police.”

“It’s just a formality,” Oliver said, eyes narrowing with confusion, before leaving to get him something to drink.

Of course Oliver didn’t get it, thought Tony. Why would he? Oliver was a US citizen, a lawyer. Tony was a thirty-four-year-old foreigner with an ugly accent and no green card. He didn’t have money or influential friends to vouch for him like he did in China. No job at a prominent university that would afford him somebody’s benefit of the doubt. The police could lock him up, or worse, deport him. It was a crime to be violent, and Tony had committed it in public.

He thought about Tammy. Kim would insist that they follow him if he were forced out of the country. He vowed to himself that he would make them stay in America without him. He would send money from China for rent and food and for all of Tammy’s lessons—piano, Kumon, swimming, dancing. Whatever it took, however long they had to be apart. He would make Kim promise to keep Tammy in line with her studies. That was most important.

“I think you drink this, right?” said Oliver, setting a Styrofoam cup on the table. “It’s green tea.”

“I’m afraid,” said Tony.

“It’ll be okay.”

“I can’t talk to the police.”

“Why?” said Oliver.

Tony stayed silent, taking in the creases in Oliver’s face. His worry lines, Tony noticed, were etched with sadness. He met the young man’s eyes, holding on until they softened, went watery at the edges. He sensed that Oliver was seeing him for the first time too.

“Let me help you,” said Oliver.

“How?”

“I’m a lawyer. This is what I do.”

“I can’t afford it.”

Oliver sipped his tea and shook his head. “I don’t let friends pay.”

Friends, thought Tony, with a happy lurch in his gut. He nodded slowly, keeping his head down so that Oliver wouldn’t notice how emotional he was getting.

He heard Kim’s voice in his head: He doesn’t mean it. Don’t be a fool. His wife didn’t have faith in people. There’s always something in it for them. Tony used to agree with her theory, but Oliver seemed different. He had come all the way from The Rosewood to the hospital. He was taking off from work. He didn’t have to do any of this for his doorman, but he was offering to help. You’re too trusting, Kim might say. But Oliver was a good man.

“So what happened here?” The police officer arrived in denim jeans and sneakers. The yellow notepad in his hand was the only indication of his authority. He had already talked to Clara, he said, and just had a few follow-up questions.

“He hit me and I protect her,” said Tony, words tumbling out before his brain could correct them. That should have been past tense. His English regressed when he got nervous. “The man kept hitting me. I only hit back because he hit me.” Tony pointed to his own bruised face as evidence. “I’m a doorman. It’s my job.”

Oliver nodded. “This is all true.”

“I have a work visa,” said Tony. “In my house. I can show you. Please. I have a daughter.”

“Whoa, man, calm down. You’re all over the place. Start from the top,” said the officer, as if rehearsing a line that he had heard on a TV cop show.

“The top?” said Tony, shrinking into himself.

Oliver put a hand on Tony’s shoulder and said, “Around noon today, a man assaulted Clara and stole her purse. He tried to run away, but Tony stopped him.”

The officer and Oliver kept talking, but Tony was barely listening anymore. He could tell from the officer’s stance—his casual slouch, the way he nodded along placidly, barely taking any notes—that he wasn’t going to be in any trouble. He was safe.

“That’s all I need,” said the officer. He turned to Tony and said, “You did a remarkable thing today. Really banged up that guy. We have a criminal off the streets because of you.”

The officer shook his hand, accidentally pulling at the stitches of his ripped flesh, but Tony was too relieved to care.

He had only talked to one police officer before today and had learned from that encounter to avoid them. On a rainy night in Flushing during his first year in America, a mob of teenagers had robbed him on his way back from the public library. He’d been there late, checking out grammar books after work. They took thirty-three dollars from him and left him on the wet ground. When the police officer arrived, he appeared irritated.

“Are you drunk?” the cop had asked. “What are you doing out this late at night?” Without waiting for answers, he said, accusingly, “Only someone up to no good would be roaming these streets right now.” He rattled off more questions that Tony couldn’t understand at the time. What he did understand was that the cop was not on his side. The cop was more dangerous than the muggers. The muggers just took his lunch money, but the cop could ruin his future.

Since that night, Tony was robbed three more times. He surrendered forty-four dollars to a masked man who put a gun to his back, twenty-eight dollars to two boys circling him on bikes, and an even thirty to a man in an empty subway car who said, “Empty your pockets, chink.” He wasn’t scared anymore. Those people were predictable. Easy to satisfy. They just wanted money, and Kim always made sure that Tony had a wad of cash on him. Mug money, she called it. It was her way of protecting him. Just give them the cash, she would insist. Don’t fight back.

Oliver nudged Tony as the doctor approached them. “You two are with Clara Abadi? Follow me,” he said.

They strolled down a long corridor. A nurse passed them, holding a bedpan. Tony peeked into an open room. A slack-faced man wearing an oxygen mask stared blankly ahead. His TV flickered silently. Across the hall, a little boy was sleeping. The series of plastic tubes going in and out of his limp body looked like thick strands spun by a spider. Hospitals had a way of making people look sicker than they really were.

In the next room sat Clara, propped up by a legion of pillows. She sported a pair of black eyes and a splint on her nose, but she was humming a show tune as she furiously scooped Jell-O into her mouth. Clara didn’t look weak. She looked battle-tested. When she saw Tony and Oliver at her door, she waved at them as if they were long-lost friends.

“How are you feeling?” said Tony.

Clara raised her spoon in the air. “Nothing like a punch to the face to start your day!”

His legs faltered at the joke. Even with a foam neck brace, bandages on her jaw, and a purpling bruise on her arm, she still managed to reach for humor.

“I know what you did for me,” said Clara. She grabbed his arm and pulled him close. Splinted-nose to splinted-nose. Tony couldn’t breathe. His lungs were too polite, too stunned. Without any of her usual bravado, she whispered, “You’re my hero.”

He didn’t know what to say. This was the same woman who haughtily walked past him every day. The same woman who treated him like a servant. Who he was pretty sure didn’t know his name. But here she was, in a hospital gown, no lipstick, scooping Jell-O, calling him a hero.

As he held Clara’s gaze, a part of him he kept wound up and tucked away began to unspool. Just then, he did something that he’d never done since he had arrived in America. It was only now, an inch away from the lips of a movie star, that Tony let himself cry.

__________________________________

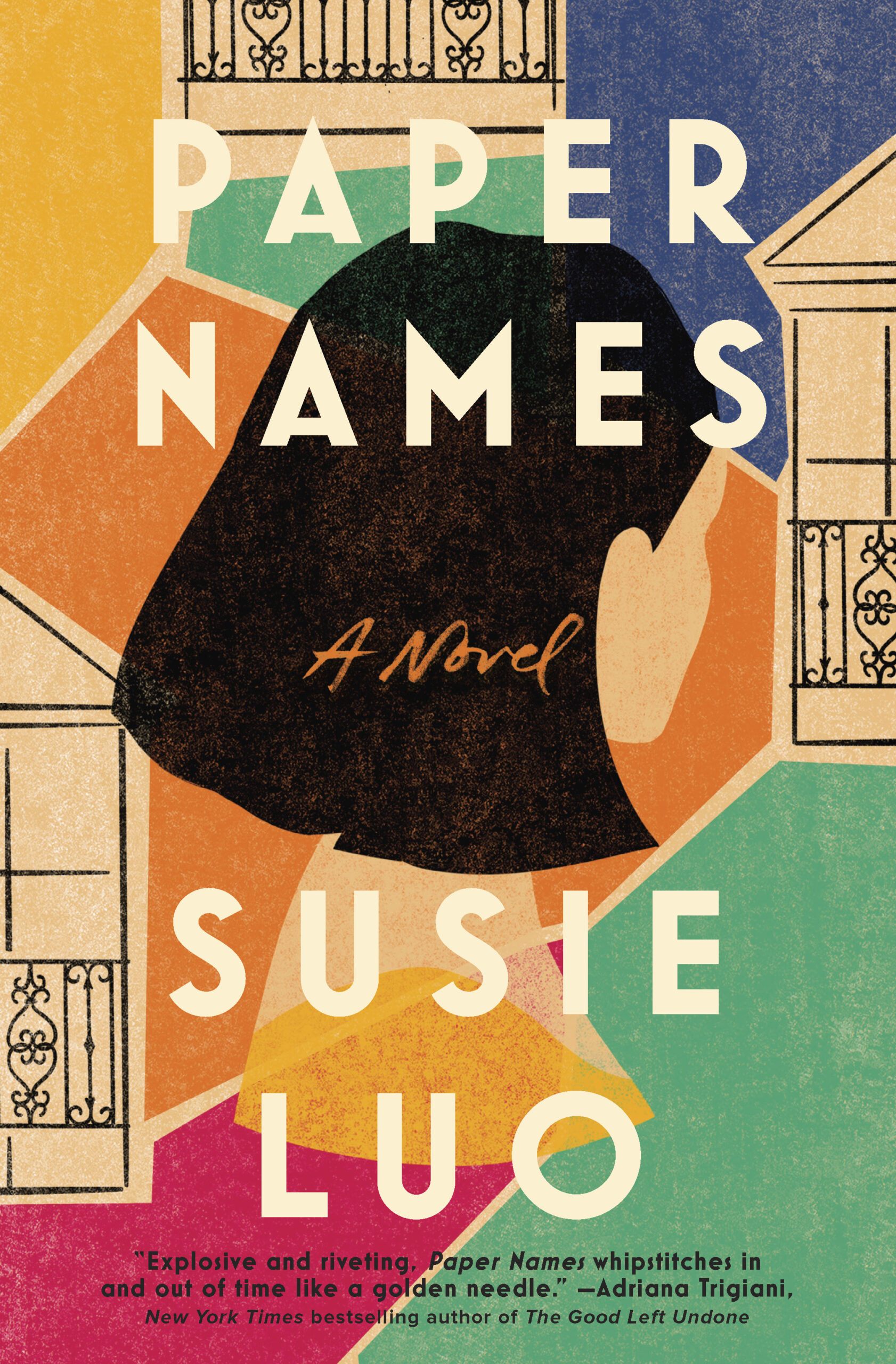

Excerpted from Paper Names by Susie Luo © 2023 by Susie Luo, used with permission from HarperCollins/Hanover Square Press.