Paula Karst appears in the stairwell, she’s going out tonight, you can tell right away, a perceptible change in speed from the moment she closed the apartment door, her breath quicker, heartbeat stronger, long dark coat open over a white shirt, boots with three-inch heels, and no purse, everything in her pockets—phone, cigarettes, cash, all of it, the set of keys that keeps the beat as she walks (quiver of a snare)—and her hair bouncing on her shoulders, the staircase that spirals around her as she hurries down the flights, swirls all the way to the lobby, where, intercepted at the last second by the huge mirror, she pulls up short, leans in to fathom her walleyed irises, smudges the too-thick eyeshadow with a forefinger, pinches her pale cheeks, and presses her lips together to flood them with red (indifferent to the hidden flirtatiousness in her face, the divergent strabismus, subtle, but always more pronounced when evening falls). Before stepping out into the street she undoes another shirt button—no scarf even though it’s January outside, winter, la bise noire, but she wants to show her skin, wants the breath of night wind against the base of her throat.

*

Among the twenty-odd students who trained at the Institut de Peinture (30 bis, rue du Métal in Brussels) between October 2007 and March 2008, three of them stayed close, shared contacts and warned each other about sketchy deals, passed along contracts, helped each other finish rush jobs, and these three—including Paula with her long black coat and smoky eyes—have a date tonight in Paris.

It was an occasion not to be missed, an exquisite planetary conjunction, as rare as the passage of Halley’s Comet!—they got all worked up online, grandiloquent, appending their messages with images pulled from astro-photography sites. And yet, by the end of the afternoon, each one was imagining the reunion with reluctance: Kate had just spent the day perched on a stepladder in a lobby on avenue Foch and would have happily stayed sprawled at home in front of an episode of Game of Thrones, eating taramosalata with her fingers; Jonas would have preferred to keep working, to get ahead on a tropical jungle fresco

he had to deliver in three days; and Paula, who had just flown in that morning from Moscow, was jet-lagged and not so sure the meeting was a good idea after all. But something stronger than them propelled them outside at nightfall—something visceral, a physical desire, the desire to recognize each other, faces and gestures, timbre of voices, ways of moving, drinking, smoking, all the things that would be reconnecting them any minute to the rue du Métal.

*

It was an occasion not to be missed, an exquisite planetary conjunction, as rare as the passage of Halley’s Comet!Bar thick with people. Clamor of a fairground and dim light of a church. They show up on time, all three, a perfect convergence. Their first movements throw them against each other, hugs, sluice gates open, and then they wend their way through the crowd single file, welded together, a unit: Kate, platinum hair with dark roots, 6’1″, thighs bulging in ski pants, motorcycle helmet in the crook of her elbow and big teeth that make her top lip look too thin; Jonas, owl eyes and grayish skin, arms like lassos, Yankees baseball cap; and Paula, who is already looking brighter. They reach a table in a corner of the room, order two beers and a Spritz—Kate: I love the color—and then immediately begin that continuous pendulum movement between the bar and the street that sets the night’s cadence for smokers, cigarettes between their lips, flames in the hollows of their hands. The day’s weariness disappears in a snap, excitement is back, the night busts open, there’s so much to talk about.

Paula Karst, fresh off the plane, you first! Tell us of your conquests, describe your exploits! Jonas strikes a match and his face flutters for a fraction of a second in the light of the flame, skin taking on a coppery glow, and in a flash Paula is back in Moscow, voice husky, back in the huge studios of Mosfilm where she spent the fall, three months, but instead of panoramic impressions and sweeping narration, instead of a chronological account, she begins by describing the details of Anna Karenina’s sitting room, which she had to finish painting by candlelight after a power failure plunged the sets into darkness the night before the very first day of filming; she begins slowly, as though her words escort the image in a simultaneous translation, as though language is what allows us to see, and makes the rooms appear, the cornices and doors, the woodwork, the shape of the wainscotting and outline of the baseboards, the delicacy of the stucco, and from there, the very particular treatment of the shadows that had to stretch out across the walls; she lists with precision the range of colors—celadon, pale blue, gold, China White—and bit by bit she gathers speed, forehead high and cheeks flaming, launching into the story of that long night of painting, that mad crunch. She describes the hyped-up producers, their black parkas and Yeezy sneakers, how they cracked the whip over the painters in a Russian full of nails and caresses, reminding them that no amount of delay would be tolerated, none, but letting them glimpse possible bonuses, and Paula suddenly understood that she would have to work all night. She was in a panic thinking about painting in the dark, convinced that the tints couldn’t possibly turn out right and that the seams between panels would be visible once they were under the lights, it was insane—she taps her temple with her index finger while Jonas and Kate listen, rapt, silent, recognizing in her a desirable madness, one they are also proud to possess—and she goes on, telling them how stunned she was to see a handful of students turn up from the École des Beaux-Arts, hired by the set decorator as backup, broke and talented, maybe, but liable to totally botch the job, and that night she was the one who prepared their palettes, kneeling on the plastic drop sheets on the floor, working by the light of an iPhone flashlight that one of them held over the tubes of colors as she mixed them in proportion, after which she assigned a section of the set to each of them and showed them which finish to use, moving from one to the next to refine a stroke, deepen a shadow, glaze a white, her movements at once precise and furtive, as though her galvanized body was carrying her instinctually toward the person who was hesitating, veering off course, and finally around midnight each one was at their spot and painting in silence, concentrating, the atmosphere of the set stretched tight as a trampoline, coiled, unreal, faces in motion lit by candlelight, eyes gleaming, pupils jet black; all you could hear was the rasp of brushes against the wood panels, the whisper of the soles of shoes against drop sheets, and breathing of all sorts, including that of a torpid dog curled up in the middle of it all and then a voice burst out from who knows where, an exclamation—Бля, смотри, смотри, как здесь красиво! Look, would you look at that! It’s fucking beautiful!—and if you listened closely, you could hear the beat of a Russian rap song playing softly; the studio hummed, filled with pure human presence, and the tension was palpable until dawn. Paula worked tirelessly—the deeper into the night, the more her movements were loose, free, sure; and then around six in the morning the electricians made their entrance, solemn, bringing the generators they’d gone to fetch downtown, some one shouted Fiat lux! in a tenor voice and everything was lit up again—powerful bulbs projected a very white light on the set and Anna Karenina’s grand sitting room appeared in the silvered light of a winter morning: there it was, it existed; the high windows were covered with frost and the street with snow, but inside it was warm, cozy, a majestic flame crackling in the hearth and the scent of coffee floating through the room; the producers were back now, too, showered, shaved, all smiles—they opened bottles of vodka and cardboard boxes containing piles of warm blini sprinkled with cinnamon and cardamom, handed out cash to the students, grabbed them by the scruff of the neck with the virile connivance of mafia godfathers or yelled English words into voicemail boxes that vibrated in Los Angeles, London, or Berlin; the pressure fell but the fever didn’t pass just yet, each of them looked around and blinked, dazzled by the thousands of photons that now formed the texture of the air, astonished by what they had accomplished, more than a little dazed; Paula turned toward the tricky seams, worried, but no, it was okay, the colors were good, and then there were shouts, high-fives, hugs, and a few tears of exhaustion, some fell to the ground with their arms flung wide while others did a dance step, Paula kissed one of the extras for a little longer than necessary (the one with the dark eyes and strong build), slipped a hand under his sweater onto his searing hot skin, lingered in his mouth while phones started to ring again, everyone gathering their things, doing up their coats, wrapping scarves around their necks, pulling on gloves or taking out a cigarette; the world outside fired up again, but somewhere on this planet, in one of the large Mosfilm studios, they were waiting for Anna, now, Anna of the gray eyes, Anna who was madly in love, yes, it was all ready, cinema could arrive now, with life along for the ride.

__________________________________

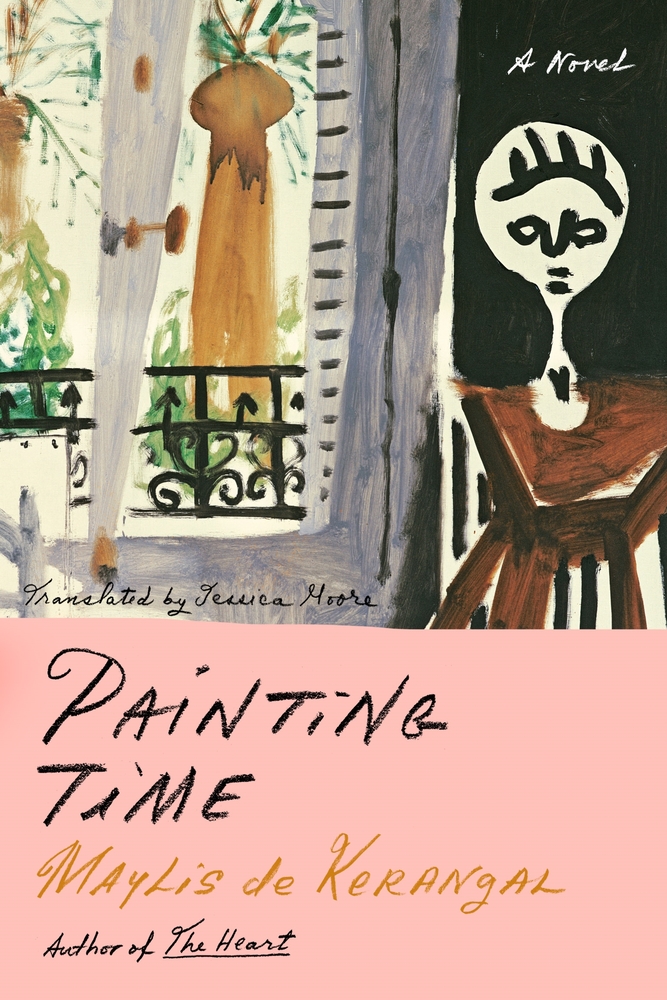

Excerpted from Painting Time: A Novel by Maylis de Kerangal. Translated from the French by Jessica Moore. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, April 20, 2021 Copyright © 2018 by Éditions Gallimard. Translation copyright © 2021 by Jessica Moore. All rights reserved.