Painting Outside the Lines: On the Life and Work of Abstract Artist Emily Mason

“Her best works—across mediums—came from ceding control, allowing herself to become a ‘conduit’ for the unknown.”

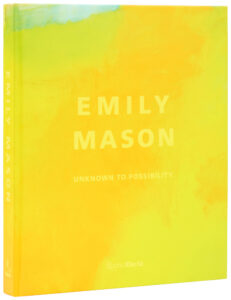

Emily Mason knew the importance of documenting a life, specifically an artist’s life. The first time I met her was when we were putting together a monograph on her mother, the abstract artist Alice Trumbull Mason. “This book was conceived as a tribute to my mother’s life and a testament to the perseverance of her inner core,” Mason wrote in the foreword. She died in December 2019, five months before the book on her mother was published. At times, it feels like Mason simultaneously laid the foundation for how to make a book on her, one that ideally feels like an extension of the artist, even in her absence.

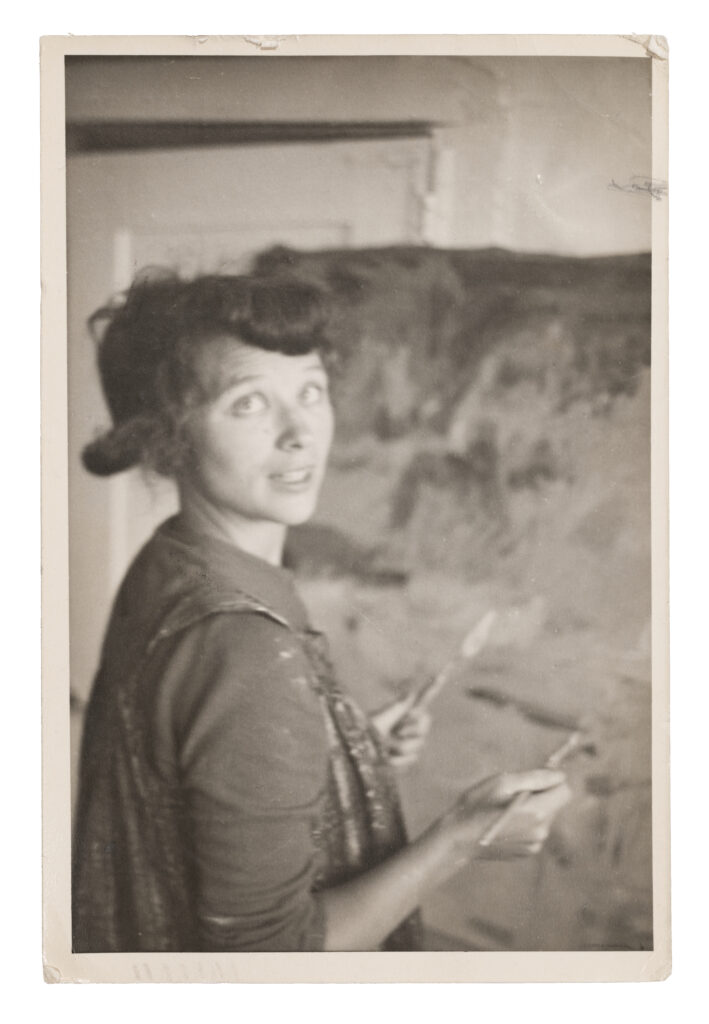

Born in 1932 in Manhattan, Mason was very much a product of the New York art scene. She grew up painting in her mother’s uptown studio and absorbing the conversations and ideas of her mother’s friends and fellow artists: Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Josef Albers, Ray Johnson, to name a few. Like Alice Trumbull Mason, Emily Mason chose to make abstract art, though of a very different kind—whereas her mother made carefully planned geometric paintings, Mason’s paintings were intuitive washes of color. This artistic lineage made an impression on Mason in so many ways, but what strikes me is her inherited drive to pursue her vision regardless of its reception at the time. In other words, she was committed to her work.

Sapphire Pool, Emily Mason.

Sapphire Pool, Emily Mason.

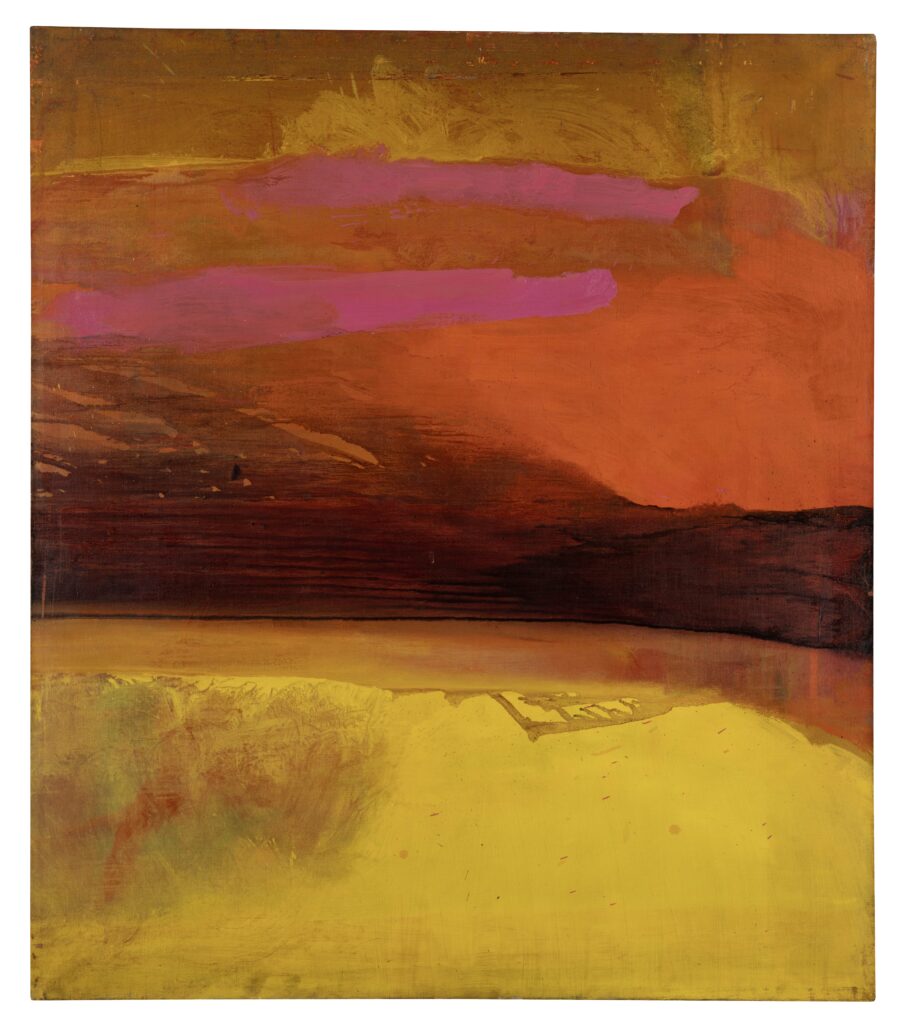

As Barbara Stehle observes in her nothing less than groundbreaking essay for this book, there were some downsides to Mason growing up among such big personality–artists—she had to figure out how to carve her way. Steadfast, Mason developed her own artistic language early, one rooted in her approach to color. She mixed her oil paints directly on the canvas and refrained from using white or black to alter her colors. Each artwork evolved into a brilliant patchwork, the result of “a series of moves, like a chess game,” as Mason put it.

Outshine the Moon, Emily Mason.

Outshine the Moon, Emily Mason.

The turning point for Mason happened at the age of twenty, when she spent a summer at the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Maine. She often referenced the pivotal day when Jack Lenor Larsen, the founder of the school, hung colorful skeins of wool and illustrated how one color could inflect and transform another simply by being side by side. The fact that Mason traced the seeds of her vision to a lesson in craft is no coincidence—she treated paint as a material, in the same way she would treat yarn. “It is not an exaggeration to say that Emily Mason is one of the few American painters fully bound up in the early pedagogical life of the studio craft movement during the 1950s and 1960s,” Jenni Sorkin writes in her enclosed essay. Sorkin lays out how Mason’s relationship to craft set her apart not only from her mother’s lineage but also from her own contemporaries.

It feels like Mason simultaneously laid the foundation for how to make a book on her, one that ideally feels like an extension of the artist, even in her absence.

Like more artists than the historical record is inclined to admit, Mason did not neatly belong to an art movement—and she was resentful when asked to choose one, which often meant choosing Abstract Expressionism. The art critic David Ebony, who was close with Mason and produced the first book on her art in 2006, says he spoke about this often with the artist—how she “didn’t really fit into” any category, and how she “was very much content with that.”

Equal Paradise, Emily Mason.

Equal Paradise, Emily Mason.

This is one of many special anecdotes that Ebony shares in a roundtable conversation published in Emily Mason: Unknown to Possibility with artists Nari Ward (a former student of Mason’s), Carrie Moyer, and Steven Rose, who is also the director of the Emily Mason and Alice Trumbull Mason Foundation. Over the course of this lively exchange, we hear them reflect on Mason’s legacy and reminisce on what she was like as a person, colleague, and teacher—she became an important fixture at Hunter College, where she taught for over thirty years, and was known for inspiring her students to experiment. “[She] awakened something in me to this notion of inventing my own approach rather than thinking about what’s the right way to do something,” Ward says.

Emily Mason, Martha’s Vineyard, 1959.

Emily Mason, Martha’s Vineyard, 1959.

One of Mason’s richest outlets for experimentation was actually in her prints, layering colors that held the same transparent quality of her oils. “They’re like painting cubed,” Moyer observes. And indeed, Mason saw her prints as “printed paintings,” on the same plane as her oils. Like many other artists, she didn’t compartmentalize her mediums; paintings, prints, and oils on paper were all in conversation with one another. The plates section in the monograph emphasizes this in beautiful, resonant pairings chosen by Steven Rose.

Emily Mason in her Chelsea Studio, 2016. Used with permission of Steven Rose.

Emily Mason in her Chelsea Studio, 2016. Used with permission of Steven Rose.

As with her paintings, Mason delighted in the somewhat unpredictable nature of making prints—how she could never fully know what the image would look like after going through the press. For Mason, her best works—across mediums—came from ceding control, allowing herself to become a “conduit” for the unknown. In her essay, Stehle convincingly argues that out of all the people Mason encountered in the New York scene in her youth, John Cage was one of the most influential, specifically his saying “get your mind out of the way,” which became a kind of mantra for her. “Mason, like Cage, cultivated the art of letting go,” Stehle writes. It is in this spirit that we arrived at the subtitle of this book: “Unknown to Possibility,” the title of a 2012 yellow painting that Mason pulled from a poem by Emily Dickinson, her namesake:

What I can do—I will—

Though it be little as a Daffodil—

That I cannot—must be

Unknown to possibility—

This verse distills much of Mason’s art and person: open, humble, enmeshed with nature. For while she remained in New York all her life, she also spent the summers of her last fifty years in Brattleboro, Vermont. Her studio was a repurposed chicken coop, the wide doors always open to the trees. “It was as if she painted in nature,” Stehle writes. “Its proximity infused her work.”

Emily Mason, Vermont, 2018.

Emily Mason, Vermont, 2018.

“Why isn’t she more famous?” critic Jackson Arn asks of Mason in a 2024 piece in the New Yorker, praising her as “one of the most ravishing post-New York School abstract painters,” as well as “the most underrated.” When I read these opening sentences of Arn’s piece, I couldn’t help but think of what has also been said of Alice Trumbull Mason. “I’ll be famous when I’m dead,” the artist herself used to say. Both faced hurdles as women artists, as well as artists choosing unpopular forms of abstraction in their day. And while Mason and her husband had a rich relationship of creative exchange, his career ultimately took precedence over hers. It is a sad pattern to see these monographs only published after the artists’ deaths. But while we can’t change the past, we can influence the future by continuing to tell their stories, by documenting their remarkable lives as they desired and deserved.

__________________________________

Elisa Wouk Almino

Elisa Wouk Almino is a writer, editor, and literary translator based in Los Angeles. She is currently the editor-in-chief of Image, the style and culture magazine at the Los Angeles Times. She is the editor of Emily Mason: Unknown to Possibility, publishing with Rizzoli this fall.