Painting Emotion: How Claude Monet Turned His Inner Life Into Art

Jackie Wullschläger on the Creative Philosophy and Practice of the French Impressionist Master

During the overcast summer of 1879, in the riverside village of Vétheuil halfway between Paris and Rouen, a restless painter paced his garden, waiting for an hour’s sunshine. When the cloud lifted, he slipped through his gate bordering the Seine, made rapid sketches of the water and the reflections of its grassy islets, and returned home fast to be at his sick wife’s bedside. Camille “had been, and still was, very dear to me,” Monet said, but he was falling in love with someone else.

Alice, hot-tempered, highly strung and married to one of Monet’s collectors, was close by. Bankruptcy had lost this once gilded couple their paintings, their Paris apartment and their country chateau, and they were sharing the Monets’ cramped terraced house. While devotedly nursing Camille, Alice became fascinated by Monet.

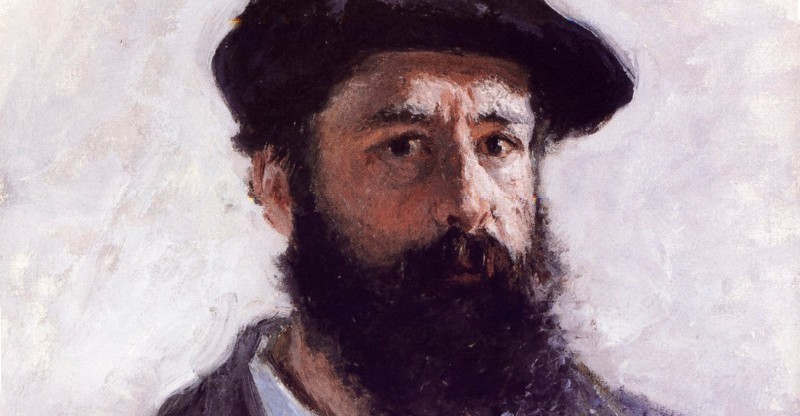

Camille died on 5 September and Alice described her last day. “The poor woman suffered horribly, it was a long and terrible agony, and she remained conscious until the last minute. It was heartbreaking to see her say her sad goodbyes to her children.” Alice did not allow herself to relate what happened next. Monet seized a canvas and sketched his dead wife. “I found my eyes fixed on the tragic countenance, mechanically trying to seek the sequence, the degradation of the colours that death had just imposed on the motionless face. Shades of blue, yellow, grey, and I don’t know what… My automatic instinct was first to tremble at the shock of the colour.”

Only a man of tremendous self-belief could hold his nerve while transforming his private, fleeting impressions…into defining, iconic images.

But Camille Monet on Her Deathbed is about far more than the play of colors: the quick, coarse bluish-violet-white marks veiling the pallid face unfold Monet’s blizzard of grief. A torrent of slashing horizontal strokes rushes along the lower part of the canvas, as if submerging and carrying away the body. It is a portrait of Camille disappearing.

Monet had made his reputation painting Camille. She features in fifty pictures, strolling in gardens, relaxing on a river embankment, windswept on the beach—images forever connecting Impressionism with everyday happiness. But after her death, he hardly depicted a figure again. In a winter that came early in 1879, he went back to the Seine and, a hot-water bottle in each pocket to warm his hands, stood on its now frozen surface, painting frost, ice floes, snow-covered fields lit by a pale sun: nature transformed, on a gigantic scale, into a shroud of mourning. Monet was thirty-nine, almost halfway through his life, and at its turning point.

In Vétheuil he developed a fresh way of working—to trap the same scene at different seasons, hours, to paint time passing. “Monet is only an eye, but what an eye,” was Cézanne’s famous, deprecating praise. It has distorted interpretation of Monet ever since. Cézanne admired his friend’s unerring, nuanced vision, rapture at the visible, directness in translating that delight into pictorial fact, but he defanged him into emotional neutrality and implied an intellectual void. Giving primacy to what was seen, to the shimmering surfaces of his canvases, the remark underplays the roles in Monet’s painting of feeling, thought and memory.

This book attempts to tell Monet’s life as he felt it: his joys and sorrows, loves and disappointments, what he read, his connections to cultural currents, and how all this, and especially his closest relationships, inspired his choices of what and how to paint.

Three times, Monet’s art changed decisively when the woman sharing his life changed. To excavate the unrecognized contributions and the voices of Camille Doncieux, Alice Raingo and Blanche Hoschedé, the special atmosphere with which each surrounded him, the extent to which they curated the milieu of his paintings, is not to diminish the force of Monet’s originality, but to rethink how he worked, and how his paintings work on us, to enlarge “only an eye” to admit heart, soul and mind.

Monet himself talked little of these things. “Monet the Taciturn” is the title of Thadée Natanson’s affectionate memoir. Natanson’s Monet was a “raptor” with a devouring gaze who sat silent, as in a trance, in his wide-brimmed straw hat, watching his water lilies. If he opened his mouth, it was to puff on a Caporal cigarette, from which “scrolls of smoke climbed and renewed themselves around him.” Vanishing into his garden, into his paintings, Monet, one of the most popular artists of all time, became what Degas aspired to be: illustrious and unknown.

Discretion and reserve were elements of his character. A decade after becoming Alice’s lover, Monet was still writing to her as “chère Madame” and using the formal “vous” pronoun. His adored younger son could not bring himself to address his father by the familiar “tu.” And Monet never painted a nude, the only great artist from the Renaissance to the early twentieth century not to do so.

Yet his paintings are the opposite of restrained. They embrace sensual experience, and are built on what Meyer Schapiro called “the fury of the brush.” His letters reveal his voracious appetite, for art and life: “I work in the rain, in the wind. I gorge myself on it”; “I have a terrible thirst to be near you.” He is always hungry, always greedy, “j’ai grand faim”; “I will spoil myself like the big mouth I am.” Painting both answered an emotional need—“it was a joy for me to see this furious sea, it was like a nervousness”—and drove introspection—“I plunge back into examining my canvases, that is to say, continuing my tortures. Oh, if Flaubert had been a painter, what would he have written?”

Impressionism, with its breezy brilliance at fixing the artist’s sensation, inevitably led towards interiority: to painting suggesting mutability, memory; to brushstrokes eloquent for their own sake rather than strictly representational; eventually to forms of abstraction. Monet made the full journey in a single lifetime—the sole Impressionist to push the movement’s implications through to the end. He began rendering broad, busy scenes and people, steamships in port, crowds on the boulevards—the sociable existence shared with Camille in the 1860s–70s.

He refined his observations in compositions emptied of people: the unsettled seascapes of the nomadic 1880s, then the series paintings launched in the security of Giverny in 1890 with Haystacks, which slow down time to catch “the luminous atmosphere that brings dazzle to our ordinary lives,” as his friend Georges Clemenceau said. Finally, in the seclusion of his garden, Monet in the twentieth century turned the relationship between painting and nature inside out: he constructed his own landscape to provide motifs against which he could record his minute-by-minute perceptions, and in his Water Lilies series, he painted the surface of his little pond to reflect the infinity of the sky.

Monet built Impressionism on his confidence in the authority of a painter’s direct perception.

Painting is always an expression of personality; with Monet it went further. Only a man of tremendous self-belief could hold his nerve while transforming his private, fleeting impressions, which to audiences at the time looked like mere sketchy improvisations, into defining, iconic images—dawn breaking in Le Havre in Impression, Sunrise; his wife and son wandering through a meadow hazy in summer heat in The Poppy Field.

In youth, struggling against near-destitution, mockery and misunderstanding, Monet built Impressionism on his confidence in the authority of a painter’s direct perception. His independence, and his intense reactions, were fundamental to the project he set himself: his painting would be, he decided aged twenty-eight, “the expression of what I myself will have experienced, I alone.” At fifty, inaugurating the series painting, daring to pin down the same subject as one elusive impression after another—light falling thirty times on Rouen cathedral, poplars quivering by a stream from dawn to dusk—he reiterated the same impulse: “I am more than ever wild with the need to put down what I experience.”

As the frontier of his painting moved inward, Monet insisted that his method remained unchanged: obsessive attention to nature, stalking transient effects. But in 1927 the duc de Trévise described his pictures as abstractions: “skeins of kindred shades that no other eye could have unravelled, bizarre assortments of immaterial threads.” Few artists have lived and been productive for so long, and only Matisse has equalled Monet in producing late work which radically departed from his early manner, and yet was consistent with and developed inevitably from its first aims.

The distance from young to old Monet is shown by the gulf between his literary champions. In the 1860s Zola praised Monet through the prism of his own vigorous realism: “Oh, yes, here is someone with a temperament, here is a man among all these eunuchs…I congratulate him…for having an exact and candid eye, for belonging to the great school of naturalists.” Zola was especially drawn to the figure paintings, for Monet “loves our women, their umbrellas, their gloves, their lace, even their false hair and their face powder—everything that makes them the daughters of our civilization.” But as Monet’s path diverged from Zola’s, the novelist betrayed the friendship. His scathing novel L’Œuvre (1886) stars an impassioned painter who, bereaved, cannot stop himself seizing a canvas and depicting a corpse.

Thirty years later, in the first volume of À la recherche du temps perdu, Proust alludes to Monet’s water lilies. On a walk, the narrator watches the river Vivonne “choked with water-plants,” ugly and disordered, “suggesting certain victims of neurasthenia…and…those wretches whose peculiar torments, repeated indefinitely throughout eternity, aroused the curiosity of Dante.” Then comes a property whose owner “made a hobby of aquatic gardening, so that the little ponds into which the Vivonne was here diverted were aflower with water-lilies.”

In the depths, the narrator now sees “a clear, crude blue verging on violet, suggesting a floor of Japanese cloisonné. Here and there on the surface, blushing like a strawberry, floated a waterlily flower with a scarlet centre and white edges.” The gardener/artist has spun beauty and meaning from the chaos of nature and the mind. For Proust, Monet’s lilies symbolized the transformation of life into art.

The painter Elstir in À la recherche du temps perdu is partly based on Monet. In one of his seascapes, Proust writes, the artist “had felt so intensely the enchantment that he had succeeded in transcribing, in fixing for all time upon his canvas, the imperceptible ebb of the tide, the throb of one happy moment.” It is a description of the new painting which Monet inaugurated—painting which is expansive, fluid, and never stales because it is fed by the flux of so rich an inner life.

__________________________________

From Monet: The Restless Vision by Jackie Wullschläger. Copyright © 2024. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Jackie Wullschläger

Jackie Wullschläger is Chief Art Critic of the Financial Times. She is the author of the prizewinning Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller and Chagall: Life and Exile, which won the Spear’s Biography of the Year Award, and was short-listed for the Costa Biography Award, the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. She lives in London.