Own a Complete Set of the Paperback Experiment That Paved the Way for Penguin

For Sale: A Tower of Rare Bonibooks

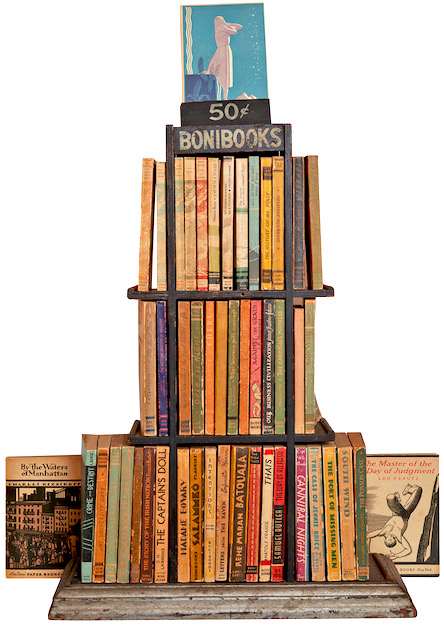

In the early 1930s, a bookshop window would have displayed the pretty, pictorial dust jackets of the latest bestsellers, say Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon and Pearl S. Buck’s The Good Earth. A compact wooden bookshelf stuffed with colorful paperbacks might also have commanded space and attention, its slightly off-kilter sign in all caps reading: 50¢ BONIBOOKS.

Even today, looking to modern eyes like a set piece out of John Huston’s Annie, the Bonibooks tower charms. Heather O’Donnell of Honey & Wax Booksellers is offering it for sale, brimming with the complete run of the 53 paperbacks published by Charles Boni between 1929 and 1931, for $4,200. Individually, only a handful of the books can be considered “collectible”—e.g., the first paperback edition of Moby-Dick—but as a whole, it is a rare relic of mid-century book publishing and bookselling.

“The shelf was why I bought it,” O’Donnell said. She purchased it from a fellow antiquarian bookseller in California a year ago and has enjoyed its presence in her Brooklyn office. Before that, she said, it was some book collector’s labor of love. “I have to assume that someone got the bookshelf and then started putting the books together.” Some of the titles, she added, are now hard to find. “It would take forever to put together this collection because a few of them only went through one printing and they were not the kind of books people saved.”

It was a transitional time in publishing, with anxieties about highbrow literature in lowbrow formats still being worked out.What exactly are Bonibooks? Let’s start with their originator, Charles Boni, who along with his older brother, Albert Boni, was a publishing pioneer. While still in college, he and Albert founded the Washington Square Book Shop in Greenwich Village in 1913, a literary legend celebrated in the 2011 exhibition, “The Greenwich Village Bookshop Door: a Portal to Bohemia: 1920-1925,” at the University of Texas at Austin. But the Boni brothers sold the shop to Frank Shay only two years after opening it in order to pursue publishing instead.

Their first venture was the Little Leather Library, a 30-volume set of miniature “classics,” bound in “lambskin” offered as a candy box premium. Later the set retailed for $2.98 via mail-order or in department stores. Their interest in the LLL was short-lived; they moved on and joined forces with Horace Liveright to form Boni & Liveright and launch the Modern Library in 1917. It was the same idea—reprinted classics in handsome leatherette—slightly elevated, but their partnership with Liveright was rocky, and they swiftly bailed. In the New York Times obituary for Charles, it is reported that the two factions flipped a coin to determine “who would buy out whom.”

The Bonis then started their own eponymous publishing house, where each man had his own pet projects. Reading between the lines, it seems they weren’t the best collaborators. “Neither of them worked well with anybody,” confirmed Jay Satterfield, head of special collections at Dartmouth College and author of The World’s Best Books: Taste, Culture and the Modern Library. Charles’s brainchild was the Boni Paper Books, a monthly paperback subscription club with the egalitarian mission to “place good books, well designed and carefully made, within the reach of any reader.” The series launched in late 1929 with Thornton Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey with elements designed by Rockwell Kent, but it fizzled out quickly. The annual subscription price of $5 proved too high in a Depression, and readers seemed reluctant to invest in paperbacks.

It was a transitional time in publishing, with anxieties about highbrow literature in lowbrow formats still being worked out. “There was an attempt to create a reading audience that he wasn’t totally sure existed,” said O’Donnell. “You can imagine that Boni was a man in continual pivot.”

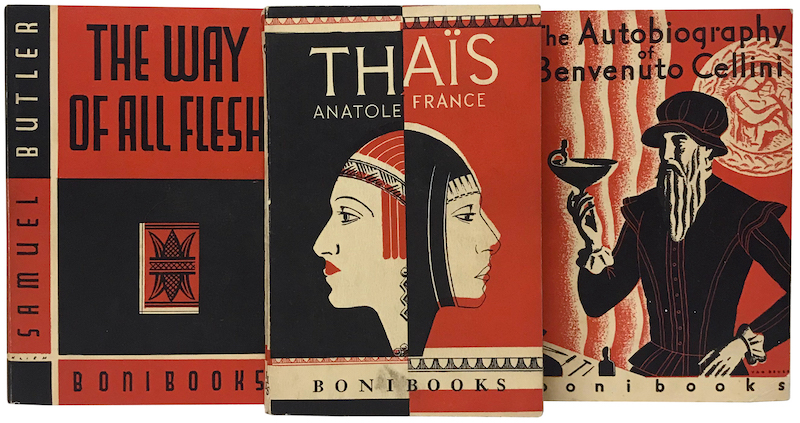

His new Bonibooks imprint was the natural successor to the Boni Paper Books. He ditched the club scheme but persevered with what we now call “quality paperbacks,” sometimes with slipcases to give each volume gravitas. His editorial selection, however, lacked cohesion; O’Donnell deemed it “Frankensteiny.” There’s the aforementioned Melville, but there’s also Mussolini, whose pre-dictatorship romance, The Cardinal’s Mistress, appeared in the series; there are Continental elites like Colette (Cheri) and Flaubert (Madame Bovary and Salammbo) as well as hard-boiled mysteries with titles like The Brooklyn Murders and The Port of Missing Men.

In total, 16 Boni Paper Books and 37 Bonibooks appeared before Boni called it quits in 1931. It seems he was always on the cusp of breakthrough, yet unable to sustain it. The Bonis were idealistic, said Satterfield, but “they weren’t capable of following through on their ideas, and it took other people to do that.”

It bears noting that Harry Scherman, the man who cofounded the Little Leather Library with the Bonis, parlayed his success with the series into a publishing juggernaut, namely the Book of the Month Club. And the men who scooped up the Modern Library, Bennett Cerf and Donald Klopfer, used it as the foundation to build Random House. As for paperbound reprints of “good” books, Allen Lane established Penguin Books in 1935, leading and propelling the paperback revolution during and after World War II.

Whether it was his idiosyncratic editorial choices, cultural angst over cheap books, or simply a bad economy, Boni’s series failed, but he was nevertheless prescient in his attempts to democratize literature—and to advertise and market it, which was considered “profane” by some, said Satterfield. As with Modern Library, Boni and his brother spurned that dichotomy. “They’re taking the highbrow/lowbrow thing and rejecting the whole notion of it. That’s where they shine and what makes them culturally interesting.”