The visitor sat at the table eating his little tangerine slices. Whenever things are excessively small, I can’t help but raise my eyebrows and put my hand on my heart, or at least where I presume my heart is. No one has ever had trouble making me stop misbehaving, all they had to do was offer me something miniature.

The visitor is delicate, so very delicate that he practically wafts apart. At first I didn’t notice, because he’s very good at hiding it. Anyone as delicate as the visitor is in grave danger. How easily he might end up in the clutches of some crazy person. My great-grandfather, for instance, was a well-known cult leader. Alas I was not so fortunate as to ever have met him personally. All I have of him is a single photograph showing him at a writing desk, his hair in a severe part, gaze aimed into a visionary future. I also find it fascinating that the sermons he gave were apparently improvised: he would let the Holy Scripture drop onto the pulpit, the beneficent hand of the Lord would make the book fall open at a choice passage, and he would thereby be presented with the subject of his sermon.

My great-grandfather might have put it thus: You have to trust the page that the Holy Book opens to when it falls, and anyway one is merely the servant of the Lord, there is nothing to do but carry out His will.

Next to the small town where I have come to rest, as if in a sarcophagus, there is a large mountain, rather like a pyramid, but not, like the actual wonder of the world, able to be sightseen from within, and furthermore capped with snow. One can, if one truly wants to, climb it. I personally refrain—by now the view’s been ruined for me and it’s no longer possible to see as far as I would like. I prefer to remain at the mountain’s feet. Sometimes the mountain’s shadow scares me.

I know everyone in this town but mostly act like I don’t know anyone. Something or other has happened to me on practically every streetcorner by now; various temporal strata are superimposed. There’s always quite a bustling crowd in the Roundel Bar, which is located right near my house; it was originally supposed to be open for only a hundred days, but that hundred has turned into thousands. The waiter changes every week, and each one is more appalling than the last, but they all keep their hair tied up tight on their heads, and even aside from that it’s safe to say there has never been anything interesting to see there. I always knew that I was ungrateful. My parents prophesied it early on, and I never denied it.

The visitor was uncharted territory. He materialized from the void. He got off the train, walked down the platform swinging his suitcases, and our gazes met. It’s not entirely clear to me whether the insane idea to come here was his own. I was standing on the other side of the platform, contemplating departure, or at least wandering around the train station trying to get an overview of all the destinations I might possibly travel to. But I’ve never set foot on a train.

I can’t deny it: the visitor seemed familiar the first time I stared at him through the gold-rimmed lenses of my glasses—or was it he, standing on the other side of the platform, who fixed his eyes warmly on me through the lenses of his, while we both knew we’d come from opposite directions and so would travel onward in opposite directions too, the next day or at the very latest the day after? It was this look from the visitor that burned into my mind and that I’ve been seeking in the looks of other people ever since that moment, and sometimes I find it, today it came from the moderator of a philosophical panel discussion on tv and was aimed at a young French writer.

They said on the radio that the animals in the zoo aren’t used to human beings anymore and take flight at the slightest human movement. Especially the flamingoes. The image of people drifting through the zoo while the animals take off for the great wide open is one I find pleasing.

Then came an interview with the head of tourism for the small town (into which I was involuntarily born and where I do not plan to die); he wanted to boost tourism by presenting the little town as a major metropolis. This statement struck me as so nonsensical that I didn’t know what to do with myself. At the Roundel, large flakes from a croissant had been scattered across the bar with its thin plastic coating of fake marble. They glittered gold in the sun. The mountain, the head of tourism went on, was a great attraction already, of course, but the aerial tramway was tottering, the cable cars swinging ominously—renovations were urgently needed.

I didn’t make a habit of going to the bar in the middle of the day, but the recent appearance of the visitor had driven me out of the house that morning to take up the search for him.

Outside, people I was only able to perceive as silhouettes walked up and down the streets. I observed a mother resignedly pulling her berserk child by the hand. Sitting at the marble bar, one leg crossed over the other, I imagined that only teeny-tiny people lived in this small town, riding around on teeny-tiny bicycles and tossing down ristrettos from teeny-tiny coffee cups. I had no problem picking up the entire Roundel Bar in my hand, turning it around, and examining it from all sides, while the people sitting on the barstools shrieked and tried to hold on; their teeny-tiny drinks had already fallen, plummeted, and landed on my jeans as little drops. The people, now hanging on for dear life, stared at me with wide minuscule eyes as I tore the Roundel in half down the middle, like a donut. I imagined the small town getting smaller and smaller, shrinking down to a tiny point—I alone remained large, so I no longer fit in it. Then it occurred to me that this was already the situation.

The radio was broadcasting a report about the increasing wave of violence against caregivers. The bartender turned the radio down, and the voices drifted away.

__________________________________

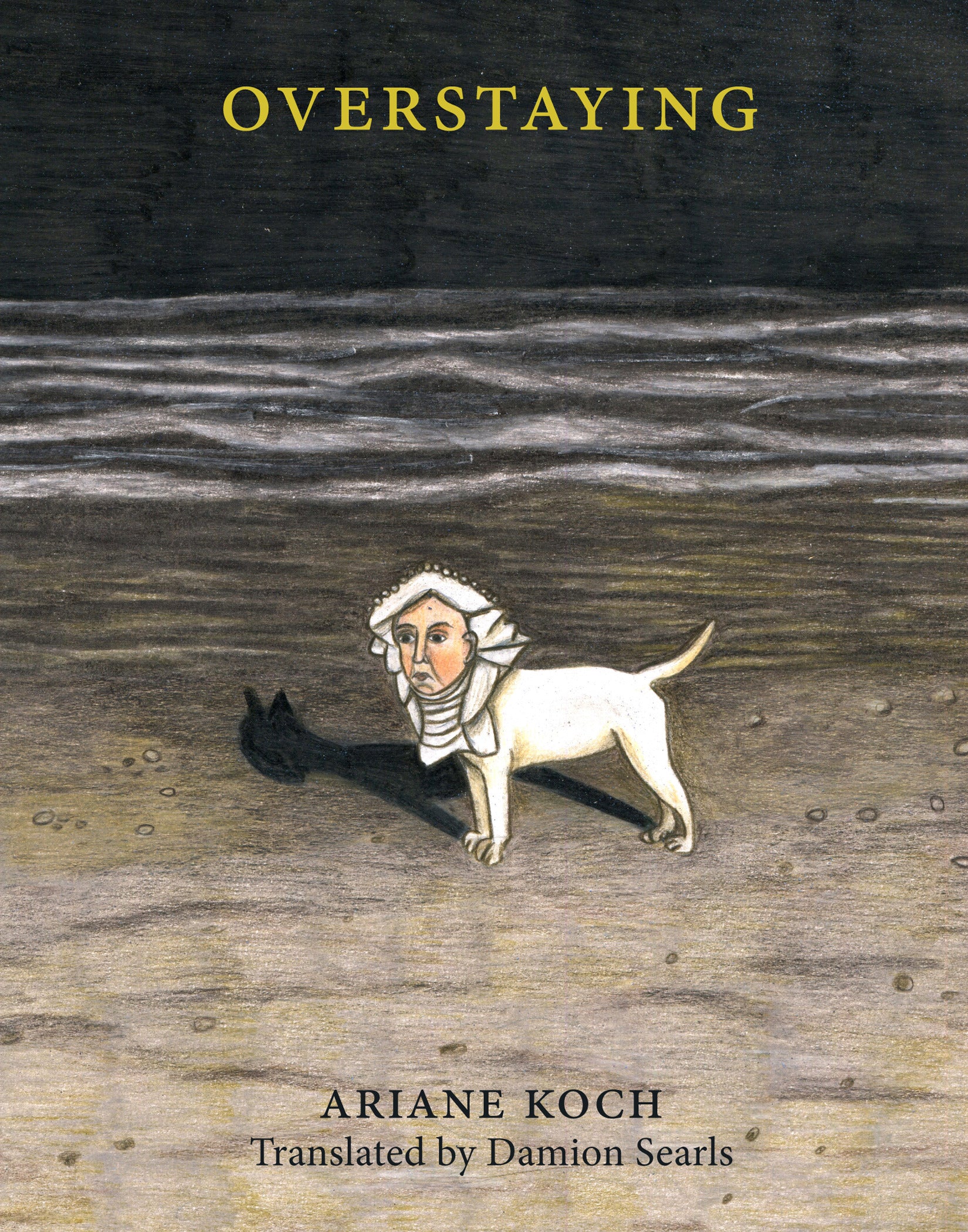

From Overstaying, by Swiss author Ariane Koch, translated by Damion Searls, out now from Dorothy, a publishing project. Copyright © 2024 by Ariane Koch.