Outdoor Manual: Benjamin Wood on Taking It Outside

“Moved outdoors, my novel finds its purpose and momentum.”

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Every story has an equilibrium to be disturbed, and this one opens with a stranger on my doorstep. He stands bright-eyed beneath my porchlight with a sheepdog at his heel. It’s mid-December, sometime after six. He’s rattled at my letterbox to drag me from the dinner table with my family, but he’s unapologetic. He’s just bought the house next door. A private sale, he says, completed on the quiet. The planning permits are in place. Work on the extension will begin just after Christmas. There might be, he says, a bit of noise.

In January, the drilling starts. This coincides with my own plans to write. I’m trying to get a novel moving in the room adjacent. Every day, from eight till five, I hear the builders’ radio behind the party wall, their shouty banter, the electric fizz of sawblades, digger engines, skips being loaded, lorries turning round outside my window, winching beams of steel. The manual labour soundtrack I grew up with but could never play myself.

The bench is hard and damp. I won’t be staying long. But then—a strange sensation, like the warmth returning to the numbness of my hands beside a fire—I get the urge to work.

For weeks, I try to block this out with instrumental music in my headphones but can’t concentrate or disconnect. Soft earplugs make me feel as though I’ve got the bends. I do my best to relocate. To local cafés. Libraries in London. Still, my brain won’t function and the novel’s in a state of atrophy. Late one night, I hear the builders sawing metal, but it’s just the squeal of tiny violins inside my head. Self-pity, keeping me awake. A peal of shame. The truth is, I don’t want to write another book at all. This feeling was already setting in, two years before the stranger rattled at my letterbox. My interest in fiction—reading it, composing it, discussing it—is nothing but exhaust fumes I’ve been trying to disguise as inspiration. The builders have relieved me of this duty.

In the morning, there’s a concrete lorry parked outside, preparing to pipe in a motherlode. The sun is shining but I cannot hear the birds above the engine. I decide to leave the house. A walk of desperation. Force of habit makes me bring a notebook and a pencil with me. I’ve no purpose in my mind except to leave. I don’t go far, just down the lane to the old church, enveloped by the trees. The grass is knee-high at the gravestones near the path. Beloved men and women buried in the age of Queen Victoria, some who share my father’s year of birth, and others buried at the age I am today. A peace comes over me I haven’t felt in months. There’s quiet here and plenty to go round.

At the shaded end beyond the chancel, there’s a garden of remembrance. I used to stop there every now and then, whenever I went walking in the neighbourhood, to drink a cup of coffee on the bench. This morning, I sit down to be alone, unbothered for a while. The bench is hard and damp. I won’t be staying long. But then—a strange sensation, like the warmth returning to the numbness of my hands beside a fire—I get the urge to work.

The words arrive before I’ve got my pencil ready. I can hear them as distinctly as the birds again. The act of scrawling them upon the page is tangible and pleasing. I look down and the paper is near empty, but it doesn’t sadden me the way the blinking cursor does, the bare white space upon the screen. Where has this feeling been so long? Expecting me to show up at this garden of remembrance, I suppose.

I do remember. I stay seated on that bench for hours, until I need to fetch my sons from school. The next day, I go back again. A flask of coffee and a cushion in my bag. A pencil sharpener and a good eraser. Leave the builders to their concrete. This is my routine now.

Moved outdoors, my novel finds its purpose and momentum. More than that, it helps me to regain the pleasure of the job. That drift beyond the influence of ordinary time while I’m at work, the world and all its problems muted. I’ve handwritten parts of other novels in the past, but only paragraphs at the beginning, stubborn clots in scenes already underway. This feels much different. On a bench within a graveyard, no clear signal on my phone, without the internet. I cannot stop to research arcane facts and details on a whim; I cannot hit the backspace key to kill a sentence in one click. Whatever I write down, I have to listen to it first, make certain I can hear its proper formulation. I press heavily upon my pencil, knowing it will be a pain to rub words out. By afternoon, a debris of eraser rubber coats my lap. I brush it off as though it’s sand, and realize—I needed this.

It’s brought me closer the subject of my novel, Thomas Flett. A shanker who must ride out with a horse and cart for miles to reach the shallows at low tide to earn his living, catching shrimp. It helps to write his story in the open air. It feels more logical to craft his daily work by hand. He wears his oilskins out at sea: I have a set of waterproofs and an umbrella. He works in any weather, so I do the same. Are you method writing? my wife teases me at dinnertime. I don’t know what to call it, but it helps to have the rain above my head when I’m in need of an articulation of its sound. It’s meaningful to feel the biting cold when Thomas does. It’s good to walk home with a callus on my finger, knowing I have grafted in my own small way. I might not have a chance to work like this again.

_______________________________

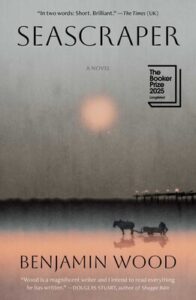

Seascraper by Benjamin Wood is available via Scribner.

Benjamin Wood

Benjamin Wood was born in 1981 and grew up in Merseyside. Seascraper is his fifth novel. His previous works have been shortlisted for the Costa First Novel Award, the Commonwealth Book Prize, the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, the RSL Encore Award, the CWA Gold Dagger Award and the European Union Prize for Literature. In 2014, he won France’s Prix du Roman Fnac. He is a senior lecturer in creative writing at King’s College, London, and lives in Surrey with his wife and sons.