Out of This Disaster, New Approaches to Art May Emerge

Hal Foster on What—Or May Not—Come After Covid-19

I suck at predictions. Surely with the financial meltdown in 2008 the art market would crash and the art world would be transformed. Wrong. Surely the Occupy movement would prompt museum directors to rethink excessive reliance on plutocratic patrons. Wrong again. I could list other failed forecasts, but maybe these are enough to suggest why even I don’t listen to me anymore. So please don’t ask me what lies ahead for the art world if and when Covid-19 loosens its grip. I haven’t a clue.

I do have a few thoughts, though, on what has happened lately; that’s the subject of my book What Comes After Farce? Art and Criticism as a Time of Debacle. The current state of emergency didn’t begin in March 2020; it runs back to September 2001. Since 9/11, in the US and elsewhere, we have lived in a world where the rule of law is sometimes suspended and often spotty, in ways that have put countless people at varying degrees of risk. The virus has just made this all the more blatant.

Historically, the avant-garde aimed to contest the oppressive presence of law, whether that law was understood as artistic, social, political, or all three at once. But how are artists, writers, and others to respond when law becomes highly erratic, arbitrarily enforced one moment and just as arbitrarily absent the next? How to create, how to survive, in a state of emergency?

That is one political line of inquiry in my book. Another thread is financial; it concerns the neoliberal makeover of art institutions during this same period. Given ever greater inequalities in wealth, it is no surprise that both markets and museums expanded enormously, and that a new Gilded Age of cultural ostentation emerged (more than 200 private museums have appeared since 2000). What is a surprise is how otherwise progressive architects leapt to design these monuments to neoliberal magnificence, and that otherwise progressive artists agreed to fill them. The old bugbear—when is money clean enough or, conversely, when it is too dirty?—has come back with a vengeance, and it is hardly a question for museum directors alone.

There is a technological concern, too, which traces recent transformations in media, in particular the advent of “machine vision” (images produced by machines for other machines), “operational images” (images that intervene in the world rather than represent it), and the algorithmic profiling of people as data points. Today most of us look out on a world that has moved, technologically and politically, beyond our control, and this extreme situation has prompted extreme formulations by artists and critics alike.

Such is the opportunity in the current crisis: to transform disruptive emergency into structural change.

Thus, for example, Trevor Paglen sees art as a “safe house” in a world given over to digital surveillance, while Claire Fontaine imagines it as a “human strike” against all scripted identities. Sometimes in such harsh light it is difficult to distinguish between the critical and the dystopian; sometimes, too, the ambient nihilism of the neoliberal order seems redoubled as much as challenged.

What does all this have to do with “farce”? My title is a riff on a famous line in Marx: “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” The tragedy at issue here is the seizing of dictatorial power by Napoleon in 1799, and the farce is the repetition of this act by his nephew Napoleon III in 1851. How could the Bonaparte clan get away with the same power grab twice? According to Marx, the repetition at least clarified one thing: the bourgeoisie was only too ready to ditch its democratic values—liberté, egalité, fraternité—if doing so meant that it could retain its economic domination.

In our time Trump has performed a similar clarification: his plutocratic backers regard the trashing of constitutional laws, the scapegoating of immigrants, and the mobilizing of white supremacists as a small price to pay for even more capital concentration through financial deregulation, tax cuts, and crisis bailouts. And like the lumpenproletariat in France then, his angry followers in the United States today are tricked by the old promise that they will be protected from exploitation even as they are delivered all the more completely to it.

So if farce follows tragedy, what follows farce? Nothing necessarily; nothing is guaranteed. At such a fraught time one might be forgiven for clutching at etymological straws. Originally a “farce”—the word derives from the French farcir, to stuff—was a comic interlude in a religious play. A farce might be understood, then, as an in-between moment, along the lines of “the morbid interregnum” detected by Antonio Gramsci circa 1930. At the very least an interlude suggests that another time will arrive.

This is where the other term in my title, “debacle,” comes into play. It too derives from the French, for “downfall, collapse, disaster,” but its root is débâcler, “to free,” from the Middle French desbacler, “to unbar,” and its literal meaning is “the breaking up of ice on a river,” as in a flood in spring. A debacle is thus a sudden release of force—likely for bad but also maybe for good. “Debacle” might even point to a dialectic of breaking and making otherwise with regard to conventions, institutions, and laws alike. Such is the opportunity in the current crisis: to transform disruptive emergency into structural change, or at least to pressure the cracks in the socioeconomic order where unjust power can be resisted and reworked.

__________________________________

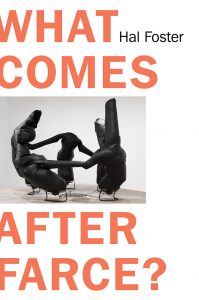

Hal Foster’s What Comes After Farce? is available from Verso Books. Featured image: Claire Fontaine, P.I.G.S., 2011. Matchsticks, plaster wall, concealed corridor, HD video projection, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the artist and MUSAC Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León, León. Photo by Nacho López.

Hal Foster

Hal Foster, Townsend Martin Class of 1917 Professor of Art & Archaeology at Princeton, writes regularly for October (which he co-edits), Artforum, and The London Review of Books. He is the author of many books, including, most recently, What Comes After Farce? Art and Criticism at a Time of Debacle (Verso Books, 2020), and Conversations About Sculpture with Richard Serra (Yale University Press, 2018). Brutal Aesthetics, his 2018 Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, will be published by Princeton University Press in fall 2020.