The night before we load you into the crate and watch as the helicopter carries you off to the undisclosed location to drop you into the Atlantic Ocean, we eat dinner as a family. I roll your wheelchair to the head of the table, which has always been a little too small for five, so that it’s clear to everyone who’s being honored. I’d hoped to grill up a few of those rib eyes we’ve got in the garage freezer—it seemed the right occasion for it—but then Avery recalled how you’d always loved Rosemary’s braised chicken back when you were still on solid food, and so, in honor of you, even though you aren’t eating, that’s what we eat.

We try conversation for a little while. I think about going around the table and having everyone share their favorite memories with Grandpa, but I know in order to do that I’ll need a really good memory, which I don’t know if I have. As I try to come up with something, Ernest turns on the little TV we keep on the kitchen counter. I assume Rosemary will object, but she’s busy checking the drip on your IV and I’m busy remembering, so we let it go.

As we eat we watch Little Winston, part of the wholesome black-and-white hour of family programming that usually rounds out our dinnertime. They’re airing the Father’s Day episode, which we’ve seen a hundred times, but I think we all realize the importance of watching it again today, especially for the boys.

Little Winston and his father, Big Al, sit on the front stoop of Big Al’s Gas ’n Fixit. They’ve just returned from watching Chester, Big Al’s father and Little Winston’s grandfather, get crated away. Their untouched glasses of lemonade sweat in the afternoon heat. Little Winston is folding and unfolding his sausagey fingers on the lap of his blue overalls, which he always does when he’s upset, and Big Al is trying to console him.

“It makes me scared,” Little Winston says, tears poised to roll on the edges of his cheeks, “to think that one day they’ll carry you off in one of those big crates, Big Al. That one day they’ll drop you into the sea at the undisclosed location with a bunch of strangers. That I’ll never see you again.” “I know, son,” Big Al says. His thick mechanic’s arms, normally crossed over his grimy blue work shirt in stoic disapproval of Little Winston’s comic hijinks, are now on the boy’s shoulders, his rough, greasy hands straightening Winston’s cowlicked hair in one of the series’ rare moments of paternal tenderness. “When you get to be my age, you’ll understand.”

“I’m not gonna be able to do it, Big Al,” Little Winston sniffs. “I’m not gonna know when or how.”

“You will,” Big Al assures him, his hand on the boy’s back. “You will. Just follow your heart.”

“I love you,” Little Winston mutters.

“Just follow your heart,” says Big Al. “That’s all I’m doing here.”

“I love you, Big Al,” Little Winston repeats.

“I love you, too, little buddy,” says Big Al. “I love you, too.”

Gurdy Bills, the actor who played Little Winston, is an old man now, and kind of a local celebrity. He retired to an enormous house up in the north foothills, and resurfaces from time to time for little events and fund-raisers. I’m always surprised that people still come out to see him, since he never did another show after Little Winston. I remember once, not long after we crated Mom, we took you and the kids down to Ainsdale to watch him cut the ribbon on the new Pine Pleasant Mall. It was some crowd.

I ask Rosemary when she expects we’ll read they’ve crated Gurdy Bills. I even smirk a little, thinking this is a bit ironic, considering what we’ve just watched, and would have enjoyed a brief discussion about how the years catch up with all of us eventually, how we should take the time to savor its fleeting preciousness, etc. I think maybe this is something the boys ought to hear, that the time is right, but Rosemary is in no mood. This episode always makes her well up, and she’s especially tearful tonight. She tells Avery to sit on her lap so that she can stroke his downy arm hair and make small, popping kisses against his ear. Avery knows his mother needs him, and though he’s old enough to sense that being babied is something he should resist, he doesn’t. At the other end of the table, Ernest has gathered the bones from our plates and is attempting to reconstruct the entire chicken.

When Rosemary’s done mothering him, Avery asks if he can be excused from the table.

“Kiss your grandfather good night,” I say.

“Gross,” Ernest says, but Avery understands. He rounds the table to you, leans over the tray of your wheelchair, and kisses your cheek the way he kissed mine back in the days when he used to kiss me, as young boys sometimes do before their fathers put a stop to it. But it means something to me in this moment, watching my son give you, my father, this sincere kiss good-bye, which is why I think you and everyone else will forgive me when I say that he is the good one and, of my two sons, the one I prefer.

Then you start having one of your fits.

It’s a shame that Avery is so close, and he’s just finished such a sweet thing, such a gentle act of affection, because your fits terrify him. Right away, his chin rumples like a raisin to lock down incoming tears. I try to steady you so that Rosemary can secure the straps to your head and arms. Avery disappears upstairs to cry out of sight, no doubt assuming that his act of love has somehow caused your spasm. You pull against the straps like a weight lifter, drool snaking down your chin in little fingers. As I force your shoulders against the back of the chair, I can’t help blaming you a little for ruining what had been a really beautiful moment, because a chance like that doesn’t come again, and now Avery, who is already extremely sensitive, will always have this crappy memory attached to kissing his grandfather the night before he was crated.

*

Hours later, while Rosemary readies the boys for bed, I put a couple bottles of good beer in my coat and wheel you out onto the porch so that we can enjoy the lake at night. It’s our lake, yours and mine, and now mine and my sons’. For all the fighting, all the hurt feelings, the years of not talking even before you lost the ability to speak, we still end up here, you and I, looking at a lake full of stars.

For some reason, one of the beers is much warmer than the other, almost room temperature, but rather than spoiling the moment by running back in for another, I suck it up and decide to just drink a warm beer. I put a straw in the colder one and set it on your tray, then lift my warm one and say, “Well, here’s to you, Dad. We sure will miss ya.”

I take a drink while you let the straw find your mouth. You manage a few sips and seem pleased with them. We look out on the lake, admiring the way its stillness makes everything around it seem not as quiet. I suddenly remember the memory I should have remembered at dinner, the day you taught me to catch tadpoles, which we used to keep in an old mason jar with a few inches of water. You showed me how controlling the water level prevented them from maturing into frogs, and how nice it was to keep tadpoles as they were, blindly swimming around until they died and we replaced them with new ones. It’s a practice I’ve passed on to the boys, who’ve lived their whole lives with jars of black blobs sitting on their windowsills, never imagining they should grow to be anything more than what they are.

*

That night I dream that Mom and I are standing on the small dock just beyond the house. She’s the age she was when I was in high school, still decades away from crating. She tells me that you died in your sleep. In the dream she calls you “Daddy,” which she never did in life. “Daddy’s gone,” she says, and I feel the relief whistle out of me like an untied balloon. You’re gone. I don’t have to crate you. I’m so happy I dive into the lake, where the dream lets me breathe freely, the warm water hugging me close until I wake up.

“We’ve promised Ernest your room after you’re gone, but the sight of him mentally replacing your things with his made me uneasy as a parent.”

I go to your room to check on you, the way Rosemary will on the boys after she’s had a bad dream about them, or a bad feeling, or just wants to know that they’re safe. Like you, I’ve never put much stock in dreams. I’m not checking on you because I think mine has come true, though it would definitely make things easier on everyone.

You have enough blankets to keep you warm, and your IV bag is full and dripping properly thanks to Rosemary, who always puts you to bed, and again I realize how lucky I am to have a wife who treats you like her own. As I get closer I can see that some of the sheets are twisted around you, which means you’ve been fitting in your sleep. I consider strapping you to the bed for the rest of the night like we sometimes do, but I can always tell from the looks you give me in the morning that you’ve slept badly, and I don’t want to get one of those looks tomorrow, so I leave you be.

I realize now that we could have made the room a little nicer for you. The curtains are old and faded, and there isn’t much on the walls except for a print of a sandpiper-ridden beach that’s been hanging there since we moved in. It’s nothing like the boys’ room, which we’ve always tried to keep comfortable and cheerful to make up for the fact that they share.

The other day I caught Ernest standing in your doorway, sizing up the place. At first I thought he might be mustering the courage to come in and spend some time with you, to talk to you or hold your hand for once in his life, but then I remembered that Rosemary and Avery had taken you for one last stroll on the little boardwalk that circles the water. We’ve promised Ernest your room after you’re gone, but the sight of him mentally replacing your things with his made me uneasy as a parent. Yesterday he showed me a floor plan he’d drawn. He pointed to where his TV will go, and described the loft he wants to build to free up more floor space. Whenever he looks at you now with that cool, unsmiling stare of his, I worry that maybe he isn’t turning out the way I’d like him to.

On the dresser are some of your old photos. There’s a close-up of Mom when she was the age I am now, and one of you and your brothers as kids on a first day of school. They’re too far from the bed for you to see, which means you probably haven’t seen them in a while.

I get an idea. I take the photos downstairs and tape them to the tray of your chair, so that tomorrow in the crate, when you look down, you’ll see them, Mom and your family and everyone looking up at you. I add one of you and me from that trip to the Kenner River when I was eleven, just a few months after we crated your dad, which is probably why you planned it. We took our time canoeing the river, with Mom driving ahead each day to lay out a picnic at the spot where we’d break for lunch. The picture, which she must have taken from the shore, is of the two of us on the water, our toes dragging in the lazy current. I also tape down the photo from the mantel that we used for this year’s Christmas card. We’re at the state fair, huddled around a pumpkin that’s shaped like a pig. Sure, Avery’s ruining it a little with that ridiculous pig face he’s making, but we all seem pretty happy, even you, in your chair with Rosemary’s hands clasped around your neck in an adoring way. I head back to bed, but I’m so pleased about the photo idea that it’s hard to drift off.

*

That morning at breakfast Avery gives you a picture he’s drawn. It shows a crate, one of the modern titanium models with a wide pressure-resistant window, through which we can see a man waving. Avery says this is you. The crate is set against a background of deep blue, suggesting that it’s already been dropped at the undisclosed location. Outside the crate, walking along an ocean floor next to a single starfish and a lone hermit crab, is another figure wearing a kind of space suit, waving back. Avery says this is him. I want to ask him why he didn’t draw the crate before the drop, so that we could all be waving together, but for a moment I think the way Rosemary encourages me to think—that is, with patience, with understanding—and I don’t ask. Instead I tell him it’s a great drawing. I tell him that you like it, though you’re not looking at it. You’re looking at him, but in a cross-eyed way that I can tell is making him uncomfortable, and I’m mad at you all over again, because this is your chance to make up for last night and you’re blowing it.

As we head to the car, Ernest calls shotgun. I tell him we’re giving you the front seat today so that you can get a good view of the lake one last time before you leave. He asks if he can have shotgun on the way back. I pretend not to hear him and wheel you around to face the house.

“There’s the house, Dad,” I say.

It doesn’t look great. I’ve been meaning to repaint, especially the shutters and trim, which have shed pretty much every trace of their original blue. Half the porch balusters are missing, kicked out by Ernest during one tantrum or another. I honestly don’t know if you have any sentimental attachment to this place, and suddenly it occurs to me to drive you up to see the old family home in Clark County where you grew up. I don’t even know if the house is still there. The drive is forty-five minutes each way, and crating check-in is at eleven on the dot.

Maybe just this house is enough. Maybe you can look at this one and think of the other one. Standing behind the chair, I can’t tell where you’re looking, so I walk around to check. Rosemary has dressed you in your gray linen suit—baggy at the shoulders and around the waist from all the 10 weight loss—and your bolo tie with the silver deer-skull slider, which is not what I would have chosen, even if it is classic Dad, because I guess I have a greater sense of symbolism than she does, but it’s too late now. You’re fixed on a patch of goldenrod crawling out from under the porch, staring at it blankly, like if I were to poke you in the eye my finger would just go right through, and while I’m disappointed that you don’t seem to be lost in a moment of pleasant reminiscence, at least you’re not noticing the second-floor gable, which is sloughing off shingles like it has some kind of disease, or the man-size weeds choking the last bit of life out of the raspberry bushes Rosemary planted a million summers ago.

“Yep,” I say. “That’s where we lived.”

*

We make it to the mall parking lot just fine, but I’ve forgotten that there’s a Sugar Scoops in this strip, so right away Ernest starts howling for a cone. I tell him there’ll be cotton candy and popcorn at the loading site, but even I know that can’t compete with Sugar Scoops, where they mix cookie chunks and gummy bears into your ice cream right in front of you. I decide maybe this is just Ernest’s way of getting into the spirit of things, of making the day special, so we spend several extra minutes ordering everyone a cone before crossing the baking sheet of black asphalt to the loading site on the other side of the parking lot. I imagine you must be roasting alive in your suit, because I’m roasting alive in mine, but maybe linen breathes better than a cotton-wool blend. Rosemary has mashed some of her ice cream into a soup, which she’s feeding you. Strictly speaking, she’s not supposed to do this, as it’s still technically solid food, but you seem to enjoy it. You look straight at her as she spoons the pink goo between your lips, and you move your mouth in a way that suggests you at least remember how to eat. It’s a nice moment for the two of you, so I don’t say anything. Instead I find the check-in desk and write your full name and date of birth on the white and yellow forms.

We pass through a sort of plywood gateway into the event area, where we’ll wait until the boarding starts. Inside are the cotton candy and popcorn booths, and a guy standing next to a helium tank with a fistful of balloons. Nearby, a portable stereo plays patriotic rock anthems behind a juggler doing five bowling pins at once. At the center of everything is the crate. Through its enormous picture window we can clearly see the three dozen or so empty red velvet seats like the skybox at a baseball stadium. The silver cables riveted to its frame run to a decommissioned military helicopter dozing at the edge of the lot.

I remember when we did this with your dad. The whole thing seemed weightier then, maybe because there was a live brass band instead of a portable stereo, or because in those days we held cratings in city parks and squares instead of mall parking lots, or maybe I was just young and everything adults did seemed bigger and more important. I remember one of the clowns made me a balloon giraffe, and your father asked, like some do, not to be taken, to be held over till the following year. Next year, he promised, he’d be ready. I don’t remember what you did, if you wept or tried to argue with him, or if you simply stood by like I am now. I remember that he had the good sense to ask only once, but even that small moment of pleading caught me off guard, and I couldn’t shake it for weeks after. When it was time for the helicopter to take off, I couldn’t look, afraid I’d see his face through one of the portholes, which at that time were only big enough to show faces and nothing else. Instead I turned to the clown with the balloons, who of course by then wasn’t clowning at all. He was watching the helicopter and the crate fade into the distance with everyone else, his makeup and rubber nose unable to hide the fact that, despite knowing no one in the crate, and probably attending events just like this one several times a year, he still felt something strong and meaningful watching it go, and as I watched him watch it, I realized what a sin it was to look away.

I wait with you in the event area while Rosemary takes the boys to get balloons. I’m at least happy to see that people still dress up. All of the adult men are wearing neckties, and it dawns on me now that my powder blue tie with the little crests and coats of arms would have gone well with the suit you’re wearing. Better than the bolo, the hollowed-out sockets of the skull reminding us all in the most tasteless way why we’re here, which I can’t believe Rosemary didn’t consider as she was dressing you. “Should he wear the deerskull slider?” she could have asked me. “You know, the one that makes him look like the worst sort of backwater lake rat? Or do you have something more appropriate to the solemnity of the occasion?” And I would’ve pulled out the powder blue tie, with its little chevroned shields and rearing lions and fleurs-de-lis, and she would’ve smiled, and nodded, and noted to herself how fortunate she was to have a husband who understands the importance of detail within the context of greater events.

The two men standing beside us wear burgundy suits and matching ties, like performers in a men’s choir. The son is tall and proud, with a steady hand on his father’s shoulder. The father’s hands shake at his side, but not out of fear. Both his face and his son’s are cheerful and calm, plump and pinchred in the cheeks, as if this is exactly the day they’d hoped to see from the moment they woke up. I find myself standing straighter just looking at them, and I ease your shoulders against the back of the wheelchair so that you’re slouching a little less.

“Some crate, eh, Pops?” the son says to the father. “Nothing like Granddad’s. That thing was just a steel box with metal seats and a few glass portholes, remember? And what about his dad’s? Can you believe that once upon a time the crates were actually crates? As in, made out of wood? Not even airtight! Those dads drowned as they sank. Not exactly what I’d call respect for your elders. But harder times, I suppose. This, though—just look at it. Do you have any idea how many psi these reinforced frames can withstand? Boatloads, Pops. Just boatlaods.”

The father regards the crate with a satisfied expression, as if to say that, indeed, it is some crate.

“And don’t forget the pressure-resistant window,” the son adds. “You’ll be able to see those dolphins nice and clear. How about that, Dad? Dolphins all the way down, keeping you company.”

I’ve heard of this—reports of dolphins gathering at the undisclosed location. I want to ask the son privately if this is just something cheerful he’s decided to say, or if he has actual evidence of dolphins, if he knows someone who can confirm it.

Regardless, I’m hoping that you heard him. Dolphins, Dad. Maybe whales and anemones, too, and great schools of silvery fish. You’re studying Avery’s underwater picture, which Rosemary clipped to your tray with the clips we use to hold the newspaper in place when we think that you might like to look at it. I wish that Avery had drawn a few dolphins swimming alongside the crab and the starfish, to give you a better sense of just how comforting this whole business is going to be. Then I remember the photographs under the drawing. I unclip the edge of the paper, and it furls lazily to one side, revealing the shot of you and me in the canoe, our arms and knees sunburned, our chins pointed intrepidly forward. This, I think, is the image you should be contemplating, and I want to point it out to you, to remind you of that day and all that hopefulness, but you’re not looking down anymore. Instead, you’re looking where everyone else is looking, at a man moving slowly from the check-in desk to the crate, followed by a small assembly of beaming fans.

It’s Gurdy Bills. Little Winston himself.

He’s balder and rounder than he was in his mall-opening days, but still has the aura of a television personality, the confident walk and eyes. He wears long white robes and carries an old-fashioned sickle in one hand and a baby in the other. The baby, wrapped in its own little toga, is sucking on what looks like an hourglass. The costume is meant to amuse—Gurdy Bills is, after all, a performer, a comedian—and many laugh and applaud what they see. Even the juggler stops to watch.

Rosemary rejoins us with the boys in tow, each holding a balloon and a sky blue plume of cotton candy.

“Isn’t that something,” she says. “With a baby and everything.”

Standing beside Bills is a less bald, less round man wearing blue overalls and a gelled cowlick. We assume this is his son. After handing off the baby, Bills turns to this man, and the two begin a little recital.

“It makes me scared,” Bills’s son says clearly, cheating his stance to the side and projecting so that everyone can hear him, “to think that one day they’ll carry you off in one of those big crates, Dad. That one day they’ll drop you into the sea at the undisclosed location with a bunch of strangers. That I’ll never see you again.”

“I know, son,” Gurdy Bills says. His expression is focused and concerned, and in spite of the ridiculous getup, and the fact that we’re all standing in the middle of a strip mall parking lot, the scene is suddenly intimate. “When you get to be my age, you’ll understand.”

“I’m not gonna be able to do it, Dad,” Bills’s son says. “I’m not gonna know when or how.” “You will,” Gurdy Bills says, a hand on his son’s overalled back. “You will. Just follow your heart.”

“I love you,” Bills’s son says with a smile.

“Just follow your heart,” says Bills. “That’s all I’m doing here.”

“I love you, Dad,” Bills’s son says. Now he’s looking out at all of us.

“I love you, too, little buddy,” says Gurdy Bills. “I love you, too.”

Everyone cheers. Even Ernest. He’s smiling and clapping like it’s the best thing he’s ever seen. I wonder if we shouldn’t take Ernest to see more live theater, maybe a show now and then down at that little dinner theater place in Phillipsburg that Rosemary’s always talking about. Maybe it’s the sort of thing that would help him locate something different and good inside himself.

Then Gurdy Bills raises a hand, and everyone is quiet. “We go to see our fathers,” he says. “We are not afraid.” And with that, he hugs his son, kisses the baby in the toga and the woman holding him, and climbs the ramp into the crate.

“How about that, Dad?” I say to you. “In the same crate as Gurdy Bills.”

*

The men begin to file into line. Rosemary bends to kiss you on the cheek, then sniffles into a Kleenex. Avery cautiously pets your shoulder, afraid to get too close. Noticing his rolled-up drawing, he gently slips its corners back into their clips, the photographs of the family and our day in the canoe vanishing once again beneath a scribbled ocean. Ernest is looking at you, and while it isn’t exactly a loving look—more of a standoffish look, the look of a gunslinger just before he draws—it’s the last moment you’ll have with him, so I don’t want to interfere. Eventually he tucks his sprig of cotton candy, which by now is just a cardboard tube and a few thin wisps of blue sugar, into the space between your stomach and the tray. As I wheel you off, I want to believe—need to believe—that he was sharing the last of it with you and not just throwing it away.

“Is this the moment they think I wanted? Is this any kind of send-off for a man who has done, if not great things, then at least good things?”

We’re at the end of the line because you don’t need a seat. There’s an alcove for your chair and two others in the front row. While we wait, I try to think of some final thing to say to you.

There isn’t enough time to get into the whole money thing, even though I want you to know I don’t care about that anymore. I could just say that, just say, “I want you to know, Dad, I’m not sore about the money anymore,” but without going into the reasons why I don’t care, why I actually stopped caring a long time ago but couldn’t say so because I needed you to believe I still cared, it would just sound like I’m letting you off the hook. I could promise that I’ll always look after the old family home in Clark County, except, like I said, I’m not sure it’s still there. Besides, I want to send you off with something forward-looking. Something hopeful. Through the window, I can see the other sons whispering into their fathers’ ears, saying soothing, important things. Some are in tears. Some are burying their faces in their fathers’ laps, begging forgiveness for this thing we are about to do, or a worse thing that came before it. Some say nothing. None of the fathers are asking not to be taken, which is rare. Maybe they don’t want to embarrass themselves in front of Gurdy Bills, to be the one blubbering and begging while the great actor sits smiling in his white robes, ready for the plunge.

I want to know what Gurdy Bills’s son is saying to him. I want to know what you said to your father. I want to tell you not to worry, but I don’t think you are worried. I want to tell you not to be afraid, but there’s no sign of fear on your face. I can’t tell if you’re comfortable. I don’t know if you’re content. You give nothing away.

Nozzle heads hang from the ceiling inside the crate, waiting to release anesthetic gas when you reach critical depth. I wish Avery could see these. I don’t know if he knows about them, but he should, to understand that we’re not monsters. That we care what happens to you after you drop.

As soon as I ease your chair into the alcove, you start having one of your fits. Your wrists rattle and your head bangs and you make the same little choking sound you always do. I don’t have Rosemary to help hold you, and if I strap you down now, you’ll stay that way for the entire trip. I try to brace you against the chair, to press my weight against the bucking of your body, hugging you tight as you struggle under me like a trapped animal. You can’t break free. I am so much bigger than you.

Over your shoulder I can see the other fathers and the last of the sons staring at us. We’re ruining the moment they’re collectively trying to have. But what about my moment? Is this the moment they think I wanted? Is this any kind of send-off for a man who has done, if not great things, then at least good things? Things that he didn’t have to do, was not required to do, and yet did anyway, decently and with only minimal complaint? Doesn’t that deserve its own moment? And yet here I am. This is all I can do.

You stop seizing. I feel something wet on my shoulder. In your fit, you’ve spit up the ice cream. It’s oozing down your chin in waves of thick pink, dribbling onto your shirt and pants. I don’t carry a handkerchief. Rosemary usually keeps Kleenex in her purse. I take Avery’s drawing off the tray and use it to wipe your face and dab at the little pool in your lap. I can’t look you in the eyes. I just dab until the helicopter’s copilot tells me he’s sealing the doors.

Everyone has been moved to an outer perimeter so that the helicopter can take off safely. It isn’t until I see Avery’s face that I realize I’m still holding his crumpled pink puke-stained drawing. He’s already in a fragile state, and this sends him over the edge. He presses his face into Rosemary’s dress so hard and deep there’s no way he can breathe. This is an old tactic he used to great effect when he was smaller, until I asked Rosemary to please stop coddling him, because it was plainly making him weak, and although I didn’t want a repeat of Ernest, I also didn’t want a son who suffocated himself in his mother’s skirts. But now she picks him up right away, staring at the soggy paper in my hand like it’s a bloody stump.

This is the last thing we need right now. We should be gathering around one another as a family, relying on our shared love and support to light a path out of this parking lot and back to the happy lives we’ve worked so hard for. Instead, we’re a good three feet from one another, except for Avery, who’s reburied himself in Rosemary’s left breast, gagging on his own tears and shuddering in that baby-mouse way he does. She hands me his balloon like she wants me to go murder myself with it.

“We’ll wait in the car,” she says, which strikes me as a big mistake. Yes, the drawing thing was also a mistake, but this is so much more important in ways I know Rosemary doesn’t see. This could do real, lasting damage to our son.

“If he doesn’t see it take off,” I say, loud enough so Avery can hear over his muffled caterwauling and the slow build of the helicopter’s engines, “he might regret it later.”

Rosemary covers his exposed ear with her free hand and says, “What the hell do you expect me to do?”

“I just don’t want him to regret not doing the right thing when he had the chance,” I say, almost shouting now so that he can hear me through her hand.

She resituates Avery on her hip and carries him away as the helicopter separates from the asphalt.

I still have Ernest. I put my hand on his shoulder as the whirring blades make small cyclones of gravel and trash. Everyone shields their eyes, except for you and the others facing us through the glass. The pilot has a practiced hand. The crate lifts slowly as the cables go taut, with only a slight, cradling rock. Once it’s high enough, we all release our balloons. Ernest lets go of his, and I let go of Avery’s, hoping he’s watching from the car as they become a distant color in a far-off sky. Ernest waves to the crate as it rises. We cannot take our eyes off it, but still, I know he and I are looking at two different things. Where I see a crate carrying my father away, and someday me if I’m lucky, Ernest sees only the resettling of dust, the spinning of rotors, and the might of engines bearing the weight of what is necessary.

I’m not sure what to do, Dad. It’s all I can think standing here with Ernest, watching you go. I surprise myself by saying it out loud.

“I’m not sure what to do.”

It comes out like a cry, the roaring of the helicopter still knocking around inside my ears.

“Just wave, Dad,” Ernest says, as though it were the easiest thing in the world. And so I do. And it is easy.

In a few minutes, after the crate shrinks to the size of a punctuation mark, I will uncrumple Avery’s ruined drawing and reexamine it. I will notice for the first time his great care in rendering the starfish, which is perfectly symmetrical along every axis. I will recognize the gas nozzles, which I suppose he must have learned about in school, already emitting the pencil-thin puffs that will make the groaning and buckling of the crate’s hull easier for you to accept. Looking closer, I will realize that there actually is a dolphin in the picture after all. Its blue body is difficult to make out at first against the blue water, but once I have the outline of it—the crisp salute of its dorsal fin, the slender scoop of its fluke—it will be impossible not to see. The grandfather in the crate gazes intrepidly forward, and the space-suited grandson is so happy, so unafraid. I will study this drawing often in the weeks to come, meditating on its many perfections. I will feel sorry that I am the one looking at it, that it is here with me and not with you, rolled out before you on your tray as the floodlights show you dolphins and marlins, sea breams and hammerheads, and all the other guardians of the undisclosed location, whose waters, we are told, are calm, and patient, and deeper than we can know

__________________________________

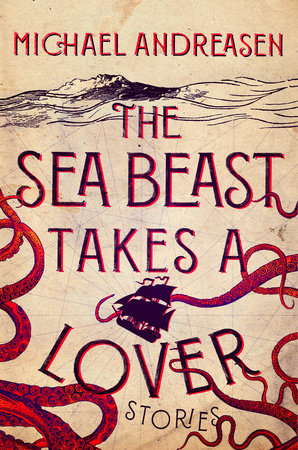

From The Sea Beast Takes a Lover.“Our Fathers at Sea” originally appeared in Zoetrope: All Story. Used with permission of Dutton. Copyright © 2018 by Michael Andreasen.