It’s summer up here by the sea; the gaily colored bathing huts glow in the sun. Stefan Zweig is sitting in a loggia on the fourth floor of a white house that faces onto the broad boulevard of Ostend, looking at the water. It’s one of his recurrent dreams, being here, writing, gazing out into the emptiness, into summer itself. Right above him, on the next floor up, is his secretary Lotte Altmann, who is also his lover; she’ll be coming down in a moment, bringing the typewriter, and he’ll dictate his Legend to her, returning repeatedly to the same sticking point, the place from which he cannot find a way forward. That’s how it’s been for some weeks now.

Perhaps Joseph Roth will have some advice. His old friend, whom he’s going to meet later in the bistro, as he does every afternoon this summer. Or one of the others, one of the detractors, one of the fighters, one of the cynics, one of the drinkers, one of the blowhards, one of the silent onlookers. One of the group that sits downstairs on the boulevard of Ostend, waiting for the moment when they can go back to their homeland. Racking their brains over what they can do to change the world’s trajectory so that they can go home to the country they came from, so that in turn they can maybe even come back here on a visit one day. To this holiday beach. As guests. For now, they’re refugees in vacation-land. The apparently ever-cheerful Hermann Kesten, the preacher Egon Erwin Kisch, the bear Willi Muenzenberg, champagne queen Irmgard Keun, the great swimmer Ernst Toller, the strategist Arthur Koestler: friends, foes, storytellers thrown together here overlooking the sand in July by the vagaries of world politics. And the stories they tell will be the fragments shored against their ruin.

Stefan Zweig in the summer of 1936. He looks at the sea through the large window and thinks with a mixture of pity, reticence, and pleasure about the group of displaced men and women he will be joining again shortly. Until a few years ago, his life had been a simple, greatly admired, and greatly envied ascent. Now he’s afraid, he feels himself bound by a hundred obligations, a hundred invisible fetters. Nothing will loosen them, nothing will provide support. But there is this summer, in which everything is supposed to change. Here, on this extravagantly wide boulevard with its magnificent white house and its great casino, the extraordinary Palace of Luck. Holiday mood, lively atmosphere, ice creams, parasols, lethargy, wind, wooden booths.

* * * *

He was here once before; it was the summer of 1914, when the disaster began; with the headlines and the newsboys all along the beach promenade screaming more excitedly with every day that passed, excitedly and joyously because they were doing the best business they’d ever had.

The majority of the bathers who tore the papers out of their hands were German. The boys yelled the headlines: “Russia Provokes Austria,” “Germany Prepares to Mobilize.” And Zweig too — pale, well-dressed, with wire-rimmed glasses — came down by tram to be closer to the unfolding news. He was electrified by the headlines; they made him feel delightfully aroused and excited. Of course he knew that the whole drama would subside into a general silence soon enough, but right now he simply wanted to savor it. The possibility of a great event. The possibility of a war. The possibility of a grand future, of an entire world in motion. His joy was especially great when he looked into the faces of his Belgian friends. They had turned pale in the course of these last days. They were unprepared to join the game, and seemed to be taking the whole thing very seriously. Stefan Zweig laughed. He laughed over the pathetic troops of Belgian soldiers on the promenade. Laughed over a little dog that was dragging a machine pistol along behind it. Laughed over the entire holy solemnity of his friends.

He knew they had nothing to fear. He knew that Belgium as a country was neutral, he knew that Germany and Austria would never overrun a neutral country. “You can hang me from this lamppost if the Germans march in here,” he cried to his friends. They remained skeptical, and their faces turned grimmer as the days went by.

Where had his Belgium gone so suddenly? The land of vitality, of strength, of energy, and the intensity of another kind of life. That was what he so loved about this country and this sea. And why he so admired the country’s greatest poet.

Émile Verhaeren had been the first spiritual love of Zweig’s life. As a young man, he’d found in him his first object of unconditional admiration. Verhaeren’s poems shook Stefan Zweig to the very marrow as nothing had done before. Verhaeren’s was the style against which he honed his own, first imitating it, then making his own free renderings, then translating Verhaeren’s work into German, poem by poem. He was the one who had made Émile Verhaeren a name in Germany and Austria, and published an effusive appreciation in book form at Insel Verlag in 1913. In it he wrote, “And thus it is time today to speak of Émile Verhaeren, the greatest and indeed perhaps the only Modernist to have absorbed the conscious feeling of contemporary life in poetic terms and bodied it forth, the first to have fixed our era in permanent poetic form with incomparable inspiration and incomparable artistry.”

It was also as a result of Verhaeren’s inspiration, his joy in life itself, and his trust in the world that Stefan Zweig had traveled to Belgium at the end of June, and to the sea. To strengthen the inspiration he drew from Verhaeren’s own inspiration. And to see the man whose poetry he had rendered into German. As, for example, Fervor, which begins:

If we truly admire one another

From the very depths of our ardor and our faith,

You the thinkers, you the scholars, you the apostles

You will draw on us to shape the laws that govern this new world.

They are hymns to life, dream landscapes. Long, clear gazes at the world until it gives off its own illumination and corresponds to the poem that lauds it. And this love of the world, this enthusiasm were both hard-won. Laboriously wrested from a dark reality.

I love my fevered eyes, my brain, my nerves

The blood that feeds my heart, the heart that feeds my body;

I love mankind and the world, I adore the force

That my forces marshal and receive from man and universe

For life’s meaning is: Receive and Squander.

My peers are those who exult as I do,

avid, panting in the presence of life’s intensity and the red fires of its wisdom

Two untamed creatures from the wilds of yearning had encountered one another. Émile Verhaeren and Stefan Zweig. The young Austrian was enraptured by his conversations with his effusive master.

The assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne had not made him change his plans at all. His secure world seemed secure for all time. Stefan Zweig had experienced more than one crisis, and this one was no different from all the others. It would pass, and leave no trace. Like everything in his life thus far.

They were actually due to meet on August 2nd, but then they crossed paths before that anyway, quite by chance, when Zweig was sitting for the painter Constant Montald in his studio in Brussels, and Verhaeren happened to drop by. They greeted each other and talked with their customary warmth. Zweig’s outpouring of enthusiasm struck the bearded Belgian as a little disturbing, but he put up with it. They wanted to see each other again soon and to plunge into discussions about everything imaginable, new poems, new plays, about love too, and new women. Zweig’s theme.

But before this, given the young Austrian’s excitement, Verhaeren had a proposal: could Zweig meet a friend of his up there in Ostend? A rather strange friend, Verhaeren had to admit. Happy to have himself photographed playing the flute on the roofs of his hometown, a painter too, also made masks and drew caricatures, none too successfully up till now, actually not successful at all. His first exhibition was held in a friend’s carpet shop. Once a year he organized a masked ball and ran all around the town with his friends in full costume. Called it “the Dead Rats’ Ball.” More people came every year. This man was called James Ensor. Verhaeren gave Zweig the address and a letter of introduction.

And Zweig went. To the shop owned by Ensor’s mother, right behind the promenade along the beach. She sold carnival masks and shells and paintings by sailors and dried starfish. A narrow house with big display windows at street level, which showed off the exotic offerings hanging from transparent threads. Zweig went in. Yes, he was told, her son was upstairs, why didn’t he just go up. A dark, narrow hallway and stairs carpeted in red, maliciously smirking masks lining the stairwell. He passed a tiny kitchen, red-enameled pots on the stove, dripping faucet. Up on the third floor a man wearing a flat cap was sitting at the piano playing quietly to himself, apparently oblivious to everything around him. On the wall behind the piano hung an enormous painting; hundreds of people in the strangest masks crowded the canvas, struggling toward some unidentifiable destination. Their artificial faces were in an array of garish colors, with long noses and empty eyes. A ball for the dead, a mortal folk festival, a communal frenzy. Zweig stared mesmerized. This was not his Belgium. This was the home of death, this was where he was celebrated. A round table displayed a large armful of dusty grasses in a vase, painted, Chinese, acting as the base for a laughing, toothless skull, wearing a woman’s hat stuck with dried flowers. The man at the piano kept playing to himself and humming. Stefan Zweig stood for a while as if paralyzed, then he turned around and ran down the stairs, through the shell shop and onto the street, in the sun, back into the daylight. He wanted to get away from here, back to being carefree, have something to eat, regain his composure.

He hurried to his companion. Her name was Marcelle and she had accompanied him here. A fantastic woman. Not marriage material, heavens no, more a novelistic thing. A story one could write up later. A sudden, unexpected intensity in one’s life, a plunge, an upwards leap. A stunning eruption of passion. A Stefan Zweig story. Lived out, in order to be described.

His first love, Friderike von Winternitz, had stayed at home in Austria. She made no claims on him, nor could she, because she was married to someone else. And so she wrote to Zweig in Ostend to say he should enjoy himself with his little girlfriend. And enjoy the summer. The glorious summer of 1914, to which Stefan Zweig will always think back in later years, when he utters the word “summer.” The two women, the sun, the sea, the kites in the air, holidaying bathers from all around the world, the great poet, a beach slowly emptying of people.

* * * *

The German visitors were the first to leave the country, followed by the English. Zweig stayed on. His excitement grew. On the 28th of July Austria declared war on Serbia, and troops were marshaled on the border with Russia. Now even Stefan Zweig was slowly obliged to realize that things could turn serious. He bought himself a ticket for the Ostend-Express on the 30th of July. It was the last train to leave Belgium for Germany that summer.

Every carriage was jammed, people were standing in the corridors. Everyone had a different rumor to recount, and every rumor was believed. When the train was approaching the German border and suddenly stopped in open country, and Stefan Zweig saw huge trucks coming toward them, all covered with tarpaulins, and thought he recognized the shapes of cannons underneath, it gradually dawned on him where this train was headed. It was headed into war, which now was ineluctable

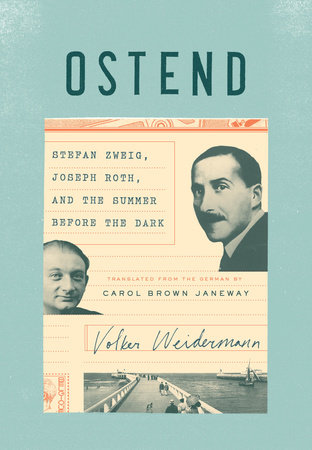

From OSTEND. Used with permission of Pantheon. Copyright 2016 by Volker Weidermann. Translation Copyright 2016 by Carol Janeway.