“I remember you,” Gen told Emily after their first track practice. The October air was cold, the grass brown, but Emily’s face was hot and her breath fast. Running with Gen had been like keeping pace with a streaking deer. Emily was thirsty and annoyed and her body felt like a hot water bottle.

Emily remembered her, too, from elementary school, but Gen’s openness, her light smile—as if practice had been a pleasure and so was Emily’s company—made her pretend that she didn’t. “I don’t think so,” Emily said. “You’re a junior.” A full grade behind Emily. They had been in the same year in fifth grade, but something must have happened after they went to different middle schools.

“Yeah, but I’ve decided I’ll graduate this year.”

“You can’t just decide that.” The other girls on the team had gone ahead of them to the gym entrance. Emily watched the heavy doors slam shut. A raven picked its way through tough grass. Emily made her tired legs move more quickly, eager for the conversation to be over, but Gen lengthened her stride.

“I want to be Class of ’96. I don’t mind extra work.” Gen was stupidly tall and although her shoes were falling apart, her relaxed, graceful pace made Emily think of paintings of gentlemen from bygone eras, the kind on paperbacks like The Age of Innocence. “Are you always this way? Do you not like me, or do you not like someone being better than you?”

The words—said with no resentment, only curiosity—brought Emily to an abrupt halt.

“At this one thing,” Gen amended, her smile still friendly. “It’s just running. It’s not everything.”

“I don’t remember you being this chatty.”

“So you do remember.”

Emily felt embarrassed. Gen was right: Emily was angry because she had been bested. She had tried as hard as she could to run fast and even though she didn’t usually care much about track, there had been something gallingly elegant about Gen’s swiftness, the way it had made Emily feel leaden, earthbound. Although before Emily had pretended not to know Gen because she had wanted to end the conversation, now she didn’t want to talk about how they once did know each other, as little kids, because she worried, suddenly, that she might shame Gen by discussing the circumstances…even though that was clearly what Gen wanted to discuss.

Gen said, “I used to be shy.”

In fifth grade, the new girl who had arrived mid-year wasn’t in Emily’s class but was in her lunch period. Genny Hall had sharp elbows, long legs, and bony knees. Her lunch tray was bare except for a blue carton of skim milk. She opened it and drank so quickly that Emily thought that the girl might throw up.

Emily sat next to Meredith, who had Lunchables and a Hostess cupcake in her My Little Pony lunch box. Meredith ate the cupcake like the commercial instructed: first, the icing, then the cake, then the creamy middle that she squashed with her tongue. Emily didn’t have a lunchbox but always decorated a brown bag before school, writing in painstaking cursive so that it would look adult: Have a Great Day, Emily! Her mother had decorated the bag like that for the first day of school but hadn’t since. Inside was a peanut butter sandwich, which Emily made every day because she didn’t know how to make anything else. She cut off the crusts and told her friends that she was obsessed with peanut butter, it was her favorite.

Kim could do fishtails and braided one into Meredith’s hair. She clipped the bangs back with a butterfly barrette. “Fuh-reak,” Kim said. Emily, for a moment, thought that Kim meant her and worriedly glanced down at the sandwich in her hands, but Kim meant the new girl, who had ripped open the milk carton and was licking the waxed inside.

That night, at home, Emily leaned against the fake wood paneling of the family room, torn between savoring the last few pages of her library book and consuming them. She thought of the girl licking the inside of the milk carton. Emily turned the pages more slowly. The end came anyway. She closed the book and looked at the ceiling, trying not to blink.

“What’s wrong?” Her mother poured Sweet N’ Low into her coffee. “What have you got to cry about?”

Emily glanced down at the book cover with its illustration of a Pegasus. She rubbed the wetness from the cover’s plastic encasing.

“Oh, Em.” Her mother sighed.

Emily wondered if the school library would fine her if she kept the book and claimed it had been lost. Maybe they didn’t fine children. Maybe she could keep it for free, forever. “I know it’s dumb. I know a Pegasus isn’t real but I wish it was.”

“You’re right,” her mother said. “That’s pretty dumb.” She wiped Emily’s cheek and told her to turn on the TV. They adjusted the antenna. CBS came through nice and clear. There were cartoons. Emily’s mother put an arm around her and fell asleep on the couch. When a commercial came on, one Emily knew well, about an old car that was still worth money, she thought about how skim milk was five cents cheaper than whole.

The next day at lunch, Meredith complained about their teacher, who had made them plant grass seeds in Styrofoam cups. The entire class was insulted. “That is so kindergarten,” Meredith said at lunch. “We are not babies.”

“Yeah, fuck photosynthesis,” Kim said, delighted by her daring. The other two laughed to please her. At a nearby table, empty save for her, Genny looked up from her torn-open milk carton. Emily said that she agreed with Kim. “Grass is boring. I like flowers.”

“Gennifer Hall is staring, oh my God,” said Meredith. Emily felt the prickle of the girl’s gaze.

At library hour, Emily went to the history section and found Genny Hall hidden between the stacks, just as Emily had seen her hide earlier that week. Emily thrust a baggie with a peanut butter sandwich at her. That morning, Emily had made two. Silently, gaze down, Genny took the sandwich.

Every day they had library together, Genny accepted a sandwich. At lunch, she drank her milk like a normal person and some days didn’t buy it. Some weeks later, when the cold meant business and snowy boots squeaked down the orange halls, Emily put her hands in her coat pockets at dismissal, looking for her mittens. Something small, flat, and rectangular fell from her pocket to the ground.

It was a packet of marigold seeds. The price was printed on the top right corner. Emily did the math. Six days of skipped milk could buy a packet of marigold seeds.

On the track field beneath the dimming sky, Emily studied Gen, who still seemed underfed—not so much in her body, though Gen was lanky, her features angular, but in the way she looked at Emily expectantly, large eyes dark and growing darker, because even though it was only four o’clock, this was autumn in Ohio and soon it would be dusk. Despite how hot Emily had been after practice, sweat had chilled on her skin. The wind picked up, juggling a tree’s yellow leaves. She shivered.

“You’re cold,” Gen said. “Let’s go inside.”

The attentiveness surprised Emily. It made her wonder what else Gen noticed, what else she was thinking. When they reached the gym doors, Gen said, “Where did you plant the seeds?”

“I didn’t.”

“Oh.”

“I liked them too much,” Emily said in a rush. “If I planted them, they’d grow but then they’d die. I liked imagining what they’d look like better than seeing what they did look like.” She still had the packet. It was in her desk drawer at home, mixed in with birthday cards from her father.

“That’s nice,” Gen said.

“It is?”

“Yeah. Save them for when you need them.”

“Okay.”

“Do you want to go running together?”

“At practice?”

“Just us.”

That was October. In June, Emily’s legs were tangled between Gen’s in the flatbed of Gen’s pick-up truck, the metal hot beneath her skin. Summer slid into September and Emily was moving into her double in Thayer Hall at Harvard. Emily’s roommate, brash and lively, ordered pizza and asked questions that were inappropriate yet endearing, because they were predicated on the assumption that they were already friends. “Let’s get the basics out of the way,” Florencia said. “How many guys have you slept with?” When Emily said none, Florencia shrieked, “You’re a virgin?”

“I didn’t say that.”

Florencia wanted every delicious detail.

__________________________________

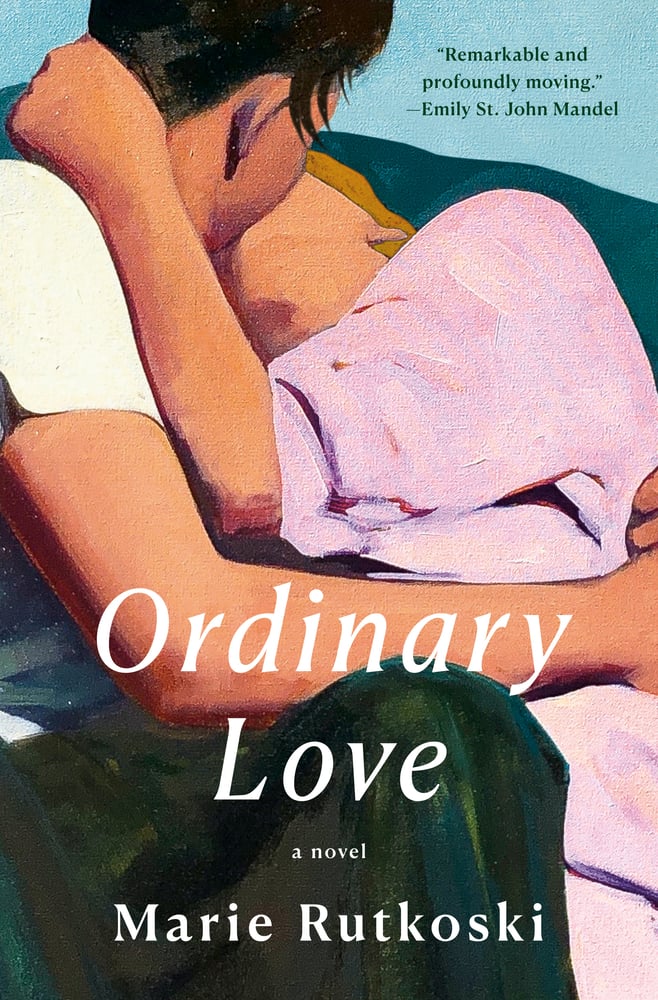

From Ordinary Love by Marie Rutkoski. Used with permission of the publisher, Knopf. Copyright © 2025 by Marie Rutkoski.