“One of the Greatest in United States History”: On the Friendship Between Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge

Laurence Jurdem Explores the Relationship Between Two True Believers in American Exceptionalism

“[Lodge] was my closest friend personally, politically and in every other way and occupied toward me a relationship that no other man has occupied or will occupy.” —Theodore Roosevelt on Henry Cabot Lodge June 20, 1900, Philadelphia

The entertainment began at eleven o’clock in the morning with a tribute to the music of John Philip Sousa by the Municipal Band of Philadelphia. As the melody echoed through Exposition Auditorium, those who gathered to celebrate the 1900 Republican National Convention eagerly anticipated a memorable afternoon. By the time the Rev. Charles M. Boswell delivered the invocation signifying the opening of the second day’s festivities, it was just after 12:30, and few of the 15,000 spectators awaiting the nomination of William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt for president and vice president of the United States chose to stand. To Boswell’s dismay, the delegates seemed to have little taste for religion.

Moments after Boswell left the stage, a procession of fifteen elderly men gathered at the rear of the arena. As “the white-haired patriarchs” proceeded toward the speaker’s platform, they carried with them a faded version of the Stars and Stripes. Led by seventy-three-year-old Senator Joseph Hawley of Connecticut, the group symbolized the last remnants of the delegation to the first Republican National Convention, held in Philadelphia forty-four years earlier.

As Hawley and his colleagues stepped to the platform, an enormous roar shook the arena. Gazing out upon the gallery of cheering spectators, the members of that distinguished company who cast their votes more than four decades earlier in favor of the legendary explorer and politician, John C. Frémont, swore their devotion to the vision and values of the Republican Party.

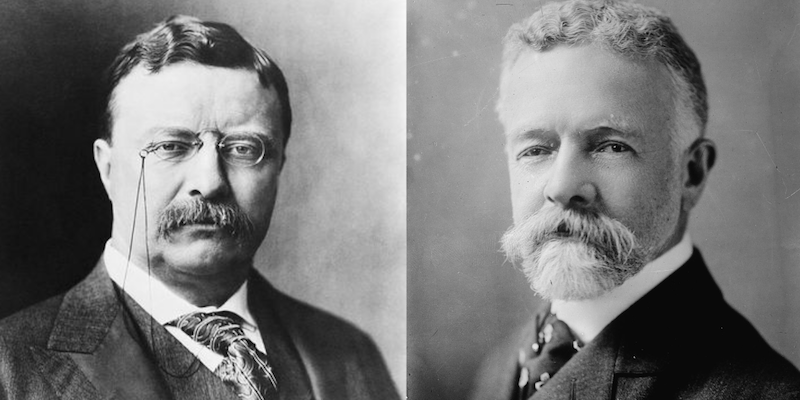

As the ovation continued, the person applauding with the most enthusiasm may have been Theodore Roosevelt. Known for his near obsession with physical activity, the forty-two-year-old governor of New York maintained his conditioning through a regimen of boxing, rowing, and weightlifting. At five foot nine, two hundred and fifty pounds, with a thick neck, barrel chest, and a bushy mustache barely concealing his large white teeth, Roosevelt’s spectacle-covered eyes rigorously scanned the building, never wanting to miss a moment of excitement.

A figure with a wide smile and contagious laugh, Roosevelt possessed the ability to be comfortable with people from any walk of life. A natural raconteur, the governor delighted friends and acquaintances with endless stories of his adventures in Cuba during the SpanishAmerican War or his early days as a rancher in the Badlands of the Dakota Territory. Possessing enormous physical energy and a magnetic personality, Roosevelt enjoyed virtually every task he undertook. Whether enthusiastically smacking supporters on the back while campaigning for office, speaking expansively about the three books he read that day or simply wrestling with his children, many considered Theodore Roosevelt a sheer force of nature.

Born into an elite New York family in 1858, Roosevelt grew up admiring the GOP’s most famous standard-bearer, Abraham Lincoln. The man known to his admirers as “the Great Emancipator,” believed all individuals regardless of race, color, or creed should have the opportunity to achieve a piece of the American Dream. The governor also shared Lincoln’s positions on issues like property rights and the necessity for a protective tariff. Diverging from his political hero on the issue of immigration, Roosevelt believed restrictions were necessary to preserve the economic livelihood of his fellow citizens.

The governor understood his role in the upcoming campaign required praising McKinley’s tenure as president, while simultaneously attacking the populism of the likely Democratic challenger, William Jennings Bryan. “The Hero of San Juan Hill” opposed Bryan’s economic radicalism. But Roosevelt also remained concerned with the nation’s growing economic disparity.

As members of the New York delegation celebrated the party platform of low taxes and limited corporate regulation, more than three-quarters of their fellow citizens lived on the margins of society. The former “Rough Rider” contended these positions were detrimental to the concept of fair play. It was not enough to simply embrace the corporate titans of the new industrial era. The leadership of the GOP needed to advocate for policies that once again welcomed those willing to strive, take risks, and engage in what Roosevelt referred to as “the strenuous life.”

Throughout their careers in public life, Lodge and Roosevelt encouraged one another to mine the greatness that resided within each of them.A short distance away sat Roosevelt’s dearest friend, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts. An imposing and intimidating man at six foot two, Lodge, stoic and cerebral, maintained his slim, athletic frame through fox hunting, tennis, and frequent rides with Roosevelt through Washington, DC’s Rock Creek Park. Renowned for his natty style of dress, Lodge’s “finely chiseled features, [hazel] eyes,” and “closely cropped iron gray beard” gave the Bay State Republican every inch the image of elegance and dignity.

A skilled debater and superb parliamentarian, Lodge, born in 1850 and descended from one of the premier families in Massachusetts, exhibited little humor or warmth. When, however, he was in the presence of his vivacious wife, Anna Cabot Mills Davis Lodge, known affectionately as “Nannie,” intimate friends like Roosevelt, his elegant but overprotective wife Edith, or the engaging British diplomat Cecil Spring Rice, Lodge was an engaging conversationalist known for quoting Shakespeare and other forms of literature.

Possessing strong personal loyalty, professional integrity, and moral character, Lodge also had an unpredictable temperament which could erupt at any moment. When one of his own constituents accused the senator of moral cowardice, Lodge, despite being in his middle sixties, punched the man in the face.

Throughout their careers in public life, Lodge and Roosevelt encouraged one another to mine the greatness that resided within each of them. In that regard, the New York patrician looked forward to hearing Lodge address the delegates in his role as permanent chairman of the convention. A staunch party man, who believed the only good Democrat was a “politically dead one,” the senator’s remarks were expected to highlight the accomplishments of President McKinley and his administration over the last four years.

Concerned with the rapid “consolidation of industry” Roosevelt and Lodge each contended that those like McKinley and his premier adviser, Senator Mark Hanna of Ohio, were too sympathetic to the interests of American business. The 1900 presidential nominee and his colleagues favored policies that allowed financial speculation to flourish. Roosevelt and Lodge believed that the only way all Americans could thrive economically was through the application of government power to constrain the financial inequalities they believed responsible for the country’s social instability and moral decay.

Known as one of the most erudite men in the nation’s capital, many admired Lodge’s intelligence and devotion to duty. But Lodge was no orator. In fact, the former Harvard professor’s speaking style was so tedious someone once “compared it to the tearing of a bed sheet.” Roosevelt, however, eagerly anticipated Lodge’s remarks, describing him to a friend as one who possessed not only a “delightful, big-boyish personage,” but someone he admired with reverence and respect.

As the applause honoring Hawley and his colleagues subsided, Senator Edward Wolcott of Colorado, the convention’s temporary chairman, announced that Roosevelt would be part of a small committee selected to escort Lodge to the forefront of the arena. A popular figure on the Washington social scene, with a taste for faro and other games of chance, Wolcott was an ardent supporter of the party’s vice-presidential nominee.

Roosevelt, dressed in a dark suit and trademark Rough Rider hat, always enjoyed being at the center of attention. The Washington Post noted, however, that despite the strong ovation, the governor of New York “made no effort to conceal the annoyance he felt at thus being dragged into view.” That expression of irritability was due to Roosevelt’s conflicting emotions over his decision to serve as McKinley’s running mate, an issue he had struggled with from the moment Lodge first raised the idea in the summer of 1899.

Following Wolcott’s introduction, Roosevelt, accompanied by Governor Leslie Shaw of Iowa, guided Lodge to the convention platform. The senator, who stood ramrod straight and whose voice “showed splendid carrying power,” praised the achievements of the current occupant of the White House, for “promises kept” and “work done.” Throughout the address, as applause interrupted Lodge’s remarks, Roosevelt could not help but realize how far the two men had come in their personal and professional lives.

In 1884 Roosevelt and Lodge faced political ostracism following their failed effort to topple the nomination of GOP presidential candidate James G. Blaine. Out of that experience, the two forged a friendship of more than thirty years that in time proved responsible for changing the course of the history of the United States. That relationship not only accelerated the rise of Theodore Roosevelt but played a significant part in the nation gaining a prominent position in world affairs.

Proponents of American exceptionalism, Roosevelt and Lodge believed the ideas encapsulated in the Declaration of Independence of 1776 and the Constitution of 1787 represented something entirely unique in human history. The two politicians contended the country could only achieve its destiny by achieving its rightful place on the international stage. In 1898, Lodge and Roosevelt waged a strategic campaign to acquire key territories in the Pacific theater. Both men believed these expansionist objectives not only enhanced the country’s national interests but provided a means of invigorating the nation’s character during a period of drift and division.

On more than one occasion, the friendship between the two came under strain. Following Roosevelt’s succession to the presidency in 1901, Lodge, always the more successful of the two, suddenly saw his protégé at the top of the political pyramid. Despite the sudden shift in their relationship, Lodge’s admiration for Roosevelt never wavered. But during Roosevelt’s tenure in the White House, his desire to ideologically expand the Republican Party caused the president to embrace a series of progressive reforms contrary to his mentor’s conservative point of view.

In 1912, the tensions between the two exploded for all to see. With the objective of securing a third presidential term, Roosevelt bolted from the Republican Party in favor of a populist agenda. That path, one that Lodge had warned Roosevelt never to choose, created serious differences between the two men. The senator believed Roosevelt’s support of positions like the recall of judges and the direct election of senators not only endangered the fortunes of the Republican Party but threatened the foundations of the nation’s democratic system.

Following the defeat of Roosevelt’s independent drive for the presidency, the two men reunited over their mutual disdain for the personality and policies of Woodrow Wilson. Both believed Wilson’s foolish idealism and weak character placed the greatness of the United States in jeopardy. The relationship between Lodge and Roosevelt endured many twists and turns, including the tragic deaths of friends and family. Despite these traumatic moments, the personal conviviality between Roosevelt and Lodge continued until the former president took his final breath in January 1919.

Theodore Roosevelt viewed Henry Cabot Lodge as “his closest friend, personally, politically and in every other way.” Lodge, in turn, believed Roosevelt to be “one of the most loveable as well as one of the cleverest and most darling men I have ever known.” The two men “complemented each other perfectly.” They shared an interest in sports, history, literature, and living well. Most important, they possessed a common vision of the United States as a force for good in the world. Along with their wives, they were as close as any two people could be.

While the two men occasionally differed in their political views, their upbringing and education were almost identical. Having each lost fathers, at the ages of eleven and nineteen respectively, neither Lodge nor Roosevelt had a strong role model to ground or guide them as they reached adulthood. Raised with a much older sister and doted on by his mother Anna, Lodge developed a wide array of acquaintances but very few friends. While many of Lodge’s contemporaries enjoyed glamorous evenings or summers in Newport, Rhode Island, the senator preferred reading or writing in the isolated beauty of his family home overlooking the sea on the Eastern shore of Massachusetts.

It is no surprise numerous historians describe the friendship between Roosevelt and Lodge as “one of the greatest in United States history.”Roosevelt, ill for much of his childhood, also spent considerable time alone. Surrounded by books on history, literature, and the natural world, Roosevelt had little connection with other children except for his three siblings. Once close with his brother Elliott, the two siblings slowly drifted apart as the younger Roosevelt succumbed to mental illness, exacerbated by a long struggle with alcoholism. While T. R. adored the company of people, the two-term president had few he relied on for consistent advice and counsel.

Over time Lodge became Roosevelt’s confidant, the only person other than his wife and two sisters with whom he believed he could share his deepest thoughts or feelings. In a friendship of more than thirty years, each treated the other as a member of their extended family. It was a relationship Roosevelt grew to value. “[Y]ou two are really the only people for whom I genuinely care,” Theodore confessed to Nannie Lodge in 1886.

Without question, Roosevelt’s tremendous personal gifts would one day have made him a contender for the presidency. That sudden surge of upward mobility when Roosevelt rose from state assemblyman to president in just over sixteen years would never have occurred if not for the acumen and connections of Henry Cabot Lodge.

Over the course of their decades-long friendship, the two exchanged more than twenty-five hundred letters, and wrote about one another’s attitudes and activities in correspondence with family and close friends. It is no surprise numerous historians describe the friendship between Roosevelt and Lodge as “one of the greatest in United States history.”

_______________________________

Excerpted from The Rough Rider and the Professor by Laurence Jurdem. Copyright © 2023. Published by Pegasus Books.