One Man's Literary Crusade to Uncensor Sex in America

On Gershon Legman, Original Sex-Positive Hipster Intellectual

In 1948 Gershon and Beverley Legman moved to the Bronx, to 858 Hornaday Place, near the zoo and Grand Concourse. The tiny cottage they had rented was a minor landmark—it had been built by Charles Fort, the early-20th-century naturalist, journalist, and investigator of “anomalous phenomena.” Legman was now at work on his studies of sex censorship, and he started a small weekly gathering. Over stew and cheap wine, he would hold forth. The Thursday evenings became, briefly, a scene to make in bohemia, the visitors and the evenings contributing to the legend of Legman. Novelist John Clellon Holmes and his friend, hipster Jay Landesman, took Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac there. Lionel and Diana Trilling, among other New York intellectuals, braved the long subway ride to the Bronx.

The evenings were modest and outrageous. Beverley and Gershon were famous for scraping by. Clellon Holmes noted, “Legman could fill a shopping bag for 40 cents. . . . [H]is soul took some of its sustenance from the very ingenuity of feeding the two of them.”

Legman’s friend Osmond Beckwith, a poet and novelist, remembered how cramped the cottage was, with everyone sitting on a bed in the front room. The whole place was “very dusty” and full of Beverley’s cats, “which were not to be picked up or held.” He noticed Beverley’s remoteness, that she “seemed to keep herself under great restraint; spoke and acted without much feeling.” Legman was volcanic, speaking “with the pent up energy of someone who hadn’t met anyone in weeks.” He talked so fast and “made so many references” to his research that Beckwith felt dazed by “the most non-stop talker I’d ever known.”

The library was Legman’s real work. Beckwith eyed Freud’s Collected Works and several important dictionaries with envy. He later told Gershon, “My impression was you had the best, the original references, those I’d heard of but never bought, lacking the money.” When Legman showed him Oragenitalism, Beckwith was taken aback. He had never heard people speak of oral sex positively or even “recommend it.” Legman displayed posters he had had made from comic book covers; he “brought out a book with some homosexual illustrations” that surprised Beckwith more.

John Clellon Holmes was stunned by the contents of Legman’s tiny house. Past the weedy yard and the unpainted fence, he recalled, “the first thing you noticed were books. Books everywhere, books overflowing the shelves on every available wall, books tucked under the desk.” The cottage contained the “carefully assembled literature of a scholar and bibliographer . . . [of] sex and language,” with “dictionaries and lexicons, rare and expensive books,” and editions of Freud running to many volumes, which had been “liberated one book at a time for hard-earned cash.” Hornaday Place was a command post, Clellon Holmes wrote, “and from that overflowing desk a species of war was being carried on with the world that lay just beyond the hand sewn drapes.”

Legman had sent out the usual avalanche of correspondence to publishers and well-known writers who might help his campaign to uncensor sex.

At the back of the cottage, an original bedroom was now the “Filing Cabinet,” Legman’s research warren. Clellon Holmes noted how carefully Legman guarded it: “The precious files that represented over a decade of effort to preserve every evidence of contemporary sex life, and its debasement, had to have a safe, dry room and a door with a lock. This was Legman’s sanctum sanctorum, you were not allowed to linger there.” There were “packing crates where hundreds of comic books were arranged according to degree of atrocity.” “Reams of erotic photos going back to the camera’s earliest years were motif indexed under such headings as ‘Intercourse—Oral—Homosexual’ and ‘Bondage—Masochistic—Female.’” Letters were meticulously filed. Partitions separated the tiny rooms, but finally Clellon Homes saw that “the Work and the Life were indistinguishable.”

The supper conversation was uninhibited and confrontational. Legman would tell about his miserable childhood in Scranton, about the prudery and anti-Semitism, and having had “Kosher” written on his face in horse-shit juice. He described his projects: his encyclopedia of sex techniques, his lexicon to supplement The Oxford English Dictionary, which would contain all the suppressed words. He described his “massive collection of erotic limericks and their variations.”

Legman had a habit of attacking his visitors, and Clellon Holmes got the impression that a lot of people came for just this. In his words, “Legman had a curious effect on people. Frankly, an evening with him could be an ordeal. If you had a secret layer of apathy, compromise or dishonesty, he would instantly sniff out and subject it to a barrage of sarcasms.” Although he treated most women with old-fashioned gallantry, “he nevertheless insisted upon talking about the most intimate matters, in the most pointed obscenities, to all of them.”

Clellon Holmes summarized Legman’s sexual politics: “I have seen him say to a girl he had just met that evening, ‘Anything that fouls up the relations between men and women, I’m against. Starting with your panty girdle, honey. . . . When are you going to give this guy,’ indicating her delighted swain, ‘a chance to prove he’s a man, instead of a god damn tennis player?’” These shocks felt stimulating and liberating, at least to the male dinner guests, because, as Clellon Holmes reflected, “There was an aura of total freedom about him, of honesty without mercy, of having nothing to lose, that made you realize your usual social armor was unnecessary . . . even as he hacked away at it like some psychiatric Genghis Khan.”

The one-sided conversation usually turned to the theory behind the work in progress. Legman told Clellon Holmes (and everyone else) he had discovered that the “increasing violence and sadism of American culture was the direct result of our society’s relentless suppression of sex.” The stand Legman took was unique in those days, summed up in the title of the book he was working on, Love & Death. His book had been rejected “by an entire alphabet of over 30 publishers in America,” before Jay Landesman began to publish parts of it in Neurotica. The loneliness of Legman and his ideas put Clellon Holmes in mind of “St. Jerome of the Bronx,” but his persistence was remarkable. He had sent out the usual avalanche of correspondence to publishers and people who might know publishers and to well-known writers who might help his campaign to uncensor sex. A surprising number replied: he heard back from Upton Sinclair, Wilhelm Reich, and Edmund Wilson. Dwight Macdonald thought the chapter he considered for Politics was interesting but was not quite sure what the point was.

Love & Death: A Study in Censorship was a series of essays on popular culture. Looking back on it, Legman would call his “little hundred-page indictment” his favorite work, a cri de coeur. In fact, it was him “down to the marrow” of his bones, he wrote when he sent a copy to Ewing Baskette, a fellow collector of banned books. Love & Death was an early salvo in what would later be called the mass-culture debates. From the mid-1940s, Legman was increasingly preoccupied with cheap print culture, particularly in the crime novels and comic books that would draw the attention of critical cultural analysts of a later generation. He was not alone in this, but it was an outsider’s enterprise. Caribbean Marxist historian C. L. R. James was at almost the same moment writing about Dick Tracy, albeit in a much different vein. Leo Lowenthal, the Frankfurt School literary scholar, was working on a study of iconic patterns in popular magazines and novels. In Great Britain, first F. R. and Q. D. Leavis, and later Raymond Williams and Richard Hoggart, would develop modes of criticism to take popular reading seriously.

Because popular culture permeated the intellectual life of the nation, Legman made it his ground zero.

But in the late 1940s, this was an outsider’s job. In the context of the early 21st century, after decades of academic and critical attention to the cultures of reading and television viewing, it is hard to re-create the shock that an analysis of cheap print could cause in intellectual circles. Engaging with inexpensive and unsanctioned images and texts, and by extension with the lives of people who created and enjoyed them, was almost unspeakable in the serious literary circles where popular reading was viewed as a subintellectual waste product. There were no university programs, no granting agencies, no journals interested in studying such trash. So Legman invented his own method, collecting comics and pulps from kids in his neighborhood. Osmond Beckwith remembered asking Legman how he did all the research for Love & Death. Gershon replied, “I did it all at the corner candy store.” In a little social welfare project, he sometimes traded less harmful comics to kids for their grotesquely violent ones, but there is no evidence that he interviewed children about their reading habits.

*

Legman’s letters from 1946 to 1949 show him thinking about commercial print culture, including reading material and advertising, in a direct reaction to the catastrophes of World War II and the country’s psychic state as the war ended. In his approach to what was now being called “mass culture,” he was intensely aware that American life was becoming dominated by expanded consumption at home and an aggressive and domineering military stance abroad. Legman registered the newspapers’ triumphal celebration of the American way as the alpha and omega of history with disgust. He berated one correspondent, publisher E. Haldeman-Julius (creator of the “Little Blue Books”), for not taking advertising seriously and for his old-fashioned, freethinking views about religion. As a Marxist, Legman understood the world in terms of exploitation of the poor and weak by the rich and powerful, and he agreed that religion was a gigantic diversion from class struggle. But now capitalism was the new religion, and Haldeman-Julius needed to reckon with this reality. Legman prodded him:

You keep beefing about religion and capitalism in different columns—why can’t you get the idea that they’re one and the same thing? Time was when religion tore the paper when the Rich sat on the toilet over the heads of the working class, but now . . . in the papers the attitude [is] that capitalism is sacred and not to be attacked by logic or satire or anything like that, . . . it is beyond criticism, that nothing is expected of it, that it just is THE THING, and that since the alternative is the outer darkness and Anti-Christ of communism we must clutch capitalism to our bosom no matter how gruesomely (like the Spartan boy’s wolf) it feed on our innards.

An even larger, more sophisticated commercial and ideological system of exploitation was emerging, and the exploitation of ordinary and working people was becoming even more complete via the mass media. As for the relief felt at the end of the war, it was undercut by people’s completely justified fear of a future dominated by atomic mass murder. But Legman wanted to push this critical perspective further: “As to the atom [bomb] the real danger is missed by everyone—it isn’t that they will blow us all to subatomic smithereens without warning it’s that they won’t do it soon enough and we will have to live with this here now world of the future they are preparing!”

“They” were preparing for the citizenry a planet intellectually as well as physically laid waste, all in the name of the glorious American way. Legman saw this manifested in an aggressive postwar rush of new advertising. He was fastidiously collecting the pushy new ads for consumer goods, and he argued from his evidence. “Get hold of a copy of Scientific American—man, it’s appalling. Sky writing that can be lit at night and will burn for 30 minutes, blotting out Cassiopeia with drink grepsi-cola, its the crap for you!! Broadway science which will belch the odor of cooking coffee, frying bacon, last month’s Kotex pads and Secaucus stock farms over the harmless pedestrian! Etc. and omigod.” Here we see Legman’s concrete and vivid polemic style, and while he was being satirical, like many Americans he was really frightened. What appalled Legman was not only that the United States failed to prevent catastrophe in Europe, but also that it celebrated the nuclear murder of hundreds of thousands of people in Japan. And even worse, this horrific violence was becoming seamless with the violence of advertising, a manipulation of minds that in Legman’s view permeated everything.

As he wrote in Love & Death, America, like fascist Germany, seemed to be moving deathward; people took pleasure in mass killing, and this pleasure was efficiently distributed by commercial entertainment. He was writing as the United States heated up the Cold War abroad and laid plans for an open conflict with China in Korea that would devastate and divide that country. At home, dissent was repressed ferociously with political witch hunts and purges. Legman called out that this was the absolute last moment to avoid a planetary descent into sadism. Because popular culture permeated the intellectual life of the nation, Legman made it his ground zero.

Love & Death was made up of linked essays on popular fiction. Legman unpacked detective and crime fiction in “The Institutionalized Lynch” and assailed misogynist depictions of women in mass culture in “Avatars of the Bitch.” A central piece of the book, the chapter people admired the most, was “Not for Children,” a sustained attack on comic books. Here his perspective on kiddie reading was delivered with characteristic heat and force, and he used the psychoanalytic concepts of repression and displacement, albeit in an entirely negative, antimodern critique. Legman’s main argument was that because of the dominant American pattern of sexual repression, cheap fictions offered a kind of distorted expression of human desire. America’s censors allowed stories that dealt in woman hating, racism, violence, and sadism, and they trained a generation of young Americans to enjoy murders, corpses, and the torture of “bitch-goddesses,” at the same time forbidding practical knowledge and the open enjoyment of sexual desire. The result was a perverse national culture dominated by men (most likely homosexual) who hated women. Women sensed that they were hated and thus became “frigid,” and normal men lost their masculinity and became too confused to do anything about it.

————————————————

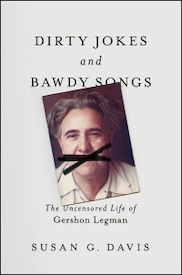

From Dirty Jokes and Bawdy Songs: The Uncensored Life of Gershon Legman by Susan G. Davis. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press. Copyright © 2019 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois.

Susan G. Davis

Susan G. Davis is a professor emerita of Communication and Library and Information Science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She is the author of Parades and Power: Street Theatre in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia and Spectacular Nature: Corporate Culture and the Sea World Experience.